- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Roman-what? Romanesque Revival at CAM

by Franck Mercurio, Publications Editor

1/7/2026

museum history , architecture , James W. McLaughlin

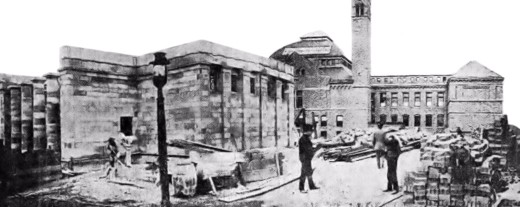

Why do parts of the Cincinnati Art Museum resemble a medieval fortress? When Cincinnati architect James W. McLaughlin designed the original Cincinnati Art Museum building (1886) and adjacent Art Academy (1887), he drew inspiration from “Richardsonian Romanesque,” a popular architectural style developed in the 1870s by Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson.

Swipe through the slideshow below to learn more about Richardson, his influence on Cincinnati architects, the fate of one of his last great works (the monumental—and long gone—Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building) and what remains of McLaughlin’s museum buildings today.

Thank you to Geoff Edwards, CAM’s archivist, who helped locate source material for this blog post.

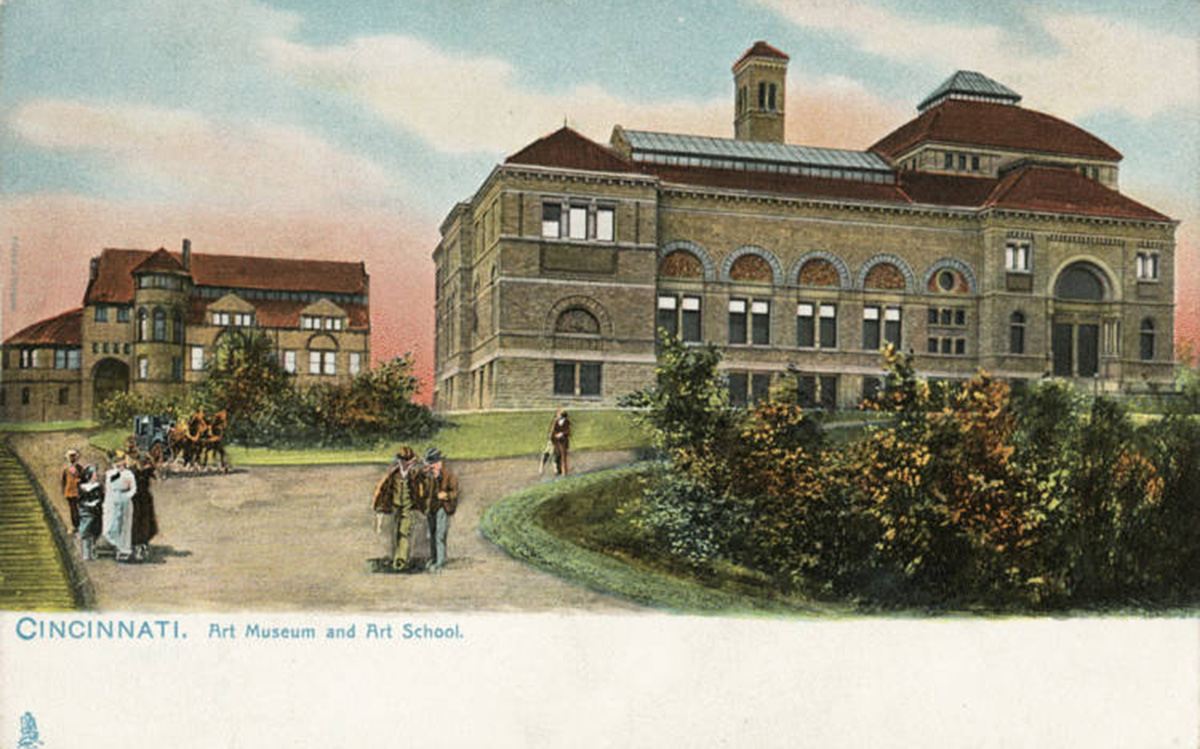

Color postcard of the original Cincinnati Art Museum and Art Academy of Cincinnati, circa 1887.

The design of the original Cincinnati Art Museum building (1886, right) and the Art Academy of Cincinnati (1887, left) reflect the influence of Boston architect Henry Hobson Richardson and his brand of Romanesque revival architecture. Designed by Cincinnati architect James W. McLaughlin (1834–1923) both buildings feature rough-cut stone masonry, rounded arches, squat columns, and minimal ornamentation—hallmarks of what architectural historians dub "Richardsonian Romanesque."

Images courtesy Wikipedia Commons (1) and (2)

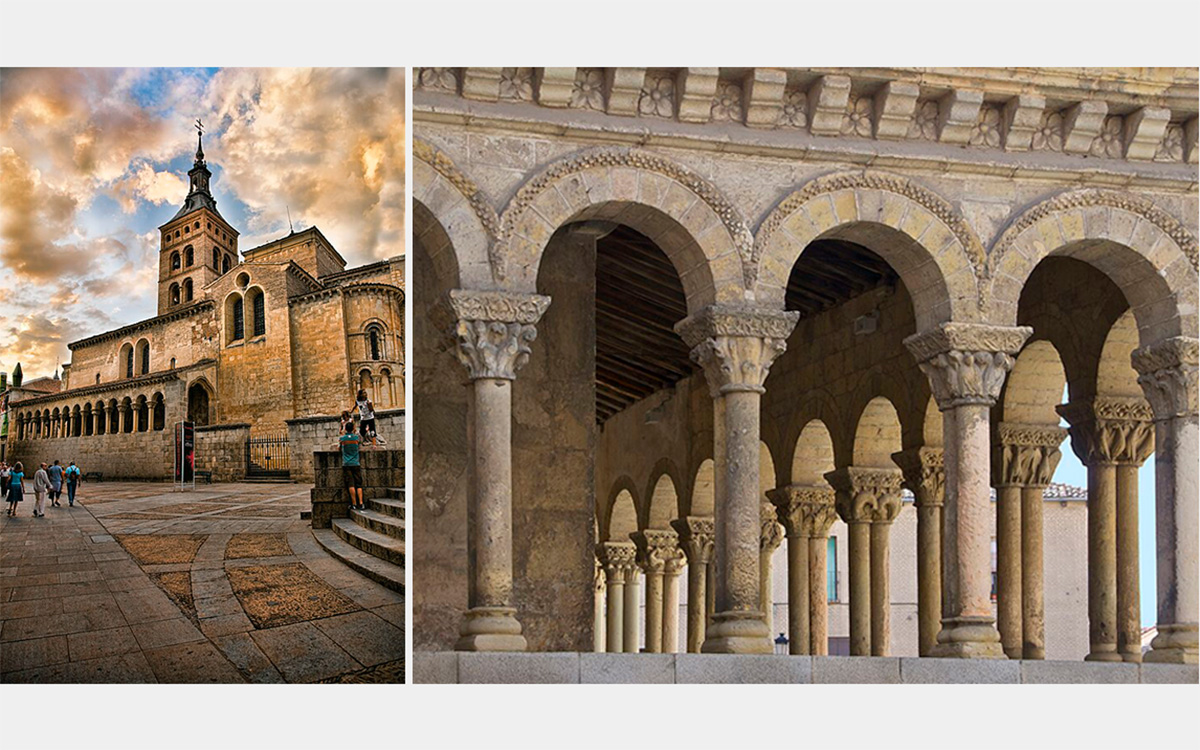

The term Romanesque ("in the manner of the Romans") took hold in the 1800s and describes the art and architecture of the early Middle Ages before Gothic dominated architectural expression across Europe. The church of San Martin in Segovia, Spain—with its heavy masonry, rounded arches, squat columns, and minimal ornamentation—provides a good example of the type of medieval architecture Henry Hobson Richardson emulated in his own designs.

Robert S. Duncanson (American, 1821–1872), Sunset on the New England Coast,1871, oil on canvas, Gift of Mrs. Gilbert Bettman, Sr., 1943.1331

On view in Gallery 108 at the Cincinnati Art Museum

Why Romanesque? Many American artists and architects in the 1800s looked to the American landscape for inspiration. Richardson's contemporary interpretation of Romanesque—particularly his use of rusticated stone and elemental forms—suggested the ruggedness of the continent's natural wonders.

“Richardson was fascinated by massive geological specimens like the smooth glacial boulders he encountered in New England and incorporated into his mature designs when he had a large enough budget," writes Martin Filler in an essay for The New York Review. "He used rough quarried stone to much the same effect elsewhere and made buildings in rural locales look like organic outgrowths of the landscape."

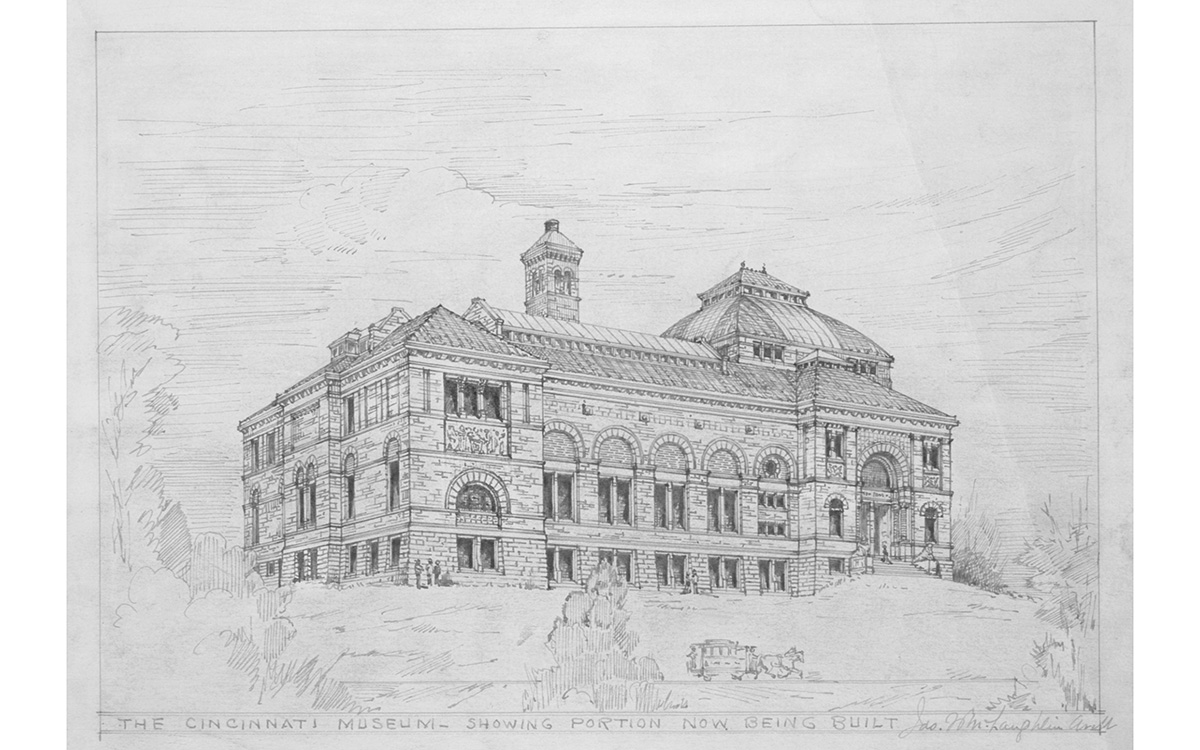

James W. McLaughlin (American, 1834–1923), View of Original Front and West Façade of Cincinnati Art Museum, circa 1885, pen and brown ink, Gift of Theodore A. Langstroth, 1979.106

This presentation rendering by architect James W. McLaughlin depicts the Cincinnati Art Museum as it originally appeared when completed in 1886, standing on a hilltop in Cincinnati's Eden Park. In the drawing, the rough-cut stone structure, designed by McLaughlin in a Romanesque revival style, appears to grow out of the hilltop itself.

Today, much of the building's exterior is no longer visible, hidden behind later additions. But you can still see the tower and the large hip-roofed “dome” and skylight that mark the Great Hall located just inside the museum’s original arched entry.

Thomas Crane Public Library in Quincy, Massachusetts (1882) by Henry Hobson Richardson

Borrowing elements from Romanesque architecture, Richardson developed a flexible architectural language to design a range of building types, including churches, residences, courthouses, libraries, and office buildings. His Crane Public Library (pictured) features Romanesque design elements: rusticated masonry (rough-cut stone), rounded arches, squat columns, and minimal ornamentation.

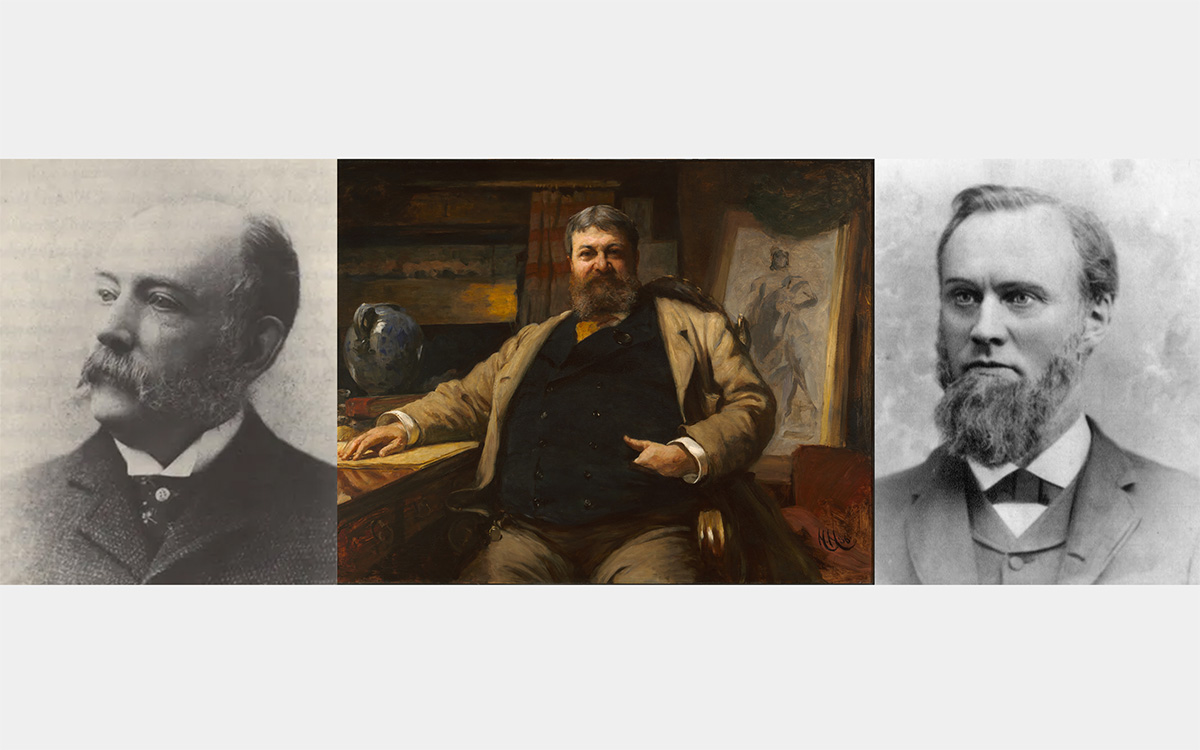

Left: James W. McLaughlin, PLCHC Digital Library, Center: Hubert Von Herkomer (German British, 1849–1914), H. H. Richardson, 1886, oil on canvas, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, R&R CC0, Right: Samuel Hannaford, PLCHC Digital Library

From the 1870s through the 1890s, architects across the United States—including James W. McLaughlin (left) and his Cincinnati rival, Samuel Hannaford (right)—emulated Richardson's brand of Romanesque revival in their own designs.

Richardson (center) died in 1886 at the relatively young age of 47, less than one month before the Cincinnati Art Museum celebrated its grand opening, and before construction began on his last major commission: the ill-fated Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building.

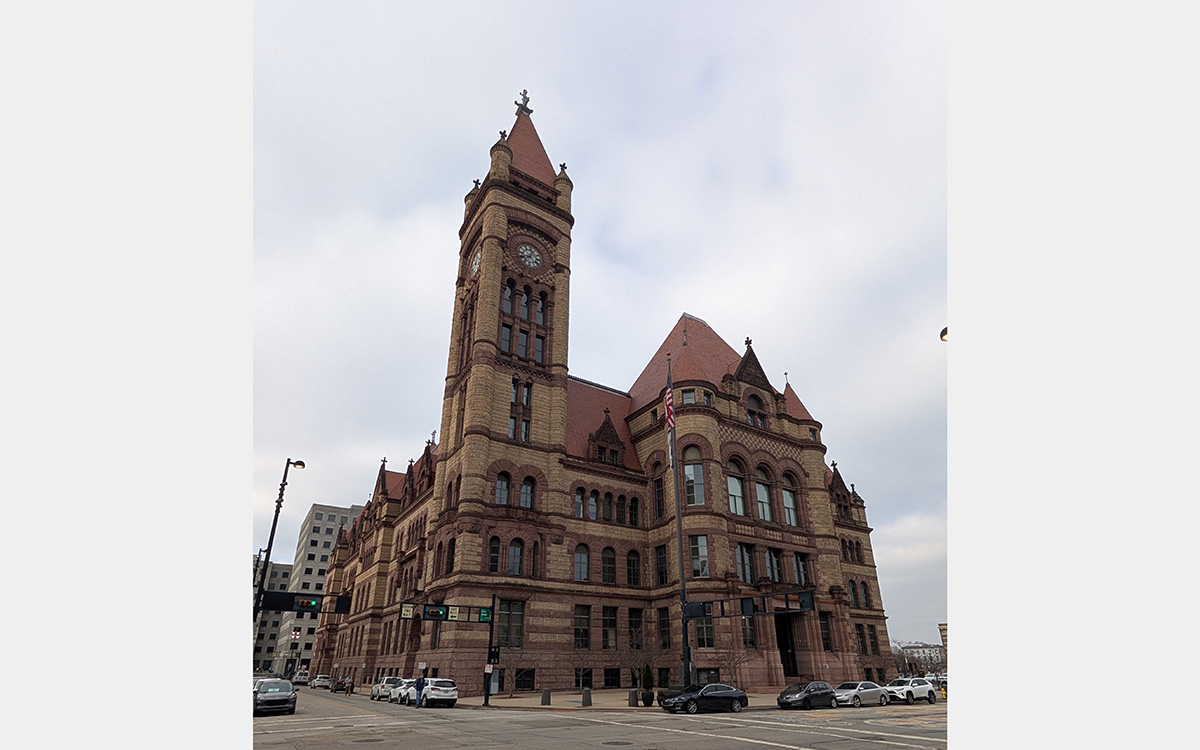

Cincinnati City Hall -- photo taken from Plum & 8th Streets

James McLaughlin's rival in Cincinnati was architect Samuel Hannaford (1835–1911). The two often vied for the city's most noteworthy commissions. Although McLaughlin won the Cincinnati Art Museum and Art Academy projects, Hannaford beat out McLaughlin for the prestigious Cincinnati City Hall commission. His design is perhaps the closest to Richardsonian Romanesque in Cincinnati.

City Hall's cornerstone was laid in 1888, two years after the opening of the Cincinnati Art Museum and one year after the opening of the Cincinnati Art Academy building.

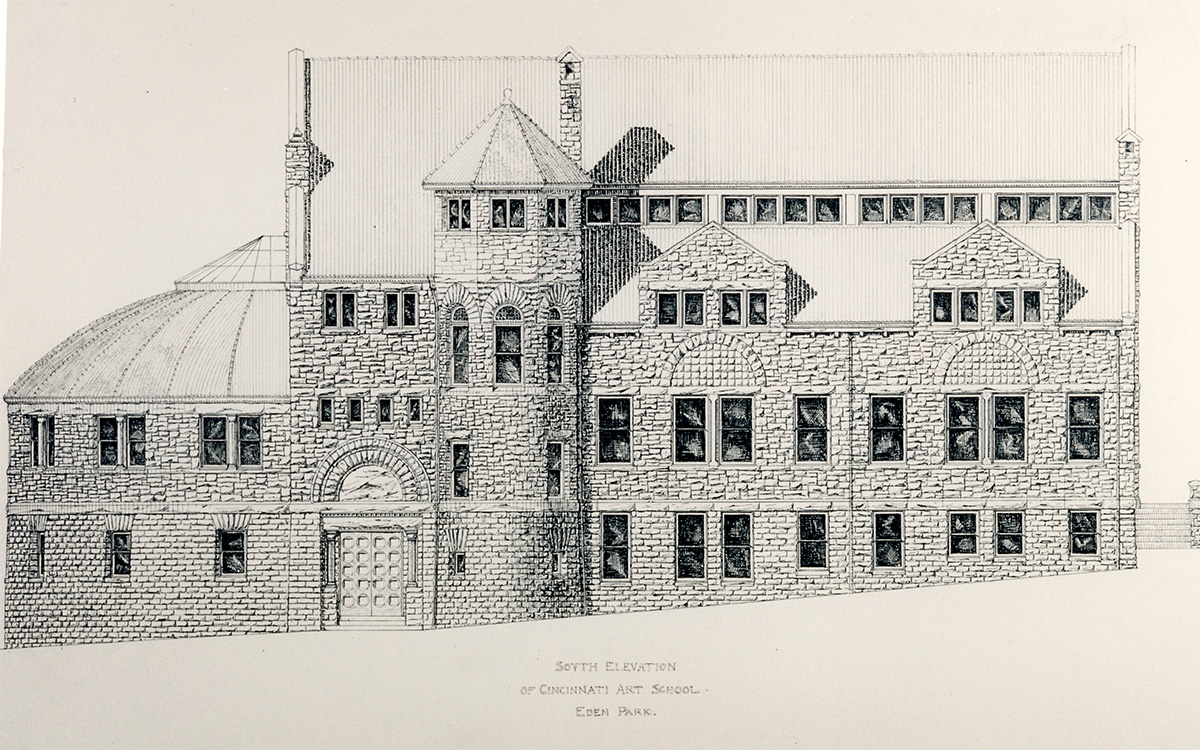

The Mary R. Schiff Library & Archives, Cincinnati Art Museum

Architect James W. McLaughlin also designed the Art Academy of Cincinnati building (1887) adjacent to the original museum building in Eden Park. (Today, it is known as the museum's Longworth Wing and houses staff offices.) The design includes the hallmarks of Romanesque revival: rusticated stone, rounded arches, stubby columns, and minimal ornamentation.

The exterior elements suggest the building's interior functions. A large, rounded arch (flanked by squat columns) marks the entryway; the turret encloses the main staircase; a curved wall and half dome define the school's lecture hall; and the tall rectangular windows bring light into the studio spaces.

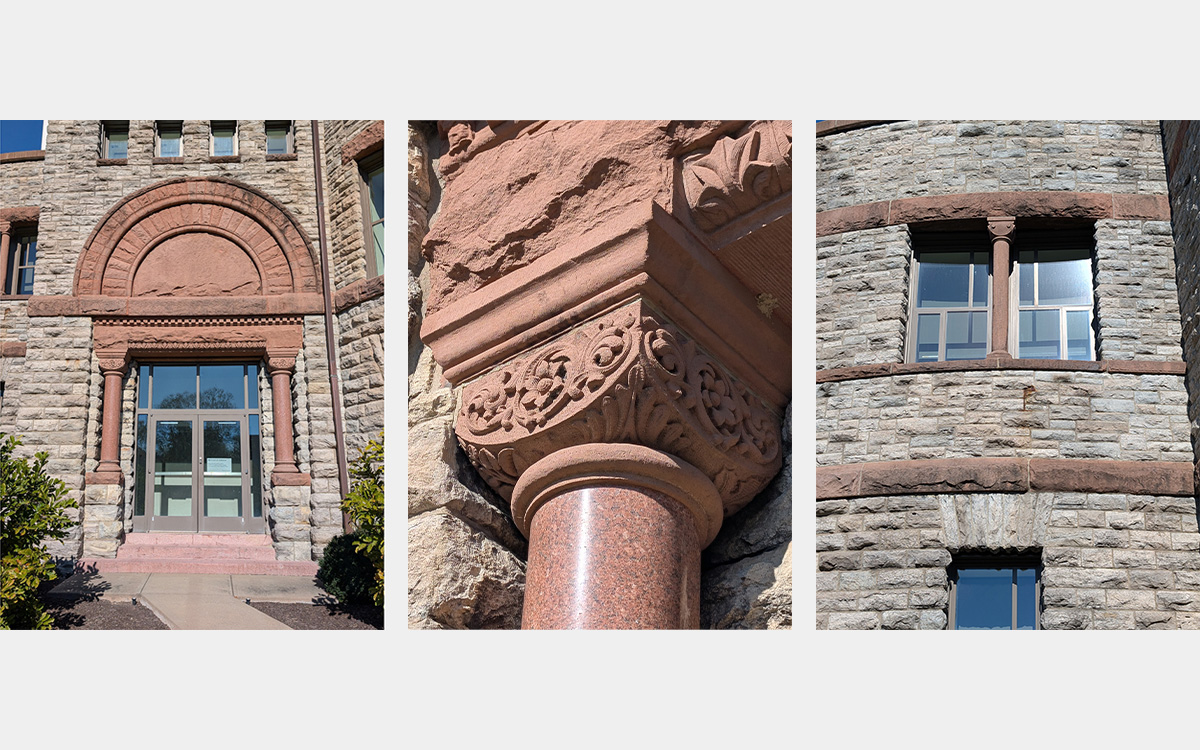

Architectural details of McLaughlin's Art Academy of Cincinnati building (1887) now known as the Longworth Wing, include ... left: massive, rounded arch over main entry supported by squat columns, center: column capital with restrained architectural ornament, right: rusticated limestone walls with bands of red granite. According to sources in the museum's Archives, the red granite was sourced from the same quarries used by Richardson for his New England buildings.

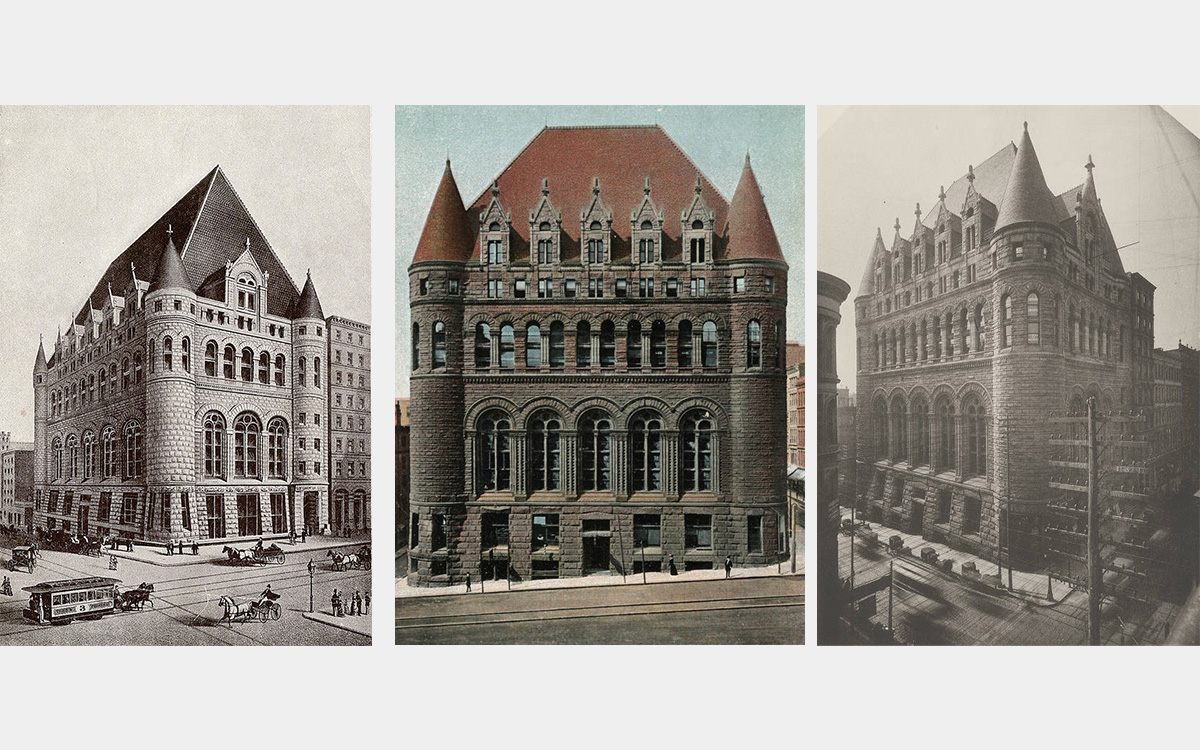

Three views of the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building (1888)

As crews completed McLaughlin's Art Academy building in 1887, construction began on Richardson's only Cincinnati commission: the monumental Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building (1888) located on the southwest corner of 4th and Vine Streets in downtown Cincinnati. Richardson was not able to see the building completed. He died two years earlier in 1886 at age 47 of kidney disease.

The massive pink granite structure—hailed as "fireproof" when it opened to fanfare in January 1889—succumbed to a devastating fire in 1911. Although the masonry walls (constructed of mammoth stone blocks) largely survived the blaze, the furnace-like heat melted the iron structural system supporting the upper floors and sent them crashing down through the building’s three-story-tall trading floor.

After hauling away the building's massive stone blocks, the Fourth & Vine Tower (better known today as the PNC tower) was constructed on the site and completed in 1913.

Richardson Memorial and Chamber of Commerce Monument in Burnet Woods Park

Soon after the fire, the Cincinnati Astronomical Society salvaged many of the stones from Richardson's Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building and hauled them first to Oakley and then to Cleves, Ohio, with the intention of building an observatory. The plan was later dropped, but some of the stones were rediscovered in 1967 by UC architecture student Ted Hammer in Cleves along Buffalo Ridge Road. A fellow student, Stephen Carter, won a design competition in 1972 to create a memorial to Richardson in Burnet Woods Park using the stones. You can still see the assemblage in Burnet Woods today, overlooking Martin Luther King Drive and UC's College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning.

Stone eagle sculpture from the Cincinnati Chamber of Commerce building in Eden Park.

Also salvaged from Richardson's Chamber of Commerce are four stone eagle sculptures that once perched on the building's dormers. Today, the eagles grace the entryway to Eden Park near the Krohn Conservatory along Eden Park Drive.

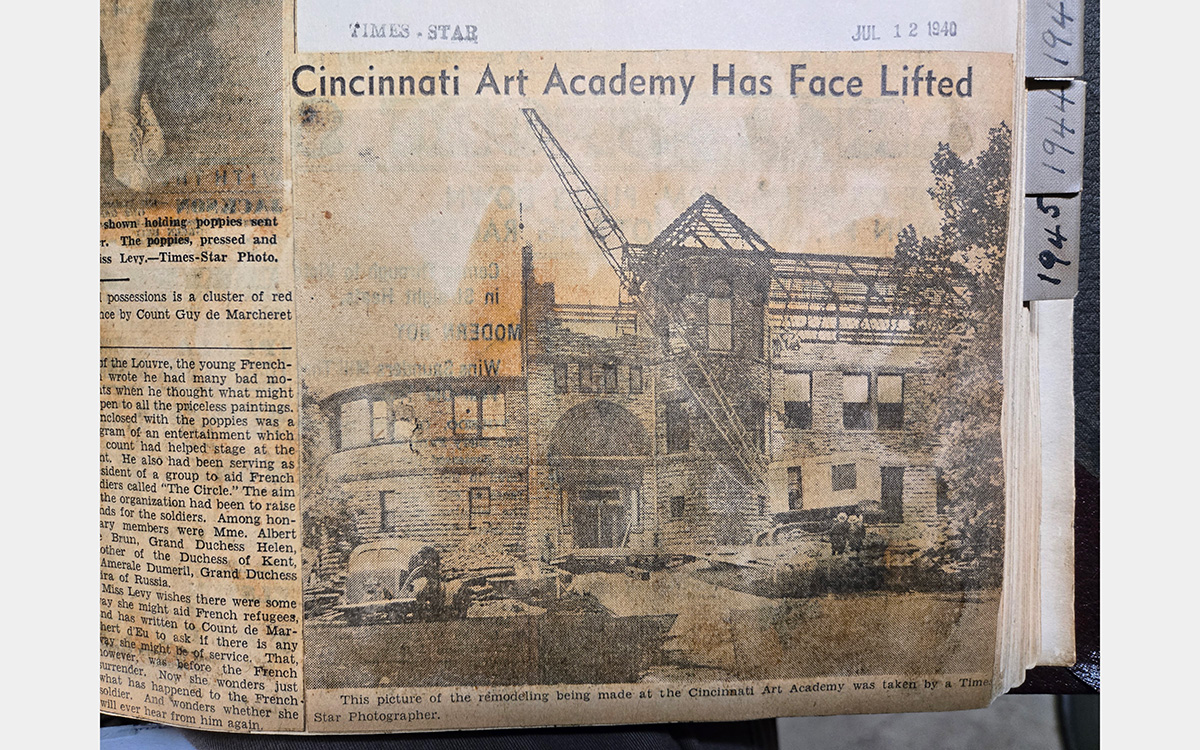

Cincinnati Times-Star, "More Daylight Assured Now for Art Academy," July 12, 1940, courtesy The Mary R. Schiff Library and Archives

More than 50 years after its opening in 1887, the Art Academy upgraded its facilities. "Elaborate improvements are being made in the Cincinnati Art Academy in Eden Park that will give this historic institution more studio rooms, more daylight and entirely new heating, electric lighting and plumbing systems," stated a Cincinnati Times-Star article in 1940. "The roof is being lowered nine and a half feet and additional skylights are being installed in such a manner that there will hereafter be daylight on both the second and third floors."

Mary R. Schiff Library & Archives, Cincinnati Art Museum

In mid-century modern fashion, the Art Academy's 1940 renovation emphasized the building's horizontal lines. Cincinnati architects Henry Hake & Henry Hake, Jr., removed the entire third floor, including the dormers, the half-dome above the lecture hall, and the top tier of the stair tower. A new rooftop structure—with more expansive windows—replaced the original elements and allowed more natural light to enter the building.

Mary R. Schiff Library, Cincinnati Art Museum

In 2005, the Art Academy left its Eden Park home of almost 120 years and moved to a new campus on Jackson Street in Over-the-Rhine. The vacant building underwent another ambitious renovation project, conceived and overseen by Cincinnati firm Emersion DESIGN, completed in 2013.

Mary R. Schiff Library & Archives, Cincinnati Art Museum

Today, you can still see some of architect James W. McLaughlin's original Art Academy building and its Romanesque revival architectural style. Now known as the Longworth Wing—named in honor of Joseph Longworth, a significant figure in the history of the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Art Academy—the building houses the museum's curators and staff. The Mary R. Schiff Library sits atop the roof inside a 2013 deconstructivist structure designed by architect James Y. Cheng of Cincinnati's emersion Design.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: