Staff Share Their Favorite Works

by Franck Mercurio, Publications Editor

2/15/2023

From greeters to grounds keepers to gallery attendants, our frontline staff experience the museum’s collections firsthand, every day. Check out these six artworks—curated by staff members in Visitor Services, Building & Grounds, and Museum Security—and discover why each represents a favorite work of art.

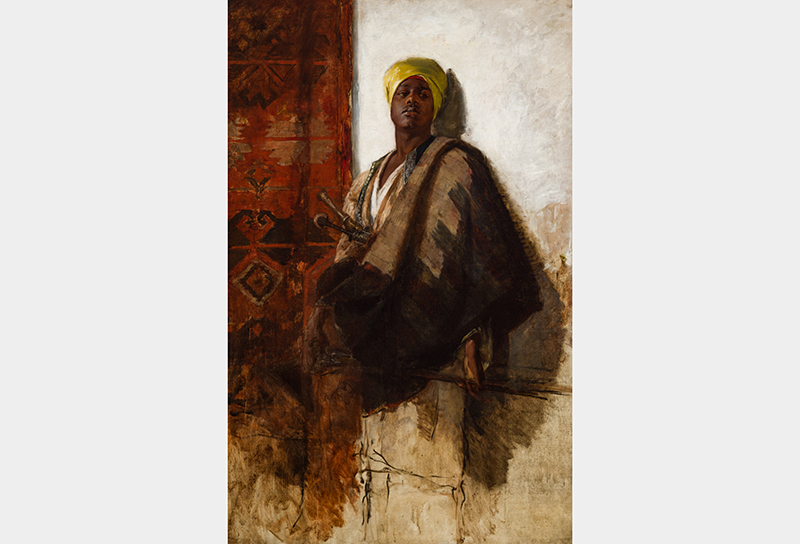

Guard of the Harem (circa 1880)

Frank Duveneck

“Being of African descent, I'm grateful for the painting to be here in this venue. It’s huge. It’s bold. You can’t miss it. [The figure] reminds me of the actor Blair Underwood; he has that actor look, that actor pose. And there’s a little sadness in his eyes. I wonder what he’s thinking. But the jaw is saying, ‘Don't mess with me,’ right? He's a figure of strength and seriousness.”

—Damon Nelson, Facilities Supervisor

Frank Duveneck (American, 1848–1919), Guard of the Harem, circa 1880, oil on canvas, Gift of the Artist, 1915.115.

The low perspective of the viewer, looking up at this large figure, makes the sitter in Frank Duveneck’s Guard of the Harem seem impressive—even intimidating. As the composition is sketchy and unfinished, the painting leaves much to the imagination.

Duveneck made several paintings of harem guards and assigned the theme to his students, but he had no interest in creating degrading narratives of harem life. Instead, the subject provided an opportunity for the artist to indulge in harmonies of rich patterns and colors while conveying a powerful masculinity.

Duveneck’s attitudes toward people of color are not fully known, but he took pride in his mother’s humanitarian efforts to help those escaping enslavement before the Civil War; later, he recalled that she provided refuge in their Covington, Kentucky, home when he was a boy.

On view in Gallery 120.

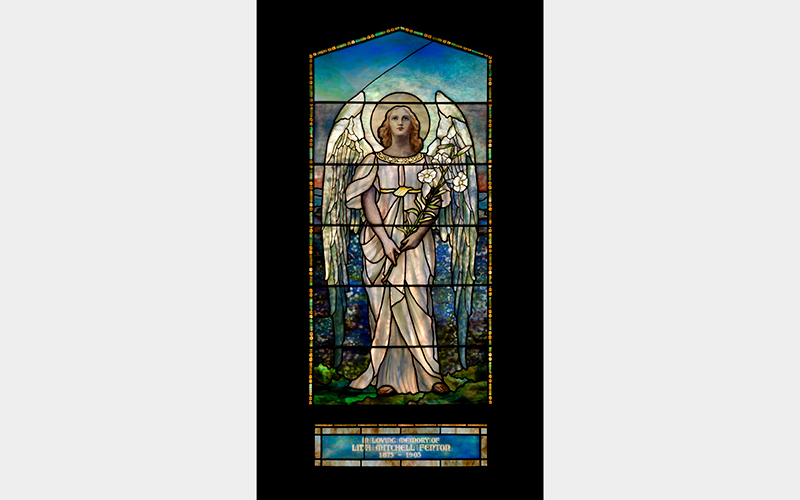

Lida Mitchell Fenton Memorial Window (1904)

Tiffany Studios, manufacturer; Joseph Lauber, designer

“I particularly like these stained-glass pieces because of how they were made—it was very unique back in the day. You can see there's actually texture in the glass. Tiffany figured out how to make it look more painterly by pooling the glass. The whole technical aspect is really cool—and it's very beautiful!”

