Celebrating Women's History Month

by Cincinnati Art Museum

3/1/2023

March is Women’s History Month—commemorating and encouraging the study, observance, and celebration of the vital role of women in history.

Did you know the Cincinnati Art Museum was founded by women? In the late nineteenth century, public art museums were still very much a new phenomenon, especially as far west as Cincinnati. However, during the 1800s, the city had become one of the most important centers of art and design in the Midwest, and the establishment of an art museum seemed to be the next logical step for many. This included the members of the Women’s Art Museum Association (WAMA), which was established in 1877 to promote the benefits such an institution would provide for the community. Thanks in large part to their tireless efforts, support for an art museum grew steadily, and in 1881 a public subscription attracted enough contributions to secure the project’s future.

Hamra Abbas (b. 1976)

Hamra Abbas (Pakistani, b. Kuwait, 1976), Garden 2, 2022, marble, lapis lazuli, serpentine, jasper, pink calcite, Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art. See this artwork in Gallery 143.

In Garden 2, Hamra Abbas has created a disrupted landscape in tessellated stone. Historically and in Muslim-majority cultures, the garden is visualized through botanical embellishments on architecture and decorative arts. These motifs literally or symbolically reference Qur’anic scripture, where the Garden of Paradise is full of trees, flowers, plants, and rivers. Abbas derives inspiration from the architecture of Lahore, Pakistan, to create works that contemplate the garden as a utopia, an idyllic landscape.

To create these pietra dura (marble inlay) works, Abbas begins with drawings to scale that she numbers to indicate stone selection. She then chooses slabs of stone based on tonality, which are sliced, cut, and shaped by hand before careful placement and final polishing. Marble inlay has a long history in both Europe and South Asia. Within the Mughal Empire, the Taj Mahal is the quintessential representation of its use, yet the technique is also found at the Lahore Fort, among other locales. Abbas has pulled this historic practice into the present to create an expansive, integrated composition.

Listen to a museum volunteer discuss Abbas’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on January 17, 2023.

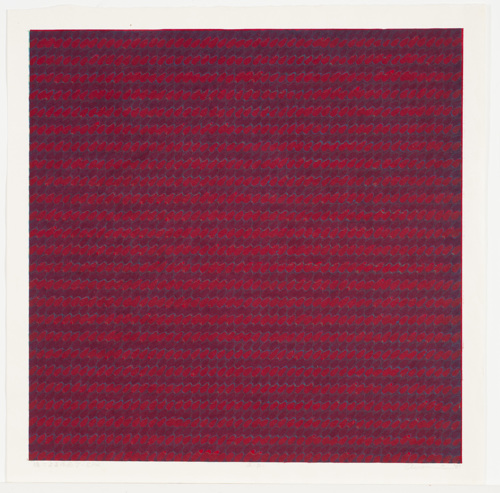

Yoshida Ayomi (b. 1958)

Yoshida Ayomi (Japanese, b. 1958), Work by Line V-EPK, 1981, color woodcut, The Howard and Caroline Porter collection, 1990.1172. See this artwork in Gallery 213.

Yoshida Ayomi is a Tokyo-based printmaker, installation artist, and designer. Daughter of Yoshida Hodaka (1926–1995) and Yoshida Chizuko (1924–2017), she is the third generation of the Yoshida family of printmakers. Ayomi has spent four decades pushing the boundaries of woodcut, the Asian medium deeply rooted in Buddhism, creating a fresh contemporary style that bears little resemblance to her family’s work, let alone traditional Buddhist prints. Unable to locate supplies for screen prints upon her return to Japan, she turned to the family tradition of woodcut prints.

Deborah Butterfield (b. 1949)

Deborah Butterfield (American, b. 1949), Horse No. 1, 1983, red mud, sticks, metal armature, Henry Meis Endowment and various funds, 1984.94, © Deborah Butterfield/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. See this artwork in Gallery 104.

Deborah Butterfield makes her sculptures from found materials such as scrap metal, mud, clay, and twigs. Each embodies a particular personality. Whether gentle, frightened, funny, or capricious, each can be understood as a self-portrait of the artist, an exploration of attitudes and feelings. In this sculpture, Butterfield uses metal, wood, and mud to create the contours of a horse. Twigs stick out from the frame and remind us that the work is composed of debris. Yet the sum of the assembled materials provides a majestic presence.

Butterfield began creating naturalistic horse sculptures in the 1970s, when many artists turned away from lifelike representation and toward Conceptual art. Butterfield was born on the same day as the seventy-fifth running of the Kentucky Derby, which she claims to be the inspiration for her tendency to create horses.

Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012)

Elizabeth Catlett (American, 1915–2012), Phillis Wheatley, 1973, bronze, Museum Purchase: Dr. Sandy Courter Memorial Fund, Lawrence Archer Wachs Fund, A. J. Howe Endowment, Henry Meis Endowment, Phyllis H. Thayer Purchase Fund, Israel and Caroline Wilson Fund, On to the Second Century Endowment, 1999.215, © Catlett Mora Family Trust/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. See this artwork in Gallery 211.

In 1973, at a conference on women poets, writer Margaret Walker suggested to Elizabeth Catlett that she make a sculpture of Phillis Wheatly, the first published Black poet. Wheatley was born in Senegal and sold into slavery as a child. The white Wheatley family of Boston purchased her and provided her with a classical education. After the publication in 1773 of Wheatly’s Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral, the family emancipated her. She went on to author about 145 poems and corresponded with George Washington and other leading statesmen.

Catlett used the only known portrait of Wheatley, the engraved frontispiece to her book, as a guide. She simplified the details of Wheatley’s clothing to produce an image of the poet that is both iconic and contemporary. She also abstracted Wheatley’s features to resemble an African mask, which contributes to the stoic appearance. These subtleties are significant both to Catlett’s interests as an artist and to Wheatley’s legacy.

During her graduate studies at the University of Iowa, Catlett was influenced by painter Grant Wood, whom she admired for his belief in the artist’s social responsibility. Catlett drew on a range of creative traditions, including the work of the Mexican muralists, the African Art collection at the Barnes Foundation, and the ar of the European masters, including Van Gogh. Invigorated by the Black Power and feminist movements, she specialized in images of empowered women, often Black or Mexican throughout her career.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Catlett’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on May 19, 2020.

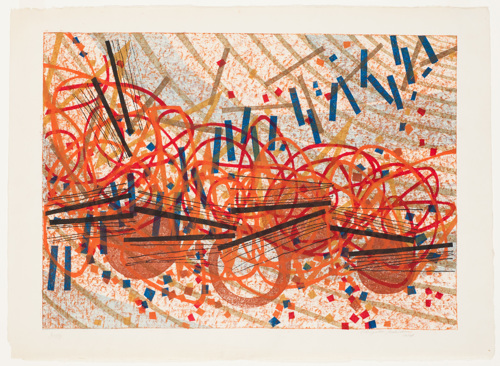

Yoshida Chizuko (1924–2017)

Yoshida Chizuko (Japanese, 1924–2017), Jazz, 1954, color woodcut, The Howard and Caroline Porter Collection, 1990.1174. See this artwork in Gallery 213.

Yoshida Chizuko (née Inoue) was a modernist artist whose work reflects the changes in Japanese art following World War II. She is noted for providing a connective link between modern art movements—including Abstract Expressionism, Op Art, and Minimalism—with traditional Japanese imagery. She was an established artist before she married Yoshida Hodaka (1926–1995) in 1953. Her earliest prints, from the mid-1950s, with restless abstract shapes mimicking the energy of musical instruments, reflect her love for music.

Helen Frankenthaler (1928–2011)

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928–2011), Rock Pond, 1962–63, acrylic on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia Irwin Memorial, 1969.11, © 2016 Helen Frankenthaler Foundation, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. See this artwork in Gallery 231.

Abstract Expressionism became legendary for paintings of monumental scale, bold gestures, and decisive action. A mythic, heroic masculinity, akin to James Dean in the movies, surrounded the movement’s male artists, who via media hype, attained iconic stature. This veneration of machismo, epitomized by the image of a muscular Jackson Pollock making his celebrated drip paintings, left little room for the women of this movement.

Experimenting with Pollock’s idea of pouring paint onto a canvas on the floor, Helen Frankenthaler invented a technique that became highly influential: she stained the raw canvas with washes of brilliant color, achieving a delicate equilibrium between accident and control. Typically, as in Rock Pond, her large organic forms evoke the experience of nature and landscape. The museum acknowledged Frankenthaler’s achievement by acquiring Rock Pond just a few years after its completion.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Frankenthaler’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on January 1, 2021.

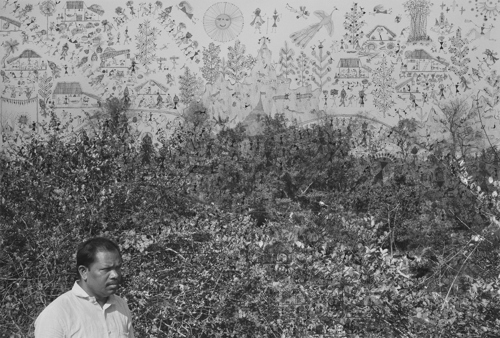

Gauri Gill (b. 1970)

Gauri Gill (Indian, b. 1970) and Rajesh Vangad (Indian, b. 1975), Bohada, from the series Fields of Sight, 2021, inkjet print with applied acrylic paint, Museum Purchase: Carl and Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art, 2022.45 © Gauri Gill. See this artwork in Gallery 143.

Photography has been a means of self-representation and marginalization within Indian society, as well as a tool for European colonial powers seeking to control the subcontinent. New Delhi-based artist Gauri Gill uses her camera to explore new, democratic visual languages for the medium.

Bohada is a collaboration between artists Gauri Gill and Rajesh Vangad (b. 1975), the latter a member of a marginalized indigenous community called the Warli. Gill photographed Vangard standing near his home village in Maharashtra, western India. Then—using the themes and geometric style associated with Warli art—Vangad created an intricate and expressive painting on the surface of Gill’s photograph. The result is an image of one place that carries two ways of experiencing and visualizing the world.

Vangad’s painting depicts the Bohada festival, where local communities create masks and enact scenes from Hindu epics and tribal myths. Look closely and you will see a masked figure representing Suraj Dev, or the sun, illuminating detailed episodes from the present-day performance of a traditional festival—from community members making and donning masks to a winding dance procession.

Sophie Guillemard (1780–after 1819)

Sophie Guillemard (French, active 1801–1819), Portrait of a Young Lady Distracted from Her Music Lesson, 1801, oil on canvas, John J. Emery Fund, 1917.369. See this artwork in Gallery 225.

A seated girl turns her head to meet the gaze of the viewer, exuding a quiet confidence, while her hands rest upon a song book in her lap. In 1801 this painting was included in the Paris Salon, the most important annual exhibition of contemporary art at the time. Sophie Guillemard exhibited portraits and history paintings at 16 subsequent Salons—one of more than 200 female artists to do so in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. In recent years, scholars have reattributed to female artists many paintings of the period, including this one, once thought to have been made by famous male contemporaries such as Jacques-Louis David and Jean-Baptiste Regnault.

The clean lines and restrained ornament of the chair and the girl’s dress hint at Egyptian and Roman antiquity and reflect a set of design preferences known as the Empire style that took hold in Napoleonic France (circa 1797–circa 1814).

Katharina van Hemessen (1528–after 1587)

Jan van Hemessen (Flemish, 1528–after 1587) and Katharina van Hemessen (Flemish, b. 1527), Altarpiece with Scenes from the Old and New Testaments (the Tendilla Retablo), 1550s, oil on panel, Fanny Bryce Lehmer and John J. Emery Endowments, 1953.219. See this artwork in Gallery 204.

A team of Flemish artists, created this elaborate altarpiece, composed of 13 painted panels set into a carved wooden frame, for a wealthy patron from Tendrillo, Spain (located 50 miles from Madrid).

Each panel depicts a scene from the Bible and arranged to convey religious concepts. The scenes on the left side of the opened altarpiece (including Adam and Eve, the Nativity, and the Lamentation), emphasize physical aspects of Christian history, while those on the right (the Sacrifice of Isaac, the Baptism of Christ, and the Ascension) portray more spiritual themes. The three scenes in the center (the Crucifixion, Saint Jerome at Prayer, and the Meeting of Mary and Elizabeth) represent the fusion of the physical and the spiritual. The Annunciation, depicted on the exterior of the two wings, was visible to the congregation when the altarpiece was closed. The Virgin Mary is represented on the left wing and the angel Gabriel on the right, in keeping with this altarpiece’s overall division of “physical” and “spiritual” realms.

At least three artists seem to have contributed to the execution of this complex project. Artist Jan Sanders van Hemessen probably designed the overall project, which was completed by members of his Antwerp studio, including his daughter Katharina van Hemessen. The wooden frame was apparently made in Spain specifically to house the paintings imported from Flanders.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss van Hemessen’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on September 3, 2020.

Angelica Kauffman (1741–1808)

Angelica Kauffman (Swiss, 1741–1808), Abraham Banishing Hagar and Ishmael, 1792, oil on canvas, The Edwin and Virginia H. Irwin Memorial, 2021.43. See this artwork in Gallery 210.

