Celebrating Jewish American Heritage Month

by Cincinnati Art Museum

5/20/2022

During the month of May the Cincinnati Art Museum joins institutions across the country in paying tribute to the generations of Jewish Americans who helped form the fabric of American history, culture, and society.

In addition to learning more about Jewish American artists in the museum’s permanent collection, we invite you to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the city of Cincinnati’s Jewish community with an exciting roster of events taking place throughout the region, including the upcoming special exhibition Henry Mosler Behind the Scenes: In Celebration of the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial (opening June 10). Learn more by visiting Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial.

Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011)

Abstract Expressionism became legendary for paintings of monumental scale, bold gestures, and decisive action. Mythic, heroic masculinity, akin to James Dean in the movies, surrounded the movement’s male artists, who, via media hype, attained iconic stature. This veneration of machismo, epitomized by the image of a muscular Jackson Pollock making his celebrated drip paintings, left little room for the women of the movement, many of whom labored for decades in obscurity.

Helen Frankenthaler achieved some recognition due in part to her marriage to one of the movement’s founding artists Robert Motherwell. Experimenting with Pollock’s idea of pouring paint onto a canvas on the floor, Frankenthaler invented a technique that became highly influential; she stained the raw canvas with washes of brilliant color, achieving a delicate equilibrium between accident and control. Typically, as in Rock Pond, her large, organic forms evoke the experience of nature and landscape. The museum acknowledged Frankenthaler’s achievement by acquiring Rock Pond just a few years after its completion.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Frankenthaler’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on January 26, 2021.

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928–2011), Rock Pond, 1962-63, acrylic on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1969.11, © 2016 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. View this artwork in Gallery 231.

Chaim Gross (1904–1991)

Chaim Gross was born in the village of Wolowa (now known as Mizhhiria, Ukraine) in the Carpathian Mountains in 1902. His family moved around extensively in Eastern Europe before immigrating to the United States in 1921.

Gross grew up in poverty, the youngest of ten children. His family were devout Hassidic Jews, whose faith expresses itself through rejoicing in life and facing its challenges with a festive, optimistic spirit. Central to this way of life was the weekly Sabbath and the necklace of holidays that sparked the drab year with color and light.

Before a young Gross grasped abstract concepts like freedom, morality, repentance or history, these holiday celebrations captured him imagination, bound him in spirit to his family and ancestors, and filled him with values and ideals. Displaced during World War I, Gross immigrated to the United States in 1921, where he studied at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design in New York.

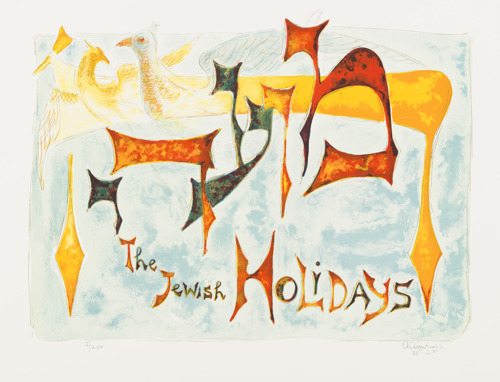

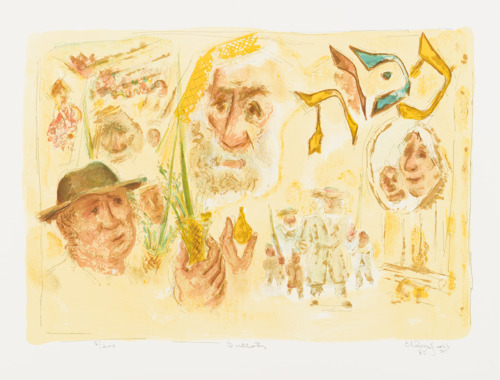

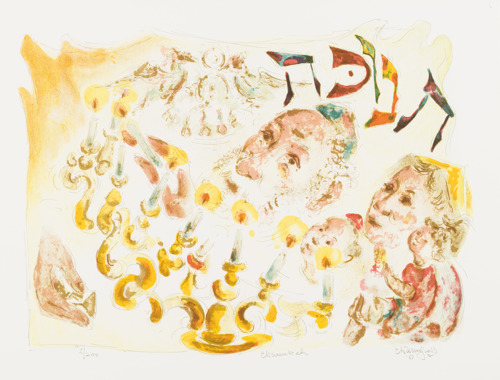

In these lithographs, Gross recaptures the color of his childhood. His skill makes the Jewish holidays come alive for those who have shared the experience. For those to whom this vanished world is mere history, Gross offers emotional insight and aesthetic pleasure. These festivals still live today, but the form and feeling of their observance for four centuries in the Jewish world of Eastern Europe is gone. Through these lithographs, the world breathes again.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss one of Gross’s works in this CAM Look episode posted on March 29, 2021

Chaim Gross (American, 1902–1991), The Jewish Holidays, 1968, color lithograph, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. Sidney A. Peerless, 1973.443.1-11, © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Philip Guston (1913–1980)

Philip Guston (born Phillip Goldstein) was born in Montreal in 1913 after his parents escaped persecution in Odessa, Ukraine and immigrated to Canada. His family later moved to Los Angeles in 1919.

