- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

American Painting Collection: Framed!

by Julie Aronson

4/11/2016

curatorial , frames , Julie Aronson , American Painting & Sculpture , Frank Duveneck , Georgia O’Keeffe , Arts & Crafts

When giving tours of the American paintings collection, I sometimes field more questions about frames than I do about the paintings. A frame can subtly, or not so subtly, change our perceptions about the work of art it surrounds. Some frames rival the painting for our attention while others seem to disappear. Neither is bad in my view, but the effect requires consideration when making decisions about a frame. One thing I have learned over the years is that how one feels about a frame is a matter of taste: the curator’s opinion is just one of many. One of my favorite stories is about the acquisition of Duveneck’s painting Siesta, which came to us in a bequest several years ago in a carved and gilded frame heavily encrusted with an abundance of fruit and leaves. One of our patrons, an artist herself, shocked me when she opined, “Surely you are not keeping that gaudy frame!” Not only do I adore this frame for its great beauty and craftsmanship, but in my view it is a perfect companion for a painting that celebrates the sensual pleasures of country life.

While you might go to a frame shop and make a selection because it suits your décor, the curator has other criteria to consider. Knowledge about the history of frame design, the artist’s framing preferences and other types of documentation inform our decisions about whether to retain a frame as well as what kind of frame would be appropriate for a painting. All evidence suggests that the frame on Siesta is original to this picture, including its date to the time when the painting was made and its probable Italian origins (Duveneck painted Siesta in Florence). That this frame is similar to those on several other Duveneck paintings makes a strong case for the artist having selected it.

“Is the frame original?”—a frequently asked question—is more complicated to answer than most realize. The original frame is the first frame that the painting acquired after its completion. This begs the question of who chose the frame: was it the artist, a dealer or the painting’s first owner? Moreover, does original equal good? (And, concomitantly, does unoriginal equal bad?). The museum values the original frame when, both historically and aesthetically, it forms a happy marriage with the painting. In the past, antique frames were not valued as they are today and sometimes historically appropriate frames were discarded. The preference for worm wood and linen liners in the mid-20th century relegated many an elaborate gilded confection to the dust bin. While now we spend thousands of dollars on frame conservation, in earlier days a frame with busted corners and a soot-caked surface was replaced, usually with an inexpensive alternative. Now I often find myself despairing over the frame selections of my forebears; when trying to decide how to reframe a picture I run to the Archives in search of gallery photographs that include the painting in its former frame hanging on the wall.

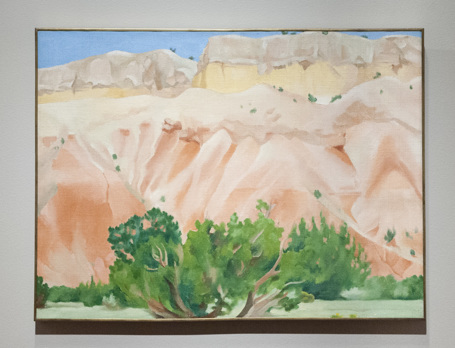

In my sixteen years here at the CAM, no frame has generated more conversation than that of Georgia O’Keeffe’s My Backyard of 1943, which we purchased at auction in 2013. When this painting was consigned to sale it was housed in a silver Arts & Crafts style frame from the early 20th century, as one would find on an American Impressionist picture. I was surprised to discover than under this frame was a brass strip attached to the sides of the canvas with screws. Sending photos to my colleague at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, I learned that this minimal metal frame was of a type that O’Keeffe commissioned from a framer for some of her paintings. Visually, it provides only a narrow line of separation of the image from the surrounding wall; the mountain landscape fills the frame, pushing against the edges. Feelings about this frame run very strong, frequently negative, but I feel confident that this is the way O’Keeffe wanted us to experience her picture and believe that it is the museum’s responsibility to respect the artist’s wishes when known. Although at first I was unsure how I felt about the frame, especially as it emphasizes the painting’s small size, I have grown to appreciate her aesthetic vision. I particularly like the warmth the finish gives the picture. Come visit the Art Museum to see what you think.

Image Credit: Frank Duveneck (1848–1919), Siesta in its period frame, 1886, oil on canvas, Bequest of Mary O’Brien Gibson in memory of her parents, Cornelius and Anna Cook O’Brien, 2007.68

Image Credit: Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), My Back Yard in frame selected by the artist, 1943, oil on canvas, Museum Purchase: The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, Fanny Bryce Lehmer Endowment, Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. Wichgar, John J. Emery Endowment, Mr. and Mrs. Harry S. Leyman Endowment, and Rieveschl Collection Fund, 2013. 51. ©2016 Georgia O’Keeffe Museum / Arists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: