- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Reframing the World’s Fairs

by Mackenzie Strong, Curatorial Assistant for Decorative Arts & Design

1/16/2024

World's Fair , World's Columbian Exposition , Chicago , 1893 , propaganda , nationalism , Ida B. Wells , Frederick Douglass , Ferdinand Lee Barnett , Curatorial Blog

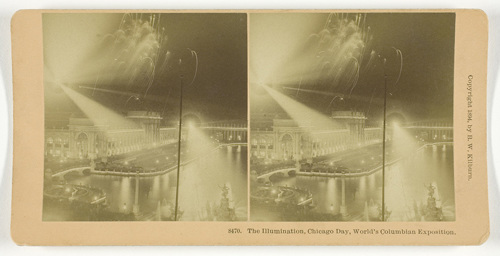

While exploring the museum’s collections, you have likely encountered object titles or labels that feature the phrase “the world’s fairs.” Beginning in the 1850s, these international exhibitions celebrated recent inventions and developments in art, science, technology, and industry. Exhibits at the early expositions featured anything from machinery, pottery, and art-carved furniture to monumental architecture and landmarks commissioned for the events, such as the Eiffel Tower (Paris, 1889) and the Ferris Wheel (Chicago, 1893). Referencing an artwork’s exhibition at a world’s fair, therefore, is often done to emphasize the work’s technical or creative merit.

However, this surface-level explanation of the world’s fairs tells us only a part of their story. If we look at just one example—the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition held in Chicago—we can see how these celebrations of artistic and scientific achievements also communicated complex messages about identity and race.

Like many previous world’s fairs, the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition acted as powerful propaganda for an intentionally narrow vision of national identity. Rooted in harmful racist ideas and white supremacist beliefs, different exhibits at the event revealed assumptions about the cultural, economic, and political superiority of America and Europe. Specifically, the fair’s problematic Eurocentric hierarchies of nations and ideas about “human progress” perpetuated the scientific racism and racialized thinking that already existed within nineteenth-century America.

Contextualizing the racism at the core of one world’s fair structure is essential. Equally—and to further reframe our understanding of these international events—it is important to understand how Black activists also used Chicago’s 1893 Exposition to expose and resist the systemic racism that Americans of color experienced at these events and in daily life. From the very beginning of the fair’s nation-wide preparations, American activists like Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, and Ferdinand Lee Barnett advocated for the better representation of people of color. When event officials and government authorities denied their repeated requests for representation, Wells, Douglass, and Barnett published a pamphlet that highlighted this discrimination. In doing so, these leaders simultaneously emphasized Black Americans’ recent cultural, economic, and scientific achievements.

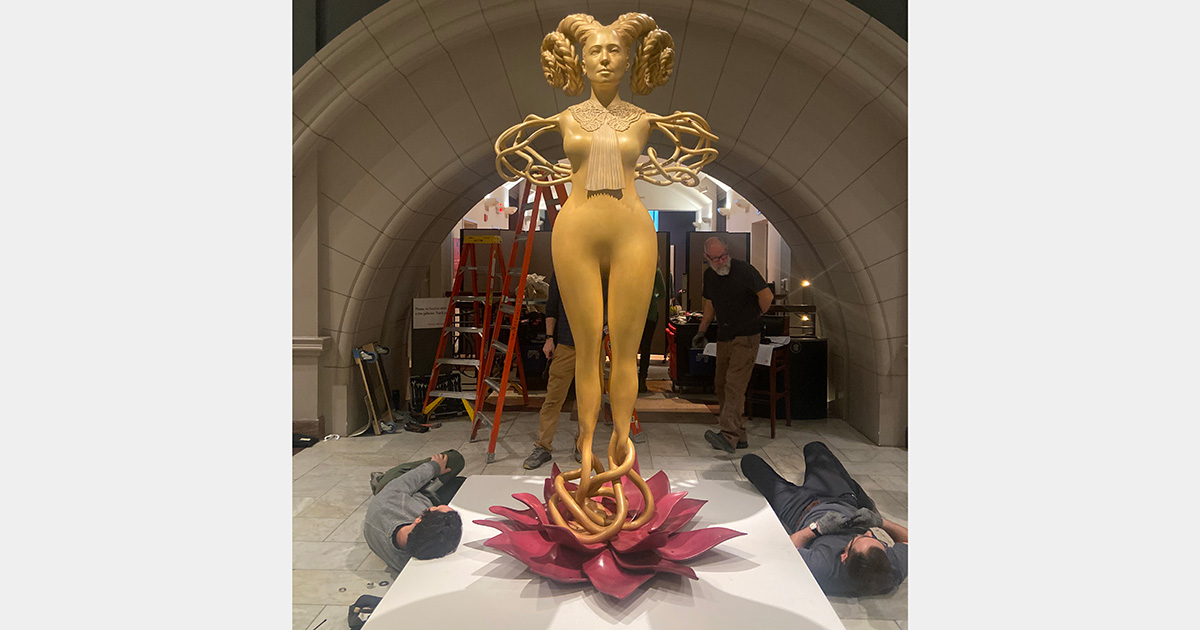

Black activism at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition extended beyond written petitions, as many Americans of color voiced their protests by boycotting the fair. Likewise, direct engagement with and contributions to the exposition’s programming and exhibits possibly provided another outlet for Black Americans’ resistance to systemic inequality. For example, Cincinnati artist and wood carver Adina E. White exhibited a carved tabletop at the 1893 Exposition, which later received national media recognition—despite the fair’s display only crediting the company that employed White. A recent exhibition at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum explored another example of this advocacy through the works that W. E. B. Du Bois created for the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris.

Ultimately, reframing the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition as an event that simultaneously functioned as a celebration of achievement, as propaganda for existing racist ideologies, and as a platform for the social justice activism undertaken by and for Americans of color allows us to understand its material legacy in new ways. You can investigate this layered legacy the next time you visit the Cincinnati Wing and other galleries here at the museum.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: