- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

13 Spooky Artworks for Halloween!

by Charlotte Ogorek, Rexroth Project Assistant with CAM's Curatorial Assistants

10/29/2025

Happy Halloween from your friends at the Cincinnati Art Museum! To celebrate, we’re diving into the deep, dark corners of CAM’s collection of 73,000 objects. Enjoy this selection of artworks chosen by the museum’s curatorial assistants, ranging from the cute and creepy to the ghoulish and ghastly!

And don’t forget to stop by the museum on October 31 from 5–9 p.m. for our Halloween-themed edition of Art After Dark “All Hallows’ Eve”. It’s sure to be a scary (and FREE) good time!

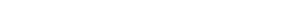

William Verplanck Birney (American, 1858–1909), The Ghost Story, circa 1897–1899, oil on canvas, Gift of The Procter & Gamble Company, 2003.54

In this painting from the 1890s titled The Ghost Story by William Verplanck Birney, a woman brandishes a knife while telling a scary story—and in the process, spills her basket of apples! As her four listeners react with wide eyes and startled expressions, an older woman stirs a large pot in the background; the rising steam gives her an almost ghostly appearance.

Akoda (Pumpkin), 2013, Katsumata Chieko (Japanese, b. 1950), glazed stoneware, Gift of Carol and Jeffrey Horvitz, 2022.150, © Katsumata Chieko

To achieve the weathered, mottled green-and-orange surface of this ceramic work titled Akoda (Pumpkin) by Katsumata Chieko, the artist added layers of colorful slips and fired the work repeatedly. According to Katsumata, each of her pumpkin-shaped works has its own “powerful life force.”

Plate, 1884, Haviland & Co. (French, est. 1842), maker of form, M.M., decorator, porcelain, Gift of Theodore A. Langstroth, 1970.642, photography by Anthony Walsh

In this French porcelain plate from 1884, the artist incorporated images of flying bats, crawling spiders, and branching spiderwebs — all particularly seasonable additions!

Ashtray, circa 1915, Edward Timothy Hurley (American, 1869–1950), bronze, Gift of Theodore A. Langstroth, 1970.634, photography by Rob Deslongchamps

It seems the oversized spider in the center of artist Edward Timothy Hurley’s Ashtray from 1915 has managed to trap a few insects in its intricate web—this piece is ready-made for Halloween!

Kawanabe Kyōsai 暁斎河鍋 (Japanese, 1831–1889), Female Ghost, Meiji period (1868–1912), hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, Gift of the Robert F. Blum Estate, 1906.5

This painting by Kawanabe Kyōsai from Japan's Meiji period (1868–1912) depicts a female ghost or yūrei, a scorned spirit trapped between this world and the next. Often tied with themes of grief and revenge, female ghosts became a popular subject during the Edo period (1615–1868) in not only painting, but also prints, literature, and theater.

Check out this painting now on view in Rediscovered Treasures.

Ernst Ferdinand Oehme (German, 1797–1855), Moonlit Landscape with a Castle, 1853, oil on canvas, The Thomas P. Atkins Fund for European Art, 2024.24

Created by leading Romantic painter Ernst Ferdinand Oehme in 1853, Moonlit Landscape with a Castle depicts a gloomy landscape of trees and marshes with a glistening lake under an eerie night sky. Emerging from the dark tree line, a fictious castle evokes the architecture and natural landscape of Saxony, Germany. Oehme’s synthesis of natural beauty and ghostly darkness craft a sublime image perfectly suited to the Halloween spirit.

Charles François Daubigny (French, 1817–1878), Effet de nuit, 1862, cliché-verre print, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.586

Painter and printmaker Charles François Daubigny created Effet de nuit (Night Effect) in 1862 with a cliché-verre (glass plate) technique used in both photography and printmaking. Here, the artist etched a night scene onto a glass plate then pressed it on light-sensitive paper and exposed it to light. The resulting composition is dominated by shadows and silhouettes; the only source of light is from the moon’s reflection on the water.

Jewelry Ornament, 1780–1820, gold, human hair, composition, seed pearls, glass, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Fleischmann, 2009.309.

Before photography, people created representations of loved ones or “tokens of self” with jewelry incorporating the hair of the deceased. This "hairwork" included visual motifs symbolizing love, affection, remembrance, grief, and mortality. The skeleton imposed on top of the lock of hair in this Jewelry Ornament, which could be attached to a choker or bracelet, was one of the most powerful visual symbols associated with the sentiment momento mori or "remember you must die."

Brooch, 1840s, enamel, gold, glass, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Fleischmann, 2005.85

This Brooch from the 1840s depicts a grave urn with a small window revealing the hairwork of the deceased. The weeping willow was a symbol of the grief of loss but also held another meaning; these trees were known to regrow after their limbs were cut back, symbolizing for the wearer that death was not the end.

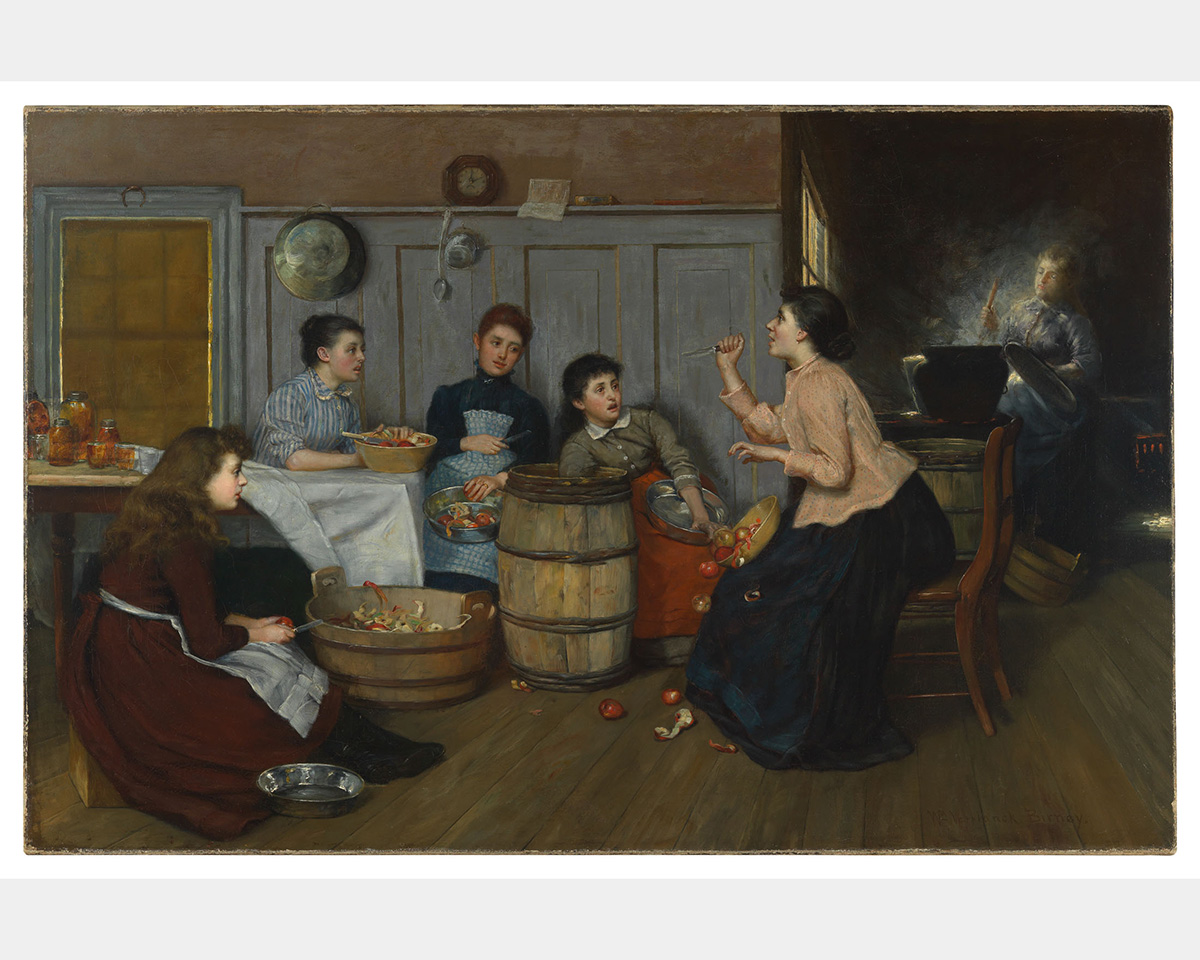

Yinka Shonibare (British, b. 1962), The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia), 2008, C-print mounted on aluminum, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 2012.19

Photographer Yinka Shonibare’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters (Australia) from 2008 is the artist’s take on the iconic print of the same name by Francisco Goya (Spanish, 1746–1828), currently on view in Gallery 211. Shonibare highlights the eerie owls and bats leering over the sleeping man, dressed in a suit made of Ankara fabric.

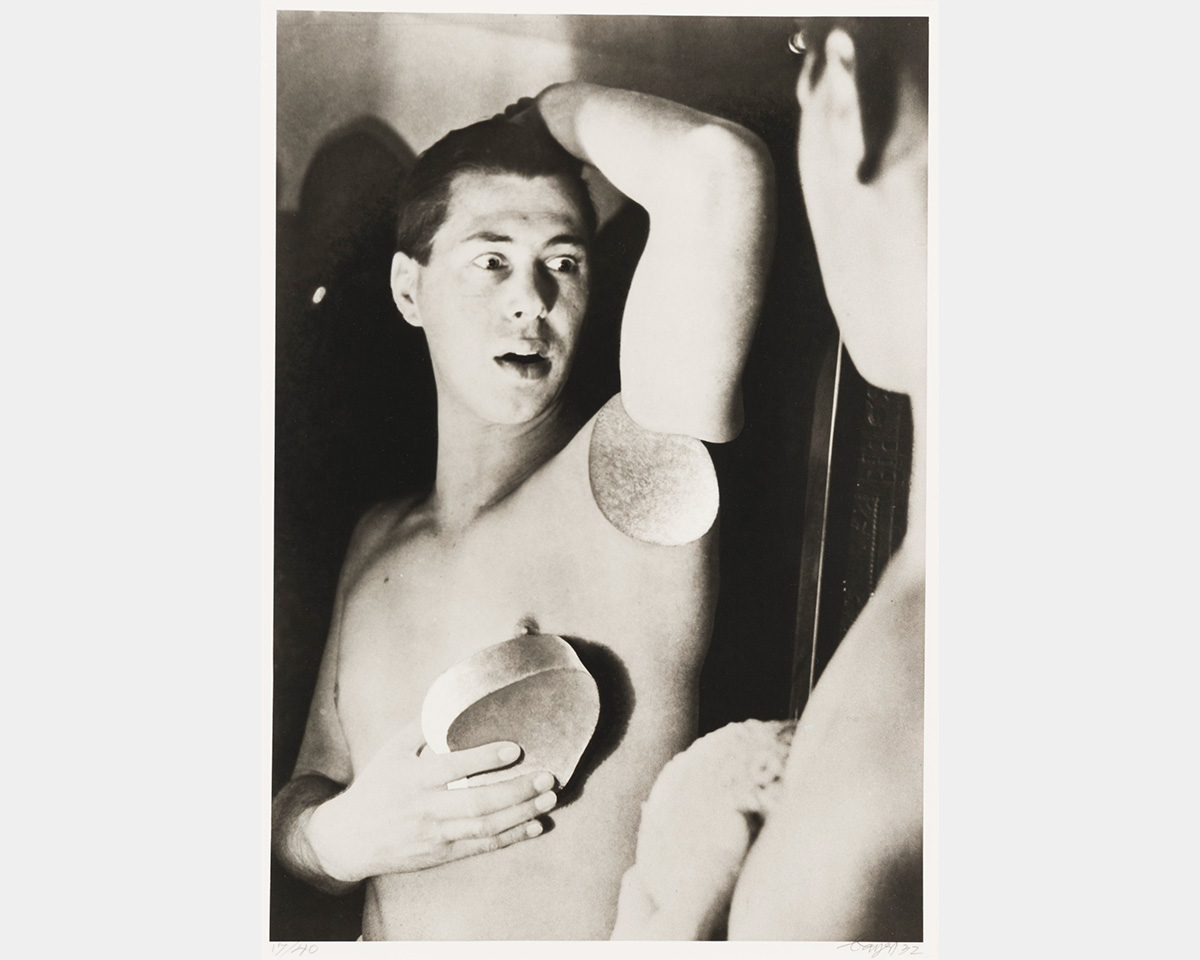

Herbert Bayer (American, 1900–1985), Self Portrait, 1932, gelatin silver print from rephotographed photomontage, The Albert P. Strietmann Collection, 1976.31

Herbert Bayer’s Self-Portrait from 1932 captures a nightmare come to life! The image shows the artist —looking horrified in the mirror— holding a chunk of his own armpit.

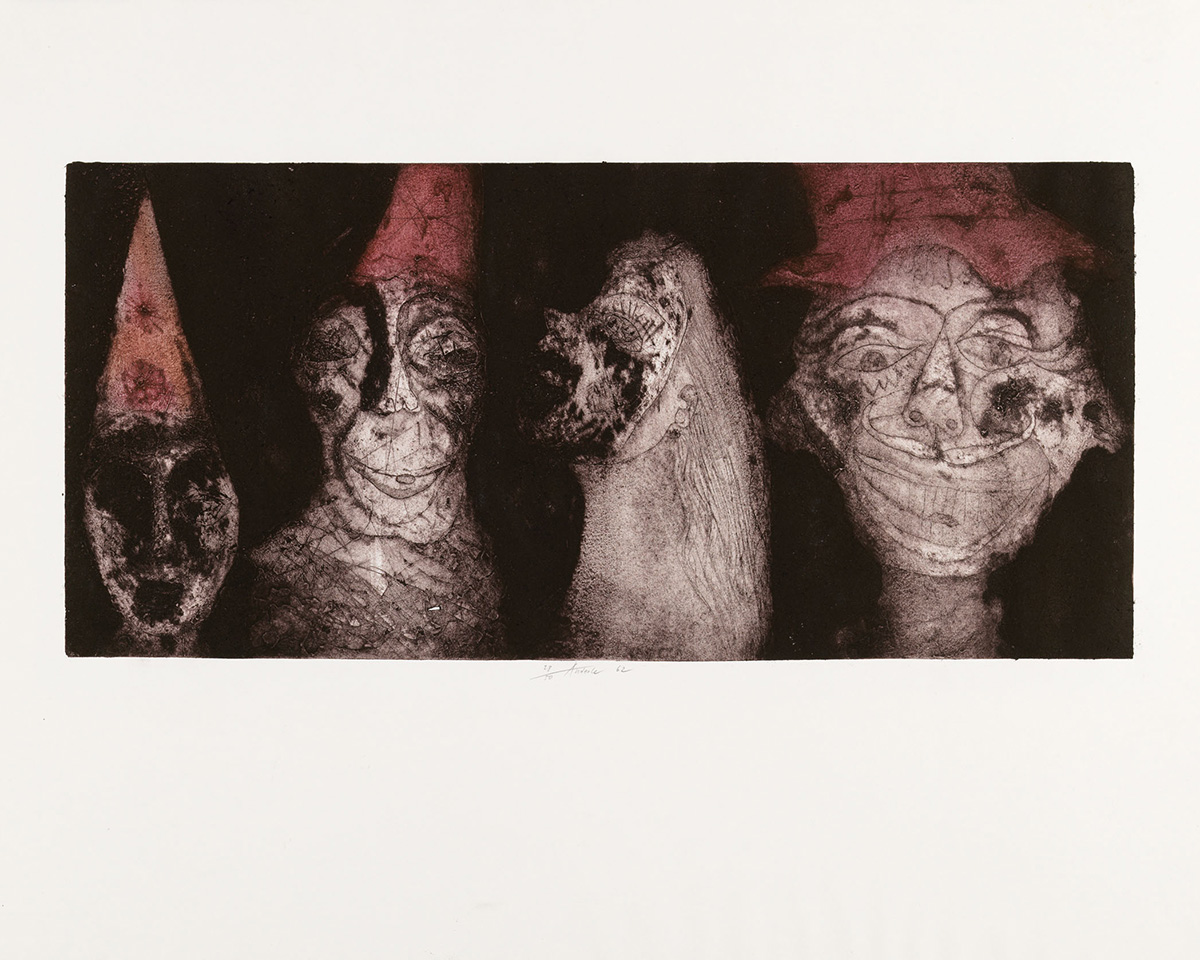

Jiří Anderle (Czech, born 1936), Four Masks (Vier Masken), 1962, color drypoint and collagraph à la poupée, Museum Purchase, 1974.360

Czech painter and printmaker, Jiří Anderle’s work is heavily influenced by the turbulent history of his home country, particularly during his childhood. This print, Four Masks (Vier Masken) from 1962, is from his early career and plays with the extremes of life—young and old, the beautiful and the grotesque—through the grimaces of masks. Though dark and unsettling, Anderle’s prints reflect his observations of human nature and, ultimately, an optimism about humanity’s potential.

Miniature Votive Shield with Head of Alexander the Great as Gorgoneion, 3rd century BCE, Greece, mold-made terracotta, Museum Purchase: Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund, 2007.66

Showing the head of Alexander the Great surrounded by a border of snakes—and with a snake around his neck—this small votive shield is a multi-faceted ward against evil. Its power comes mainly from its reference to the aegis, a shield wielded by Zeus and Athena which bore the severed head of Medusa. The terrifying visage of the gorgon, with her snake hair and grotesque face, was a powerful deterrent for the enemies of the gods. That power is borrowed here and recombined with an image of the deified Alexander, creating an effective talisman against malevolent forces.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: