Seven Ghostly Stops at the Cincinnati Art Museum

by Cincinnati Art Museum

10/18/2022

Our visitors aren’t the only ones roaming the galleries. Is the Cincinnati Art Museum haunted? Find out yourself! We’ve narrowed down the spookiest spots in the museum, equipped with ghostly tales of the unexplained.

Take a self-guided tour … if you dare …

Gallery 107—Calling Out for Company

Samuel Best (American, b. British, 1776–1859), Tall-Case Clock, 1810–1815, mahogany, cherry, inlays of burled maple and flame grained mahogany, poplar, white pine, glass, brass, paint and gilt, Museum Purchase, 1966.1175. On view in Gallery 107.

It seems that certain objects come to life when museum visitors and staff are not looking. Perhaps these objects have brought with them the spirits of their previous owners … or creators. Read on to learn about one such “haunted” object.

Samuel Best, who lived and worked in Cincinnati in the first decades of the 1800s, was a silversmith who crafted everything from engraving plates and silverware to locks and timepieces—including this tall-case clock.

One evening, a curator and an art handler were working late in the museum’s galleries, when suddenly, they hear a loud “BONG, BONG,” coming from the direction of Best’s tall-case clock located in an adjacent gallery. The curator and art handler looked at each other, both realizing that the clock weights had been removed before its installation in the public galleries.

According to the curator, the art handler walked slowly around the corner, and in a moment, he quickly re-emerged.

“It’s time to go home now,” he said, simply—and never spoke of the incident again.

Gallery 110—Parted Too Soon

Clement J. Barnhorn (American, 1857–1953), Frank Duveneck (American, 1848–1919), Memorial to Elizabeth Boott Duveneck, 1891, plaster, Gift of Frank Duveneck, 1895.146. On view in Gallery 110.

After a six-year engagement, artist Elizabeth Boott married artist Frank Duveneck in 1886. Their love was a meeting of minds—and their marriage, a joining of vastly different worlds.

Elizabeth came from a wealthy Boston family, while Frank was Kentucky-born of German immigrants whose family ran a beer garden. They met at one of Frank’s exhibitions in Boston. Later, Elizabeth caught up with Frank in Europe when he was teaching in Munich, Germany. Their extended courtship was a result of her own artistic ambitions, as well as the barriers of class difference.

The couple married just before Elizabeth’s 40th birthday. She had a child, and the family moved to Paris. One evening, Elizabeth and Frank attended an art exhibition. Tragically, Lizzie, as Frank playfully called her, caught a chill on the way home from the opening. In four days, just two years after their marriage, Lizzie died of pneumonia.

Frank created this tomb cover, his only attempt at sculpture, in Elizabeth’s honor; her body graced with palm leaves suggests triumph over death.

On a sluggish Thursday evening, a Visitor Services attendant walked by the tomb cover and, hearing a cough, turned around expecting to see the security guard–but instead faced a deserted gallery.

The only sound she heard was a small voice whispering, “Frank … Frank …”

Gallery 111—Waiting to Cut In

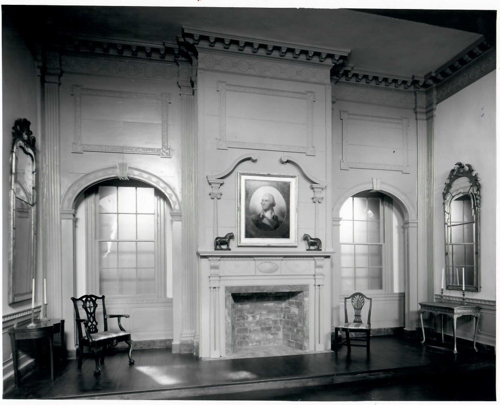

George Andrews (American), James Oldham (American), Ballroom Fireplace Wall from Soldier’s Joy (exterior and interior), 1806, Gift of Mrs. George F. Baker, 1947.626. Not currently on display.

As the tale goes, gallery attendants have seen a man dressed in an American Civil War uniform, strolling through the Cincinnati Wing on the first floor, stopping at times to languidly lean on an invisible wall.

Many years ago, Gallery 111 was home to The Soldier’s Joy Ballroom. Constructed in 1806, the ballroom originally belonged in a manor house in Nelson County, Virginia, the home of Revolutionary War veteran Jordan Cabell. This federal style ballroom remained intact up to and through the Civil War, and the manor house, named Soldier’s Joy, was known to be a popular place for parties and dances at the beginning of the conflict.

Perhaps killed on the battlefield, the museum’s Civil War specter has returned to the spot he remembered best at the time of his death, still watching couples waltzing, and ever vigilant for a chance to cut in.

Gallery 115—A Ghostly Remodel

Nicolas Ducret (French), Jean Hersant (French), Luc Stouf (French), Hillon (French), Salon de L’Hôtel de Saint-Simon Sandricourt, 1760, oak, Gift of Mrs. Herbert N. Straus, 1958.256a-h. Not currently on display.

Before Gallery 115 displayed Rookwood Pottery, it housed a salon from an eighteenth-century French mansion once located on the Rue de Bac in Paris. Collectors Mr. and Mrs. Herbert Straus (heirs to the Macy & Co. fortune) purchased the salon’s paneling from a Paris antique dealer in 1931 and eventually gifted the panels to the museum.

Although the salon hosted many visitors during its long lifetime in Paris, apparently one visitor refused to leave …

For a time, this area of the museum held secretarial offices. One evening, while staff worked late, they heard a fellow staff member moving her furniture around in the adjoining office. Although this seemed a strange thing to do, they all simply laughed and went home.

The next morning, when the staff questioned their office mate about her late hours at the museum, she replied that she had gone home at 5 p.m. She then asked why her co-workers had moved her desk to the other side of the room!

Perhaps the mansion’s original owner was still arranging her sitting room to her liking.

Gallery 203—Evening Prayers

Master of San Baudelio (Spanish, active Mid 12th Century), Master of Maderuelo (Spanish), Saint Nicholas, from the Ermita de San Baudelio, Circa 1125-Circa 1150, fresco transferred to canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial and Gift of Elijah B. Martindale, 1962.600. On view in Gallery 203.

When the museum celebrated its 125th anniversary in 2016, the museum asked staff to share any strange occurrences that might have taken place in the building. A story we heard from more than one night security guard was that of the San Baudelio Chapel.

As you step into this twelfth-century space located on the museum’s second floor, you can almost feel the cold whispers of the generations of that faithful within its walls. Once located in northern Spain, this room’s style shows the rich Islamic architectural elements that have influenced Spanish visual culture.

This room, it is rumored, also holds a spirit from far away. Several members of night security say they briefly glimpsed a black hooded figure facing the chapel, which floated upwards and out through the ceiling!

A Spanish monk, perhaps, still finding solitary peace while gazing at this medieval master’s painting?

Gallery 209–Lights Out

Sir Joshua Reynolds (English, 1723–1792), Mr. Sedgwick, Circa 1757–59, oil on canvas, Gift of Mrs. James Morgan Hutton, 1964.180. On view in Gallery 209.

The spirits dwelling in the British portrait gallery seem protective rather than mischievous.

Ray, a member of the museum’s Building & Grounds team, was dusting in the gallery one morning before the museum opened. Suddenly, the lights—and strangely, the emergency lights—all flipped off.

If you’re in this gallery while reading this story, look up. There are no skylights, so the space was pitch black.

Ray was expecting to hear a voice from his radio telling him what had happened, but it was just silence and darkness. He stood for a while, but got frightened, and began to move slowly out of the gallery. Instead of walking—and run the risk of bumping into an artwork—he got down on his hands and knees to crawl toward where he thought the gallery entrance might be.

Suddenly a voice, speaking in a posh British accent, said, “Stay still, ‘twill be all right.”

Ray turned toward the voice, but he stayed in one place until the lights came back on. When he looked up, he was facing Mr. Sedgwick, a portrait by Sir Joshua Reynolds … who simply grinned at Ray in the dim light.

DeWitt entrance—Rosemary Returns

Rosemary was a beloved security guard at the museum for many years, often working at the DeWitt entrance on the ground floor.

One day, Rosemary called in sick, which was unusual. The following morning, a fellow security guard, Kim, saw her bright and early, dusting the railings on the second-floor balcony, which overlooks the front lobby. (Rosemary liked to help.)

Kim called up a cheerful “Good morning” to Rosemary but received no response. Insulted that she ignored him, he went to the staff lounge for a break, complaining about Rosemary’s rudeness.

His fellow guard looked at Kim in silent shock.

“What is it?” Kim demanded.

The other guards slowly told him that Rosemary had died in her sleep the day before.

Did you encounter a ghost during a recent visit? Let us know!