- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

An Unexpected Request Leads to a Dramatic Story

by Allie Blankenship, Curatorial Assistant, Photography

12/8/2025

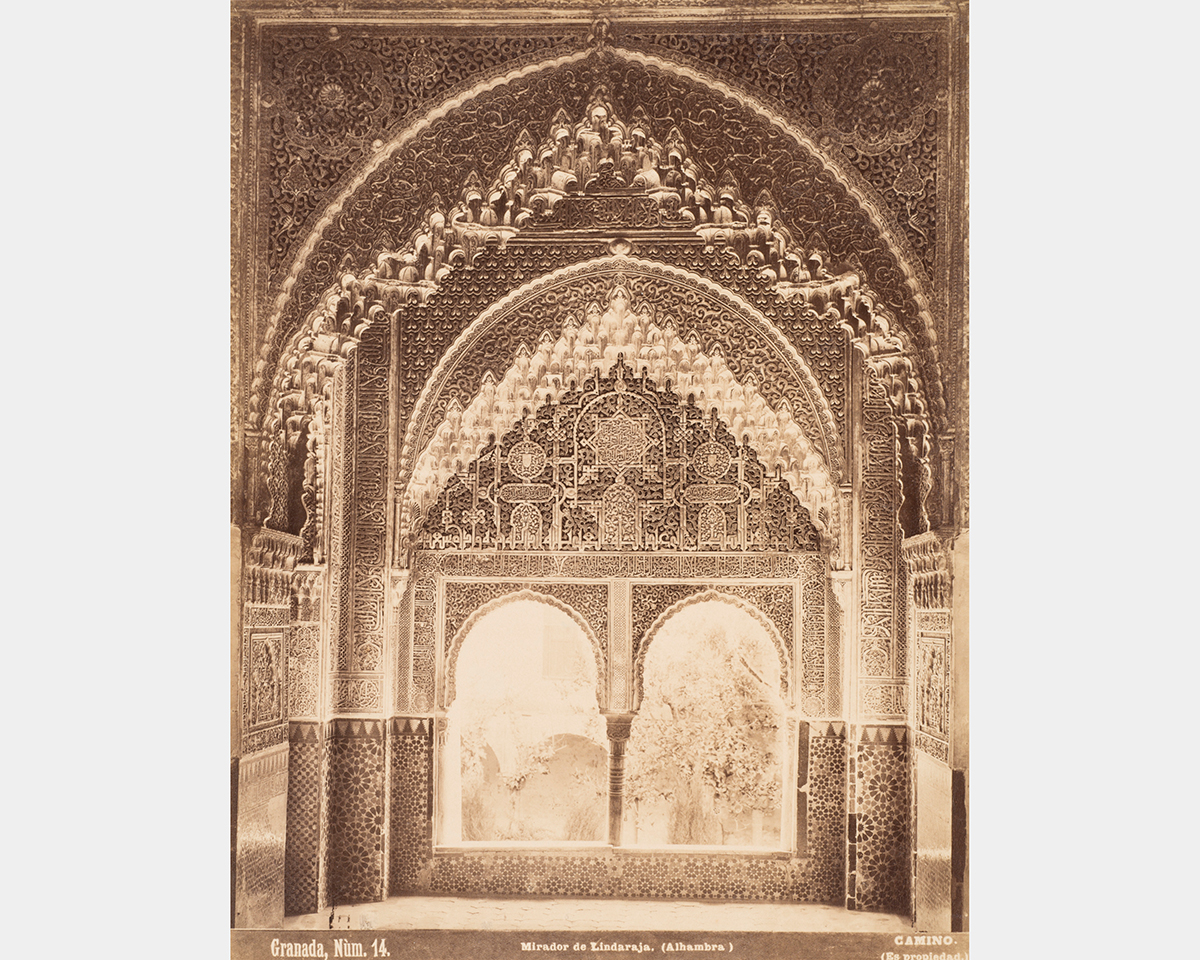

José Camino y Vaca (Spanish, 1846–1892), Mirador de Lindaraja (Alhambra), Granada, 1878–1888, albumen silver print, 1986.603, Gift of George William McClure, Jr.

Read on to learn how an unexpected request from the Cultural Office of the Embassy of Spain led to new information about the dramatic life of the photographer originally known to us only as “Camino.”

As a member of the Curatorial department, we are often approached by members of the public—both in the U.S. and abroad—to share more about the works in the museum’s collection. However, it’s very rare that a request would come from someone so official. The ask was simple: the Cultural Office of the Embassy of Spain was asking for museums across the U.S. to share the works by Spanish artists in their collections to be compiled into a singular website. So when the request from the Spanish Embassy came last year, I excitedly went to our collections database to see if any Spanish photographers were in our collection. I found one, a photographer going by the name ”Camino,” paired with an image of the Alhambra in Granada, Spain.

When I began my research, my main goals were to find any life details and to find sources to give the work a more defined creation date than ”nineteenth century.” My internet searches for Camino almost exclusively pulled up resources for the famous Spanish pilgrimage of the same name. It was only when I ran a reverse image search that I was able to find some clues. An image from the Rijksmuseum in the Netherlands returned an image of an albumen print, also taken in Granada, with a strikingly similar font, but a different name: Señán y González. Not expecting any meaningful results, I decided to search for Señán’s name along with Camino’s. Linking the two allowed me to find the dramatic story that would give me the information I was looking for, along with some salacious details.

José Camino y Vaca (1846–1892) was a prominent Spanish photographer who ran his own studio, Gran Fotografía Universal, which operated in Granada from 1878 to 1888. (Some scholars argue that his studio career began in 1873 and ended in 1886.) For a brief time near the studio’s founding, Camino brought on an apprentice, Rafael Señán González, at the tender age of 14.

Camino was nationally acclaimed, but the later years of his life were marred with controversy: he was arrested and imprisoned as an accomplice to a murder in 1889. Señán—by 1889 a photographer in his own right—returned to the studio to oversee its closure. It is likely that Señán produced and sold his own photographs from his former mentor’s studio during this period.

Once out of prison, Camino began an affair with Señán’s 18-year-old sister, resulting in a child. He also began working in another photographer’s studio. After leaving work one day to congregate at a nearby restaurant, Camino started a verbal and later physical altercation with his former apprentice, Señán. The incident ended with Señán shooting Camino, who died en route to the hospital. Señán was tried twice and acquitted twice, both juries concluding that he shot the elder photographer in self-defense.

While the resulting details were far more dramatic than expected, targeted research opportunities like this allow us to discover the rich histories of the works in our collection and share them with you, the visitor!

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: