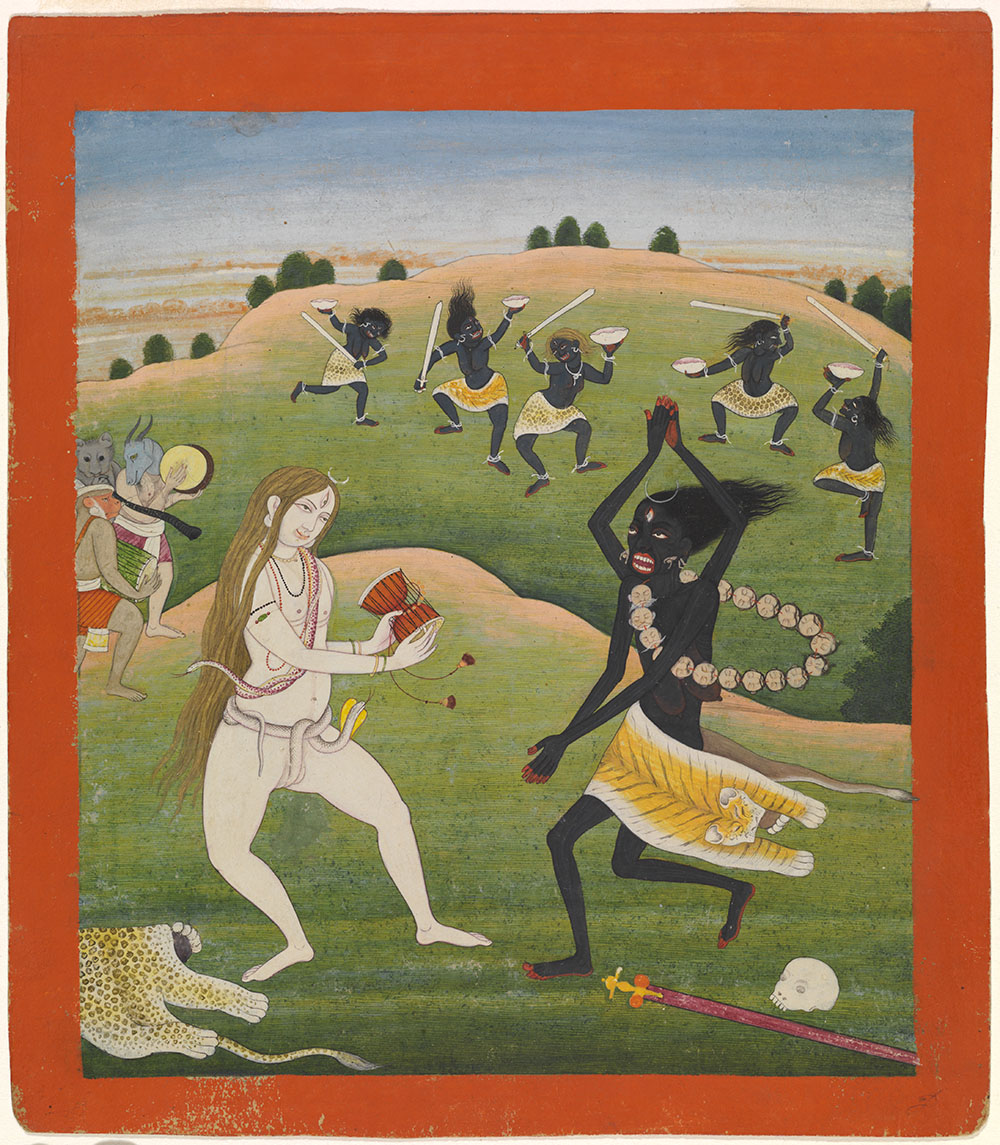

The Dance of Shiva and Kali, circa 1780, India; Punjab Hills, Guler, opaque watercolors and gold on paper, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Adolph D. and Wilkins C. Williams Fund, 82.141

Hello, my name is Kamellia Smith. I am community partner of the Cincinnati Art Museum. I will be reading the Subjugation section of Beyond Bollywood: 2000 Years of Dance in Art.

In Hindu and Buddhist contexts, dance sometimes accompanies—or even brings about—the conquest of negative forces. Deities are shown dancing on corpses personifying death and ignorance, or atop demons who attempt to overthrow order. The Buddhist deity Hevajra steps on four demons that embody evil, his dance transcending their combined power. Shiva slays an elephant demon through dance, releasing the malignant powers that threaten him. Krishna dances atop the serpent demon Kaliya, restoring universal order. And the mother goddesses dance with ecstatic abandon to overpower negative forces. Through dance, the fear of death, impurity, illusion, and ultimately ego-attachment are defeated. These dances are extreme spiritual practices that foster transformation: deities dance to release, to overcome, to remove illusion, and to mark the victory over time and death. By staging rituals in which the dances were evoked or enacted, kings could mobilize supernatural powers to aid in their assertions of hegemony.

Negative forces can also be expressed through dance, often in attempts to seduce and disempower in circumstances where romance and sexuality are potent weapons to overcome. The demon Mara, a personification of evil, sent his daughters to tempt the Buddha as he sat meditating. The demon’s daughters appeared before him as women of different ages and occupations, suiting any taste or fancy. The Buddha’s stoic resistance to temptations of the flesh demonstrates power, strength, and good over evil; to overcome is to transmit such earthly desires into a manifestation of wisdom and knowledge. This, too, can be witnessed through dance.