Guston’s work changed dramatically in the late 1960s. He distanced himself from the modernist concept that painting could only be pure if free from imagery, saying, “We are image makers and are image ridden.” Working from dark childhood memories of his father’s suicide, of his own fear of the Ku Klux Klan, and of secretly drawing in a closet lit by a single bulb, Guston moved away from abstraction toward an existential, post-modern style.

Guston’s shift in approach included the development of a personal iconography. Recurring images in his paintings include Klansmen, light bulbs, shoes, cigarettes, and clocks. Guston’s cartoon-like draftsmanship became a key element of his mature style, along with a palette dominated by black, white, and red, as seen in To R.F.

Guston dedicated this painting to his friend, the Cincinnati writer Ross Feld who wrote Guston in Time: Remembering Philip Guston, published posthumously in May 2001.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Guston’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on February 23, 2021.

Philip Guston (American, 1913–1980), To R.F., 1978, oil on canvas, Gift of Musa and Tom Mayer, 2005.636, © The Estate of Philip Guston. View this artwork online.

Henry Mosler (1841–1920)

Mosler was born in Tropplowitz, Silesia, Prussia (present-day Opawica, Poland) in 1841 and moved with his family to New York in 1849. In 1851, the family relocated to Cincinnati, Ohio.

Mosler achieved an international reputation in the late nineteenth century for narrative paintings rich in detail. The artist won success at the Salon exhibitions in Paris for paintings depicting the rituals of daily life in Brittany. Drawn from the extensive collection of the artist’s work at the Cincinnati Art Museum, with a few select loans, the upcoming special exhibition Henry Mosler Behind the Scenes: In Celebration of the Jewish Cincinnati Bicentennial (June 10–September 4, 2022) relates Mosler’s journey and takes a close look at how he developed his paintings through studies across media.

Henry Mosler (American, 1841–1920), Plum Street Temple, 1866, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Skirball Museum; Gift of Audrey Skirball Kenis, granddaughter of the artist, 41.259. View this artwork in Gallery 125 beginning June 10.

Louise Nevelson (1899–1988)

Louise Nevelson was born in the Poltava Governorate of the Russian Empire (present-day Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine) in 1899. She immigrated with her family to the United States in the early twentieth century.

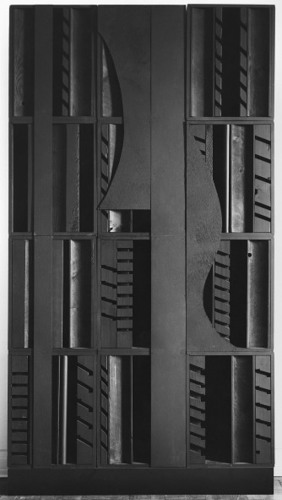

Assembled rather than modeled or carved, and framed in boxes that seem to dissolve form into a pattern of highlights and deep shadows, Louise Nevelson’s remarkable sculptures helped redefine the nature of this medium in the second half of the twentieth century. Taking as her point of departure the notion that found objects can take on new and often unexpected meanings when placed in a different context, Nevelson freely mixed old scraps of wood and architectural fragments such as moldings and carved balusters with a variety of abstract forms that she produced herself.

For Nevelson, the selection and arrangement of objects were clearly as important as the forms of the objects themselves. Her genius lay in her ability to bring abstract forms together in tableaux that strike a universal chord within us without yielding any specific meanings. “Only a few basic forms unify the art of all periods,” she said. “The rest are variations. I build the appearance of a universe from parts of such forms.”

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Nevelson’s work in this CAM Look episode published on January 22, 2021.

Louise Nevelson (American, 1899–1988), Nightscape III, 1974, painted wood, Museum Purchase with the aid of funds from the Cincinnati Art Museum Women’s Committee, Pogue’s and the National Endowment for the Arts, 1975.264, © 2016 Estate of Louise Nevelson / Artists Rights Society (ARS). View this artwork in Gallery 230.

Mark Rothko (1903–1970)

Mark Rothko (born Markus Yakovlevich Rothkowitz) was born in Daugavpils, Latvia (then in the Russian Empire). Rothko, his mother, and sister immigrated to the United States in 1913, shortly after his father and brothers arrived.

In the works of Rothko, the vibrations of one color against another make the hazy-edged shapes seem to hover and pulsate above the surface. These mysterious, contemplative effects stand in contrast to the raw energy of works by his contemporaries, including Hans Hoffman, Franz Kline, and Willem de Kooning, his compatriots? colleagues?.

Rothko explained his motives as follows:

I’m not an abstract artist…I’m not interested in the relationship of color or form or anything else. I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on. And the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate…. The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience as I had when I painted them.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Rothko’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on April 8, 2020.

Mark Rothko (American, 1903–1970), Brown, Orange, Blue on Maroon, 1963, oil on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1982.135 © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. View this artwork in Gallery 230.