- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Accra and London, via Detroit

by Nathaniel M. Stein, PhD, Curator of Photography

11/13/2023

Accra , London , James Barnor , Curatorial Blog , photography , Detroit Institute of Arts

In early October, I was delighted to participate in a scholars’ day at the Detroit Institute of Arts (DIA). For those outside the museum biz, a scholars’ day is a convening of curators, academics, and sometimes expert collectors, artists, and gallerists, who gather to share a deep dive on an artist or movement featured in a special exhibition. For the host curators, it’s an opportunity to share deep research underlying an original exhibition project—only a fraction of which surfaces in wall texts and checklists—and to gain new insight by looking and thinking alongside outside specialists who may bring different perspectives. For attendees, a scholars’ day is a welcome and surprisingly rare opportunity to focus on art—usually a less familiar body of work or a new set of questions—away from the incessant chime of one’s email inbox. It is a bit like being back in graduate school for a day, but with a nice lunch and less group insecurity.

Sophie Culière (James Barnor Archive Manager, Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris) speaks in the exhibition James Barnor: Accra/London—A Retrospective. James Barnor Scholars’ Day, Detroit Institute of Arts, October 2, 2023.

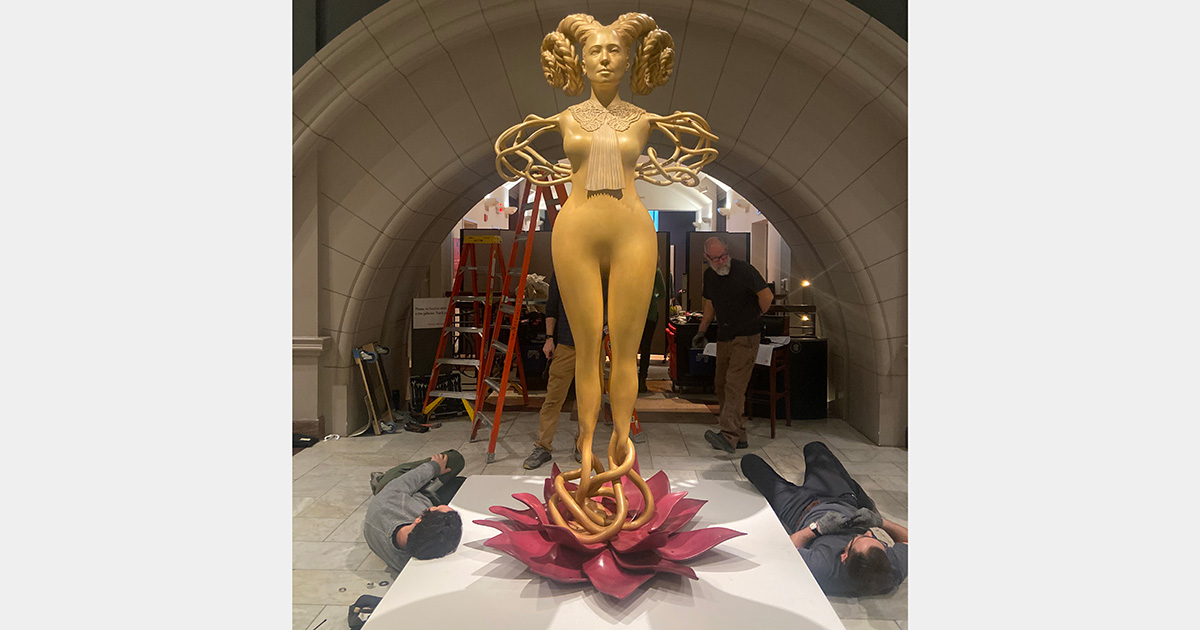

This particular scholars’ day, co-convened by DIA curators Nancy Barr and Nii Quarcoopome, focused on Ghanian photographer James Barnor (b. 1929, active Accra and London). Barnor’s work was the subject of a fantastic retrospective exhibition organized by the Serpentine Galleries, London in 2021, which had its sole North American presentation at the DIA in 2023.

If you know James Barnor’s photography, it may be through his 1960s work for the magazine Drum, a key publication in the UK/Africa diaspora community—or through the influence of his incredibly stylish pictures on other photographers. But the DIA retrospective told a much bigger story, using vintage prints and beautifully produced modern prints to trace Barnor’s six decades working across two continents as a portraitist, photojournalist, Black lifestyle photographer, social documentarian, political voice, and technological innovator. (Barnor is credited with bringing color photography to Ghana in the 1970s.)

Those in attendance were privileged to hear presentations about the complex history of Barnor’s archive, currently stewarded by Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Paris, and about Barnor’s representations of Black femininity. One of the things that was most on my mind, however, was the way in which this scholars’ day in 2023 connected to one I attended nearly a decade ago, about the twentieth-century American photographer Paul Strand. In the early 1960s, Strand was invited to photograph newly independent Ghana by its then president, Kwame Nkrumah. From different points of view and for different audiences, Strand and Barnor each portrayed Ghana as a complex modern place, full of energy, optimism, and promise.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: