Celebrating Black History Month

by Cincinnati Art Museum

1/30/2023

February is Black History Month—a time to recognize the accomplishments and struggles of Black people throughout history. Join the Cincinnati Art Museum during this time of celebration by exploring works by Black artists in the museum’s collection.

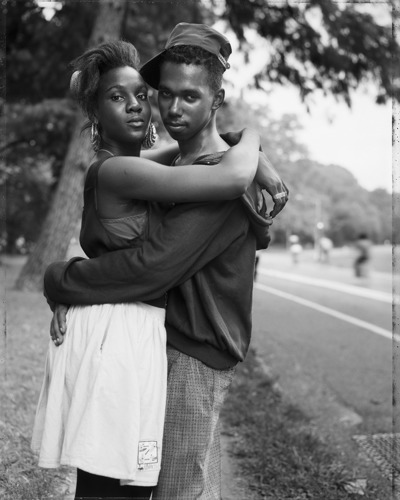

Dawoud Bey (b. 1953)

Dawoud Bey (American, b. 1953), A Couple in Prospect Park, from the series Polaroid Street Portraits, 1990, printed 2022, inkjet print, Museum Purchase: FotoFocus Art Purchase Fund, 2022.201. See this artwork in Gallery 150.

In his decades-long portraiture practice, Dawoud Bey tries to “respond to the challenge of finding meaning in a compelling description of the faces and personas of strangers.” To make the series Polaroid Street Portraits, Bey used a large camera on a tripod, together with film that allowed him to give the people he photographed a copy of the picture on the spot. These choices slowed down Bey’s encounters with people who agreed to be pictured, allowing them time to compose themselves in relation to each other, the photographer, and an imagined future viewer. “I can’t anticipate subtleties like the drape of her hand or the placement of his hand—the little poetic gestures or grace notes,” Bey has said. “I have to let them evolve and recognize them when I see them.”

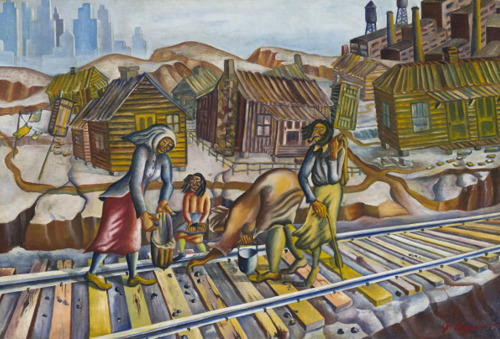

John Biggers (1924–2011)

John Biggers (American, 1924–2011), The Gleaners, 1943, oil on canvas, Museum Purchase: Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. Wichgar and the Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Leyman Endowment, 2022.6. See this recent acquisition in Gallery 211.

A reproduction of Jean-François Millet’s The Gleaners of 1857 in a North Carolina classroom inspired John Biggers, years later, to restage the iconic French painting for contemporary urban America. In Millet’s painting, poor rural women perform the back-breaking labor of collecting grain abandoned in the fields after the harvest. Similarly, Bigger’s The Gleaners depicts a group of Black women on the outskirts of a shimmering city picking up coal dropped by trains on the railroad tracks to sell for a meager existence.

Biggers painted The Gleaners as a student at Hampton Institute in Virginia, a historically Black college. There he engaged in impassioned conversations around social inequities and the power of art to generate public sympathy and change. His mentors were the paint Viktor Lowenfeld, a Jewish refugee, the sculptor and printmaker Elizabeth Catlett who joined the faculty, and Catlett’s then husband Charles White, who painted murals on campus.

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012)

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915–2012), Phillis Wheatley, 1973, bronze, Museum Purchase: Dr. Sandy Courter Memorial Fund, Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund, A. J. Howe Endowment, Henry Meis Endowment, Phyllis H. Thayer Purchase Fund, Israel and Caroline Wilson Fund, On to the Second Century Endowment, 1999.215, © Catlett Mora Family Trust/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. See this artwork in Gallery 211.

In 1973, at a conference on women poets, writer Margaret Walker suggested to Elizabeth Catlett that she make a sculpture of Phillis Wheatly, the first published Black poet. Wheatley was born in Senegal and sold into slavery as a child. The Wheatley family of Boston purchased her and provided her with a classical education. After the publication in 1773 of her Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral, Phillis Wheatley was emancipated. She was the author of about 145 poems and corresponded with George Washington and other leading statesmen.

Catlett used the only known portrait of Wheatley, the engraved frontispiece to her book, as a guide. She simplified the details of Wheatley’s clothing to produce an image of the poet that is both iconic and contemporary. She also abstracted Wheatley’s features to resemble an African mask, which contributes to the stoic appearance. These subtleties are significant both to Catlett’s interests as an artist and to Wheatley’s legacy.

During her graduate studies at the University of Iowa, Catlett was influenced by painter Grant Wood, whom she admired for his belief in the artist’s social responsibility. From Mexican muralists, the African Art collection at the Barnes Foundation, and the European masters, including Van Gogh, Catlett drew on a range of creative traditions. Invigorated by the black power and feminist movements, she has specialized in images of empowered women, often Black or Mexican throughout her career.

Listen to a museum staff member discus Catlett’s work in this CAM Look Episode posted on May 19, 2020.

Robert S. Duncanson (1821–1872)

Robert S. Duncanson (American, 1821–1872), Blue Hole, Flood Waters, Little Miami River, 1851, oil on canvas, Gift of Norbert Heermann and Arthur Helbig, 1926.18. See this artwork in Gallery 107.

On May 30, 1861, the Cincinnati Gazette hailed Robert Duncanson, “the best landscape painter in the West.” The son of free African American parents, Duncanson painted in the Hudson River School tradition, achieving success despite the racial discrimination of the day.

The young Duncanson arrived in Cincinnati, where he would live for most of his life, in about 1840. By that time the city was becoming established as the western outpost for landscape painting. Numerous artists called Cincinnati their home; significant exhibitions included works by the most influential figures, such as Thomas Cole and Asher B. Durand; and growing wealth supported cultural life. Duncanson’s landscapes, such as Blue Hole, were inspired by Cole, but were distinctively meditative. His landscapes and his equally sensitive still lifes earned him generous patronage, especially among Cincinnati’s prominent abolitionist sympathizers.

The beauty of the scenery around the Ohio River attracted Duncanson and other landscape painters such as William Sonntag and Worthington Whittredge. The Blue Hole, a deep mirrorlike pool on the Little Miami River, a tributary of the Ohio, had been a favorite spot for artists since the early 1830s. (It is located now in John Bryan State Park.) Duncanson’s rendering of the site is distinguished by the simple geometry of its composition, its delicate palette of silvery blues and greens, its soft fluent brushwork, and its sweetly poetic mood.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Duncanson’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on June 26, 2020.

Sam Gilliam (1933–2022)

Sam Gilliam (American, 1933–2022), Arch, 1971, acrylic with fabric dyes on canvas, Museum Purchase with aid of funds from the Cincinnati Art Museum Women’s Committee, Pogue’s, and the National Endowment for the Arts, 1975.3. See this artwork in Gallery 231.

By the 1970s, Sam Gilliam had developed painting techniques influenced by Jackson Pollack and Helen Frankenthaler that were related to Abstract Expressionism. Gilliam’s paintings are often referred to as controlled chaos, where the movement of poured paint plays a key role in the composition. He also began to experiment with the concept of what makes a painting. Moving beyond the rectangular canvas stretched over bars, Gilliam began to create works like Arch that draped from walls and ceilings. Their folds push these paintings into three-dimensional space their appearance changes each time they are installed. As Gilliam said, “Arch can be draped in different ways, according to where it is; according to how tall the person who’s draping it is; according to the way that you want it to be seen. But I’m best as doing it.”

Listen to a museum docent discuss Gilliam’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on October 30, 2020.

Terence Hammonds (b. 1976)

Terence Hammonds (American, b. 1976), Breakfront Pottery (Cincinnati, Ohio), Wave Pool (Cincinnati, Ohio; est. 2014), Protest Platter, 2020, glazed stoneware, 14” diameter, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase with funds from the Friends of African American Art, © Terence Hammonds 2020, 2020.37. This artwork is currently not on view.

Terence Hammonds creates work, often print-based, that provokes dialogue about history, race, activism, and change. This platter is part of an editioned set designed by Hammonds and created in collaboration with Breakfront Pottery (Cincinnati) and local refugee and immigrant artists of The Welcome Project of Wave Pool Gallery (Cincinnati). In designing these Protest Platters, Hammonds collected and drew upon approximately 60 images of protest throughout history to create the printed transfers. “I wanted to grab things from various movements, from environmental, civil rights, immigrant rights, women’s rights and gay liberation movements,” he explained. “I chose images of people that were holding signs that were in first person and had the appearance of coming from a deeply personal space.” The form of the large, rimmed platter was designed in collaboration with Breakfront Pottery, while a group of emigre artists from the Welcome Project were employed to apply the transfers.

“I like to think of the platters as maybe having the reverse function of a ‘mammy jar’,” says Hammonds. “Whereas ‘mammy jars’ would reiterate racist stereotypes in subtle innocuous ways, I wanted the platters to remind us of the social struggles and the people who fought for change, and [who] empower us to keep up that fight in our daily lives.”

Listen to a museum docent discuss Hammond’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on October 12, 2020.

Gee Horton (b. 1983)

Gee Horton (American, b. 1983), The Sweetest Thing, from the series Coming of Age, 2021, charcoal and graphite, Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Endowment for contemporary art, 2022.14. This artwork is currently not on view.

Gee Horton’s work navigates and investigates his growth as a Black man in American culture. His hyper-realistic charcoal and graphite drawings contrast the human form with cultural symbols, exploring personal and cultural histories and experiences through unique and arresting portraiture.

The Sweetest Thing, writes Horton, “renders childhood innocence for a little girl who is simply drawn to beauty. The beauty of sunflowers. The way they open to the sun. The way they follow the sun. And, the beauty of her hair. Her hair is an extension of her entire being. It is beautiful. Her beauty touches everything, but she’s unaware of it because of her innocence. Her hair and sunflower feel like magic. They make her feel a sense of wonder, delight, and happiness. This piece is conceptualized to celebrate and affirm the innate innocence and vulnerability of black girls. This drawing consists of 200 ft of box braided hair that is attached (interior and exterior) on the customized framed shadow box. The sunflower is three-dimensional, made of archival floral paper which was hand-crafted by Toronto-based Floral Artist, Jessie Chui.”

Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000)

Jacob Lawrence (American, 1917–2000), Fruits and Vegetables, 1959, tempera on hardboard, Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Leyman Endowment, 2003.260, © 2016 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. See this artwork in Gallery 211.

Although narrative series such as The Migration of the Negro earned Jacob Lawrence early fame and success, scenes depicting daily life in a Black community were a recurring subject throughout his long career. Born in Atlantic City, Lawrence was raised and trained in Harlem, where he began to develop his signature style at an early age. Working in what he referred to as "Dynamic Cubism," Lawrence melded the fracturing of space he found in early twentieth-century Cubism with a vivid, patterned use of color that recalls traditional African textiles. In Fruits and Vegetables, Lawrence used color and pattern to activate his composition; the striped awning at the upper right echoes the dress of the woman at lower left. Repeated colors and shapes of the fruit in the stands punctuate the image and flatten the space. Lawrence’s characteristic enlargement of heads and hands guides the viewer’s eye and emphasizes the movement and rhythm of the scene. Here, Lawrence straddled the line between abstraction and representation; the action takes place in a believable space created by effective layering of elements, yet the painting is simultaneously a virtuoso display of flat color and pattern.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Lawrence’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on May 12, 2020.

Edmonia Lewis (1844–1907)

Edmonia Lewis (American, 1844–1907), Hiawatha’s Marriage, 1871, marble, On loan in loving memory of Drs. George and Sarah Hale, L11.1993. See this artwork in Gallery 217.

The daughter of a Black father and a Chippewa mother, Edmonia Lewis was the first American person of color to earn an international reputation as a sculptor. Lewis was orphaned when young and raised among her mother’s people. A brother saw to her education and ultimately paid for her attendance at Oberlin College in Ohio.

Supported financially by Boston abolitionists, Lewis settled in Italy where a group of American women sculptors challenged the obstacles set by the art establishment. Lewis embraced the neoclassical style, then dominant for sculpture, but combined it with subject matter related to her dual heritage. The theme of this work is the marriage of Hiawatha and Minnehaha from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Song of Hiawatha.” The sculpture’s expression of deep affection and its association of native peoples with the ancient Greeks provide a sympathetic view of Indigenous people at a time when their cultures were threatened with extinction.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Lewis’ work in this CAM Look episode posted on March 25, 2020.

Ann Lowe (1898–1981)

Anne Lowe (American, 1898–1981), Dress and Belt, 1935–38, silk, Anonymous Gift, 1999.811a-b. This artwork is currently not on view.

Born in Clayton, Alabama in 1898, Ann Lowe was a Black fashion designer, but few know her name. In fact, in 1964, the Saturday Evening Post ran an article titled “Ann Lowe: Society’s Best Kept Secret,” and she was just that. Kept a secret because she was Black, her name was passed surreptitiously among the crème-de-la-crème of society, but never acknowledged outwardly. Still today, few know that she designed Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding dress for her marriage to John F. Kennedy in 1953. When Lowe arrived in Newport, Rhode Island to deliver the gown, the staff refused to allow her to enter by the front door, telling her to go to the back. Insistent, Lowe stated she would take the dress home with her, if she was not allowed in the main entrance.

Having learned to sew from her grandmother and mother, Lowe attended a design school in New York where she was segregated from the other students. She won the respect of her instructors, however, because of her exceptional workmanship. Lowe opened her first salon in Tampa, Florida, but by the late 1920s she had moved to New York where she worked on commission. In 1950, she opened Ann Lowe Gowns, making couture dresses.

The museum now holds four dresses by Lowe. Three were given by an anonymous donor including this piece. A Lowe trademark—the flower—is shown here in her choice of fabric, printed with a Japonesque version of the chrysanthemum. Each of the other pieces in the museum’s collection also incorporates the flower into the design.

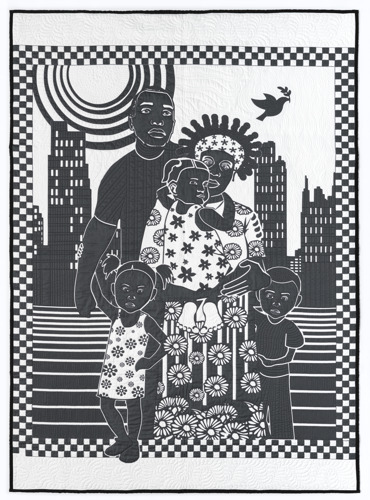

Carolyn Mazloomi (b. 1948)

Carolyn L. Mazloomi (American, b. 1948), Sacred Union, 1999, printed and stenciled cotton, machine quilted, Fashion Arts and Textile Deaccession Fund, 2021.8. This artwork is currently not on view.

Born in Baton Rouge in 1948, Carolyn Mazloomi comes from a family of artists—both visual and performing—although none of her relations made quilts. Trained as an aerospace engineer, Mazloomi moved to Ohio, taking a position at General Electric. It was, however, a fortuitous move as Ohio and its surrounding states are historically a hotbed for quilt making, and she met many quilters here.

Mazloomi is drawn to create quilts about vulnerable people who she feels deserve to be seen, heard, and understood. Her intention is to invite the viewer into contemplation and raise awareness concerning issues with which they may be unfamiliar. Mazloomi is particularly interested in telling stories about women through her quilts. As mothers, they influence every human being on the planet.

This particular piece combines Mazloomi’s love of storytelling with her interest in depicting women. The father in this family unit is present, but he is depicted in black and seems to fade into the background. Even the other male—the young boy—is portrayed in black. Our eyes focus on the mother with her expressive hair style, her bright floral clothing, and the two female children clinging to her. The woman is the glue holding this family together and the primary focus of our attention.

Mazloomi has gained much recognition for her quilts. Having shown her work in over 74 exhibitions at prestigious museums, her quilts can be found in both private hands around the world and distinguished museum collections, including the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Perhaps most significant is her founding of the Women of Color Quilters Network (WCQN). Established in 1985, Mazloomi has been at the forefront of educating the public about the diversity of interpretation, styles, and techniques of Black quilters and a younger generation about their own history.

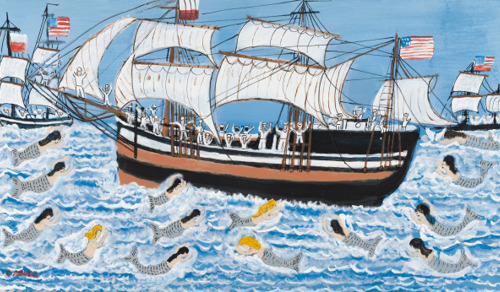

Charles A. Owens (1922–1981)

Charles A. Owens (American, 1922–1981), The Bark Patriot, circa 1980–97, acrylic on board, Gift of Dr. Dale G. and Ann Knight Gutman in honor of The Ohio Folk Art Association, 2018.277. See this artwork in Gallery 219.

Charles A. Owens grew up in Maysville, Kentucky, the child of an opera singer and saxophone player. In 1949 he moved to Columbus, Ohio, where he was a contemporary with fellow Black folk artist Elijah Pierce. To support his family, Owens worked several jobs, among them a chef, ice cream maker, construction worker, bootlegger, and mechanic. He enjoyed painting and drawing in his spare time, though he produced most of his work after he retired.

Owens found inspiration for his paintings in his memories, the world around him, and in his books. The Bark Patriot is a combination of history and fantasy. According to an inscription on the back, the ship was a trading vessel built in 1809 and used by Salem, Massachusetts, merchants. Owens took great care to delineate the complicated rigging and billowing sails of the ship. Yet, his whimsical composition surrounded the “Patriot” with mermaids, much to the excitement of the sailors.

Gordon Parks (1912–2006)

Gordon Parks (American, 1912–2006), Untitled, 1956, vintage gelatin silver print, Museum Purchase: Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund, 1999.15, © Gordon Parks Foundation

Gordon Parks, a world-renowned photojournalist and filmmaker, is known for his work documenting American life and culture. His iconic photography focuses on issues of race, poverty, civil rights and urban life. Parks stated, “I suffered first as a child from discrimination, poverty ... So I think it was a natural follow from that that I should use my camera to speak for people who are unable to speak for themselves.”

Parks was the first Black staff photographer for Life, and with his film adaptation of his semi-autobiographical novel, The Learning Tree, became the first to direct a major Hollywood studio feature film.

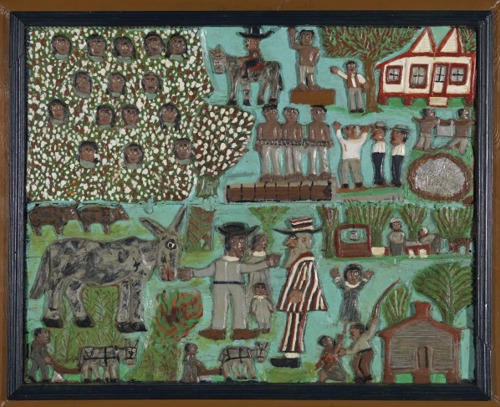

Elijah Pierce (1892–1984)

Elijah Pierce (American, 1892–1984), Slavery Time, 1965–1970, carved wood relief painted in acrylic with glitter and pearls, Museum Purchase: Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund. 2006.117. See this artwork in Gallery 219.

Among the foremost self-taught relief sculptors of the twentieth century, Elijah Pierce was born on a farm in Baldwyn, Mississippi, where as a young child, he whittled small animal figures. Eventually settling in Columbus, Ohio, Pierce opened a barbershop that also functioned as an art gallery. There he displayed his most personally significant works.

This bas-relief recounts many of the things Pierce’s father, who was enslaved for much of his life, likely would have seen and experienced. Clockwise from the upper left the scenes depict: an overseer watching enslaved people work in a cotton field; an enslaved person sold on an auction block; enslaved people carrying food past a master’s house; three chained people forced to eat from a trough; a group of enslaved people washing clothes by a well; an enslaved person being whipped; an emancipated person confronting Uncle Sam, referencing the promise of forty acres and a mule to all emancipated peoples; and emancipated people tilling their own land.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Pierce’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on February 19, 2021.

Horace Pippin (1888–1946)

Horace Pippin (American, 1888–1946), Christmas Morning, Breakfast, 1945, oil on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1959.47. This artwork is currently in Gallery 211.

Horace Pippin shows the grandeur in the ordinary lives of common folk. In this autobiographical work, a mother serves pancakes while her son sits patiently with his hands folded in prayer, waiting to eat breakfast. The home’s poverty is evident in the exposed wallboards where large chunks of plaster have fallen away, and the mother’s life of unremitting labor is evident in her bowed back. Yet the painting glows with familial warmth between the two figures, and the neatness of the room suggests domestic order.

Pippin was self-taught and regarded himself as a realist. "I don’t go around making up a whole lot of stuff,” he sad. “I paint it exactly the way it is and exactly the way I see it." Pippin’s method was not academic. "Pictures just come to my mind," he explained, "and I tell my heart to go ahead." Pippin developed a simplified, abstract manner based on a stylization of natural forms arranged in flat patterns. He used delicate line and subtle coloring for his poignant narratives.

Pippin took up painting after returning home from World War I where he sustained a permanent injury after being shot in the right shoulder and could no longer support himself as a laborer. During his lifetime, he achieved art world recognition for paintings such as this one.

Listen to a museum docent discuss Pippin’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on December 23, 2020.

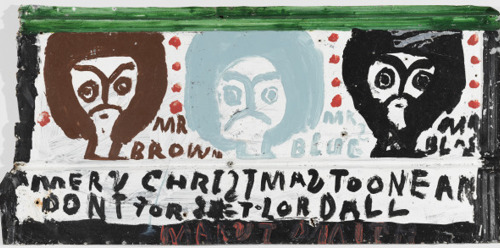

Mary T. Smith (1904–1995)

Mary T. Smith (American, 1904–1995), Mr. Brown, Mr. Blue, Mr. Black (Merry Christmas to One and All), circa 1985, oil on corrugated tin, Gift of Robert Alan Lewis, L1.2007:34. See this artwork in Gallery 219.

Mary Tillman Smith said she began “making pictures” when she was in her seventies to “pretty up my yard.” Fences on her one-acre property in Hazelhurst, Mississippi, became a gallery for her bold works, which Smith made using house paint with a broad brush on plywood panels or roofing tin cut with an axe. She expressed her deep religious faith with idiosyncratic sayings integral to her compositions.

Smith was one of thirteen children from a family of sharecroppers. As a child, she began to draw as a release from the frustration of a hearing impairment that left her speech difficult to understand. Her burst of creativity came after retirement from decades of labor as a tenant farmer, a cook, and a gardener.

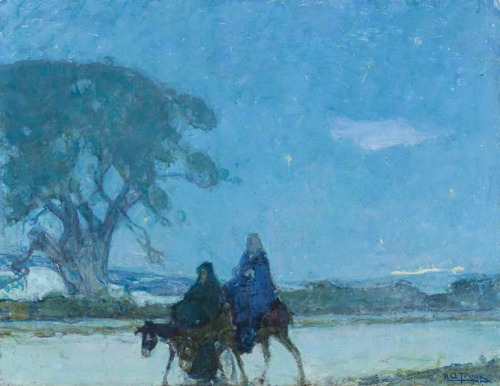

Henry Ossawa Tanner (1859–1937)

Henry Ossawa Tanner (American, 1859–1937), Flight into Egypt, circa 1907–12, oil on canvas in hand-carved and gilded frame, Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment, 2002.47. See this artwork in Gallery 216.

Ghostly figures move stealthily across the foreground in this simplified composition, with its low horizon line and unearthly blue sky. For Henry Ossawa Tanner, whose father was a bishop in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, biblical themes such as the Flight into Egypt provided a means to express his family traditions and spirituality. Tanner may have associated this story from the Book of Matthew (in which the Holy Family flees into the desert to escape persecution by King Herod) with his own struggles against racism. Tanner settled in France, finding his work judged on its merits there without concern for his race. He owed his Paris education to the support of Cincinnatians Bishop Joseph Crane Hartzell and Clara Hartzell, who arranged for his first solo exhibition, held in Cincinnati in 1890. When the paintings failed to sell, the couple bought them to fund the artist’s studies abroad.

Listen to a museum docent member discuss Tanner’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on April 12, 2022.

Mose Tolliver (circa 1915–2006)

Mose Tolliver (American, circa 1915–2006), Four Figures, 1980s, Latex paint on plywood, Gift of Robert Alan Lewis, L1.2007:51. See this artwork in Gallery 219.

The figures in Mose Tolliver’s painting might be dancing; the V-shapes of the women’s skirts were the artist’s way of denoting movement. Tolliver always painted directly on his boards, without any preliminary sketches, carefully turning the board as he worked. He chose his palette carefully, seldom using more than three colors in an entire piece.

In the late 1960s, while working in the shipping department of a furniture store, Tolliver was severely injured when a crate of marble fell and crushed his legs. Since he could not walk, Tolliver sat at the edge of his bed and propped boards on his lap or on a chair to paint, using—to his wife’s dismay—the bedspread as a paint rag.

Antoine Washington (b. 1980)

Antoine Washington (American, b. 1980), Black Family: The Love, 2021, acrylic on canvas, Museum Purchase: Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Endowment for Contemporary Art, 2021.96. This artwork is currently not on view.

Living and working in Cleveland, Ohio, Antwoine Washington rewrites accepted narratives that touch his lived experience. Showing his family in embrace and empathy, these works are part of a new series of paintings titled The Myth of the Missing Black Father. By contrasting his own life experience raising a strong and thriving family, he takes exception to the negative pervasive stereotype of absent Black fathers. In its vibrant colors and simplified figures, the work pays homage to artists of the Harlem Renaissance and is a celebration of family and joy.

Raised in Pontiac, Michigan, Washington recalls that working as a visual artist did not appear to be a viable career choice. J.J. Evans, depicted on the television series Good Times (1974–1979), was one of the few positive representations of Black artists in his life. Revealing that presence and inclusion often differs from social histories, Washington encourages young artists to write their own stories, thoughts, and experiences through visual art. Prior to acquisition by the Cincinnati Art Museum, this painting was exhibited at the Transformer Station’s New Histories, New Futures exhibition in Cleveland.

Carrie Mae Weems (b. 1977)

Carrie Mae Weems (American, b. 1953), Untitled (Woman with friends), from the Kitchen Table Series, 1990, gelatin silver prints, Museum Purchase: Gift of RSM Co., by exchange, 1995.2a–c. This artwork is currently not on view.

In the 1970s and 1980s, artists and theorists challenged ingrained beliefs about photography. Some pointed out that photographs are not simply facts, but units of visual language dependent on context and laden with meaning much like the written word. Carrie Mae Weems has consistently found moving ways to highlight photography’s layered relationship with text, fact and power, with an eye towards voicing stories that have been left out of the dominant social narrative.

These three pictures come from the Kitchen Table Series, a body of work composed of 20 carefully posed photographs and 14 text panels, together tell the story of a relationship and its aftermath from the perspective of a Black woman. Weems plays her own protagonist in the photographs, tracing a range of experience—from desire to anger to a fully self-possessed sense of womanhood—through a story of which she is the author. This series also poignantly explores the ways in which women support, communicate with, and hold space for each other.

Listen to a former museum staff member discuss Weems’ work in this CAM Look episode posted on May 22, 2020.

Hale Woodruff (1900–1980)

Hale Woodruff (American, 1900–1980), Landscape, circa 1960, oil on canvas, Gift of Laura H. Chapman, 2012.97. See this artwork on view in Gallery 230.

Hale Woodruff is known for establishing the fine arts program at Atlanta University and for his contributions to founding the Black artist group Spiral in the early 1960s. While he is renowned for his early figurative work, less well studied are the abstract paintings he created, while teaching at New York University from 1945–67. Like many artists of his time, Woodruff’s racial identity created barriers when producing non-representational art, as many expected Black artists to portray Black subjects.

Woodruff believed careful compositional planning, rather than a focus on painting processes, was essential to producing successful art. In Landscape, the surface of the painting vibrates with the implied movement of the natural world, captured by Woodruff through juxtapositions of broad areas of saturated color and energetic brushstrokes.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Woodruff’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on February 7, 2022.

Explore works by Black artists in the museum’s open-access Photobook Collection

Browse these physically compact, conceptually expansive works of art at your leisure in the Mary R. Schiff Library. Black artists represented in the museum’s FotoFocus Photobook Collection include Andre Bradley, John Edmonds, Nona Faustine, Rahim Fortune, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Lyle Ashton Harris, Deana Lawson, Cecil McDonald Jr., Zanele Muholi, Donovan Smallwood and many others. Browse the collection.