—Lyn Redder, Gallery Attendant

Lida Mitchell Fenton Memorial Window, 1904, Tiffany Studios (American, 1900–1932), manufacturer, Joseph Lauber (American, 1855–1948), designer, glass, pigment, lead and copper foil, Museum Purchase: The Docents of the Cincinnati Art Museum in celebration of their 50th Anniversary, made possible in part through the Episcopal Diocese of Southern Ohio, 2011.16.

This angel in this stained-glass work wears a robe with a jeweled neckline. She gazes toward the sky while cradling a stalk of white lilies, often used to symbolize purity and grace. A beautiful sunrise suggests a new day or a new beginning.

The window memorializes the short life of Lida Mitchell Fenton (1871–1903), a member of a wealthy Cincinnati family, who died of tuberculosis at the age of 30 during a time when the disease was a leading cause of death.

The window’s maker, Tiffany Studios, developed a technique called “plating” where layered pieces of glass create depth and shadows and manipulate colors viewed in transmitted light. Originally, this window was one of four in St. Michael & All Angels church in Cincinnati. All four now reside at the museum.

On view in Gallery 214

Lace Mountains (1989)

Ursula von Rydingsvard

“I've always been drawn to this piece and how it really transforms the space. It can be either really intimidating or really comforting. It’s huge and kind of dark, and it can feel a little rough. But the artist puts a lot of care into her pieces. It feels natural, like something you could come across in nature and find shelter in—that’s what’s comforting.”

—Rachel Boggs, Visitor Services

Ursula von Rydingsvard (American, b. 1942), Lace Mountains, 1989, cedar and graphite, Museum Purchase: Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Endowment for Contemporary Art, 2004.1137, © Ursula von Rydingsvard Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co.

Sculptor Ursula von Rydingsvard constructed Lace Mountains by stacking cedar beams and shaping their edges through a series of cuts using a circular saw. She then toned the cut edges with a mixture of graphite and oil.

Von Rydingsvard’s work is minimal in form, yet richly and delicately articulated—and everywhere it displays evidence of the artist’s hand. But what distinguishes Lace Mountains from the work of von Rydingsvard’s contemporaries, is its extraordinary power as an image. It has a palpable human presence, while at the same time its scale and lively faceted surface evoke the elemental forces of nature.

On view in Gallery 231.

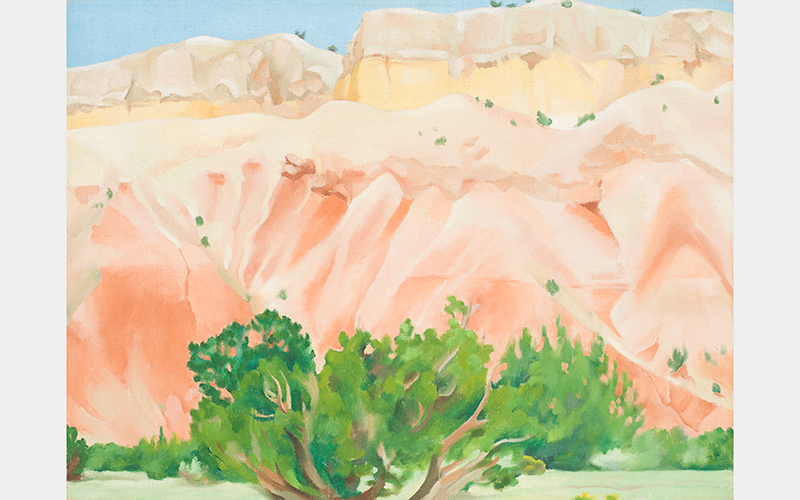

My Back Yard (1943)

Georgia O’Keeffe

“I always come back to this painting because it's so poetic, and I appreciate the spiritual and profound ways that O'Keeffe articulates her landscapes. She recodes what she is seeing through the lens of this kind of candy-colored whimsical, very beautiful, very feminine landscape and she gives a new perspective on it.”

—Kiara Galloway, Visitor Services

Georgia O’Keeffe (American, 1887–1986), My Back Yard, 1943, oil on canvas, Museum Purchase: The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment, Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. Wichgar, John J. Emery Endowment, Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Leyman Endowment, and Rieveschl Collection Fund, 2013.51, © 2023 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Georgia O’Keeffe composed My Back Yard using horizontal bands of color, placing the cooler tones at top and bottom and framing the warmer passages in the middle. The painting depicts the cliffs, as she saw them, from her summer home, Ghost Ranch, some 60 miles northwest of Santa Fe, New Mexico. Although O’Keeffe captured the recognizable contours of the landscape, she brought the cliffs up close to the surface, nearly filling the canvas with them, creating lyrical gradations of color.

O’Keeffe’s title for this picture, My Back Yard, is both an ironic and affectionate commentary on the subject. While the image defies the stereotype of the suburban back yard, the title denotes the artist’s intense attachment to the place she experienced every day in the American Southwest.

On view in G211.

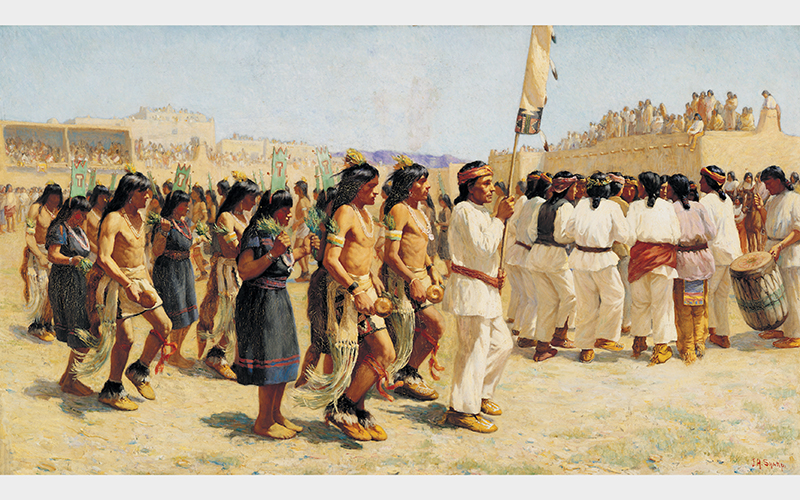

The Harvest Dance (1893–94)

Joseph Henry Sharp

“This painting brings me back to Massachusetts, where I’m from, in Mashpee on the Cape. Where we lived, the Wampanoag Indians have a powwow, and they do all the festival dances. I've been involved with Wampanoag culture ever since I was young. My friends—and my new wife and my stepsons—are Wampanoag. So, when I walk by the painting, I’m like “Oh, this reminds me of home, and it reminds me of the kids.”

—Dale Cochran, Buildings & Grounds

Joseph Henry Sharp (American, 1859–1953), The Harvest Dance, 1893–94, oil on canvas, Museum Purchase, 1894.10.

In 1893 Cincinnati artist Joseph Henry Sharp visited Taos, New Mexico, for the first time. When he returned to Cincinnati, the artist brought home The Harvest Dance and displayed it at the Fourth Annual Exhibition of the Cincinnati Art Club. Impressed with the painting, the museum’s trustees purchased the work.

The artist described the harvest ceremony, depicted in the painting, as “a striking scene of gorgeous color.” Harper’s Weekly from October 14, 1893, quoted Sharp as saying:

“The brilliant sunlight illuminates the gaudy trappings of the dancers. Rows of gayly dressed Apaches, Navajos, and Pueblos on horseback encircle in quiet dignity the enthusiastic actors, while a little farther off the whole seen is framed in the gleaming walls of the white and yellow house.”

On view in Gallery 122.

Alexander the Great and the Fates (circa 1667)

Bernardo Mei

“I tell people, ‘Instead of looking at the art, look into it,’ because by looking into the art, you see through the artist's eyes, you see what he sees and what he believed at the time when he lived. It's like a letter going through time long after the artist is gone. In this painting, he’s trying to tell viewers that you cannot control your final destiny.”

—George Austin III, Gallery Attendant

Bernardino Mei (Italian, 1612–1676), Alexander the Great and the Fates, circa 1667, oil on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1988.167.

Theatrical, exuberant, and marked by strong contrasts of light and shadow, Alexander the Great and the Fates, exemplifies many of the characteristics of the Baroque style. Bernardino Mei created this monumental and complex painting, filled with allegorical figures, to commemorate the death of another Alexander, Pope Alexander VII, who died in 1667.

On the left side of the painting, the artist depicts two of the three Fates as they spin and measure the thread of Alexander the Great’s life. The third Fate—responsible for cutting the thread and ending his life—grapples with our Greek hero. Meanwhile, Fame, with her long trumpet, reassures Alexander that, in spite of his death, his memory will endure, and he will remain triumphant over Time (the winged figure underfoot).

On view in Gallery 202.