Three full-length figures clad in primary colors are lyrically composed in a stark setting. The Old Testament patriarch Abraham is banishing Hagar—his wife Sarah’s maid—and their fourteen-year-old son Ishmael. Sarah and young Isaac, her son with Abraham, look on from the house. The idea of unjust exile and the responsibilities of Hagar would have resonated with Polisssena Turinetti di Priero, who commissioned this painting in the same year she moved her family to Florence from their ancestral seat in Turin in opposition to the French occupation of that city.

Made at the pinnacle of her career, this is one of only a few religious paintings by Angelica Kauffman. Kauffman achieved success and fame as an artist and intellectual from an early age, moving easily between Italy and England. She was a founding member of the Royal Academy in London, and her time and talents were sought after by an illustrious international clientele.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Lebrun (1755–1842)

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Lebrun (French, 1755–1842), Portrait of a Young Woman Playing a Lyre, late 1780s, oil on canvas, Gift of Emilie L. Heine in memory of Mr. and Mrs. John Hauck, 1940.981. See this artwork in Gallery 207.

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Lebrun was a prominent French portraitist whose career spanned the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. She was a favorite painter of Queen Marie Antoinette and had to flee France amid the turmoil of the French Revolution. Working throughout Europe, Vigée Lebrun continued to paint portraits of aristocrats and prominent society figures, and was elected to art academies in 10 cities, an impressive achievement.

Vigée Lebrun often painted her sitters in Neoclassical dress and settings, evoking the arts and culture of Greco-Roman antiquity, which had a profound influence on European art, architecture, literature, and music during this period. In this painting, a young woman wears a Greek-inspired white gown and holds a lyre. Vigée Lebrun may have painted her patron or model in the guise of Erato, the muse of lyric poetry, whose primary attribute is a stringed instrument.

Ann Lowe (1898–1981)

Ann Lowe (American, 1898–1981), Dress and Belt, 1935–38, silk, Anonymous Gift, 1999.811a-b. This artwork is currently not on view.

Born in Clayton, Alabama, in 1898, Ann Lowe was a Black fashion designer, but few know her name. In fact, in 1964, the Saturday Evening Post ran an article titled “Ann Lowe: Society’s Best Kept Secret,” and she was just that. Unjustly kept a secret because she was Black, her name was passed surreptitiously among the crème-de-la-crème of society, but never acknowledged outwardly. Even today, few know that she designed Jacqueline Bouvier’s wedding dress for her marriage to John F. Kennedy in 1953. When Lowe arrived in Newport, Rhode Island, to deliver the gown, the staff refused to allow her to enter by the front door, telling her to go to the back. Insistent, Lowe stated she would take the dress home with her if she was not allowed in the main entrance.

Having learned to sew from her grandmother and mother, Lowe attended design school in New York where she was segregated from the other students. She won the respect of her instructors, however, because of her exceptional workmanship. Lowe opened her first salon in Tampa, Florida. By the late 1920s, she had moved to New York where she worked on commission. In 1950, she opened Ann Lowe Gowns, making couture dresses.

The museum now holds four dresses by Lowe. Three were given by an anonymous donor, including this piece. A Lowe trademark—the flower—is shown here in her choice of fabric, printed with a Japanese-like version of a chrysanthemum. Each of the other Lowe pieces in the museum’s collection also incorporate a flower into the design.

Elizabeth Nourse (1859–1938)

Elizabeth Nourse (American, 1859–1938), The First Communion (La Première communion), 1895, oil on canvas, Museum Purchase: John J. Emery Endowment and Bequest of Mr. and Mrs. Walter J. Wichgar, 2013.13. See this artwork in Gallery 119.

In 1894, Cincinnati native Elizabeth Nourse visited the French region of Brittany for the first time. In the village of Saint Gildas-de-Rhuys, she roomed at the convent of the Sisters of Charity of Saint Louis and made the sketches that she developed into this composition. After its French debut, the painting traveled to exhibitions in Chicago, Philadelphia, Berlin, and Pittsburgh, where critics lauded the tour-de-force in the handling of the white dresses. Also noteworthy are the subtlety with which the artist explored the relations of black, white, and gray and the arrangement of simple shapes. Varied textures enhance the painting’s visual interest; the filminess of the gowns contrasts with the thick impasto she used for the sashes.

Susanna Hinkle, a prominent Cincinnatian, purchased The First Communion and loaned it to the museum from 1919 to 1935. She then donated it to the Cincinnati Catholic Women’s Association for its headquarters. To support its charitable mission and share the painting with the public, the Association sold it to the museum in 2012.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Wai’anapanapa Black Sand Beach, March 1939, gelatin silver print, Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum. See this artwork in Georgia O’Keeffe, Photographer, now through May 7, 2023. Ticketed. Free for members.

In 1939, Georgia O’Keeffe accepted an invitation from an advertising company to go to Hawaii to produce paintings for the Hawaiian Pineapple Company. She kept these photographs for the remaining five decades of her life. The “Hawaii snaps,” as she referred to them, capture subject matter that is quintessentially O’Keeffe—dramatic landforms and perfect flower blooms.

In many of her letters home from Maui, O’Keeffe described her desire to photograph the island’s landscape and vistas. “The black sands of Hawaii—have something of a photograph about them,” she wrote. Perhaps the artist was responding to the chromatic simplicity of lacey white sea foam on black sand. Yet, there is also a notable relationship between O’Keeffe’s attraction to reframing and the constantly changing, expressive compositions created by nature as the edges of waves skim over the beach. Here, she seems to explore exactly that visual potential.

Maria van Oosterwijck (1630–1693)

Maria van Oosterwijck (Dutch, 1630–1693), Flower Still Life, 1669, oil on canvas, Bequest of Mrs. L.W. Scott Alter, 1988.150. See this artwork in Gallery 205.

In seventeenth-century Holland, intense interest in exotic flowers contributed to the popularity of paintings like this. These paintings functioned on several levels: as colorful decoration, scientific curiosities, and moralizing reminders of the passage of time (cut flowers will soon wilt and fade). They also demonstrated the artist’s powers to preserve otherwise ephemeral beauty.

Maria van Oosterwijck achieved the heights of her profession, being patronized by royal courts across Europe. She trained in Utrecht, and by 1671, was most likely established in Amsterdam. She worked slowly; less than two dozen paintings by her survive today. That she was unmarried and among the most successful painters of her generation—a double rarity for a woman of her time—has inspired speculation about her life, which was even novelized in the nineteenth century.

This is one of her earliest dated paintings, and the large signature on the edge of the table reveals a confident, established artist.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Oosterwijck’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on May 7, 2020 and this CAM Access episode posted on June 28, 2020.

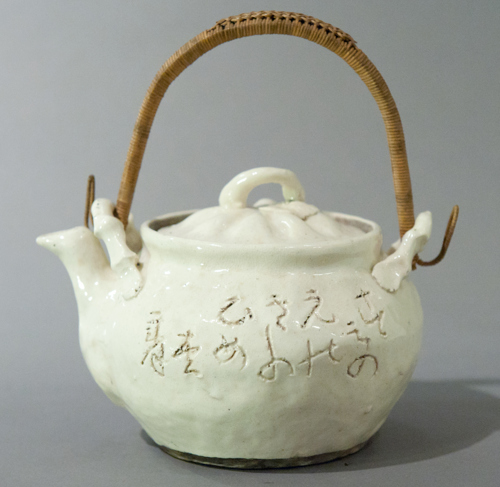

Rengetsu Ōtagaki (1791–1875)

Teapots, 19th Century; circa 1875, Rengetsu Ōtagaki (Japanese, 1791–1875), ceramic, Gift of the Rookwood Pottery, 1898.27–28. See these artworks in Gallery 151.

Rengetsu Ōtagaki, originally from a samurai family, was adopted at an early age by the Ōtagaki family. In 1823 she became a Buddhist nun and took Rengetsu (“Lotus Moon”) as her name. Her broad interests led her to become one of the greatest Japanese poets, potters, painters, and calligraphers of the nineteenth century. The unique spirit of her work came from a life spent in deep meditation on the illusory nature of existence. Her ceramic works became so popular that they continued to inspire many followers after her death and led to the rise of Rengetsu-ware.

Rengetsu often adorned her ceramic works with her own poems written in her elegant kana script. The museum’s two teapots, one white and one brown, fully demonstrate her combined arts of poetry, calligraphy, and simple down-to-earth design. Both teapots were collected by Kitaro Shirayamadani in Japan for Rookwood Pottery and given to the museum in 1898.

Emmy Roth (1885–1942)

Tea and Coffee Service (7 piece), circa 1930, Emmy Roth (German, 1885–1942), silver and ivory, Museum Purchase: Decorative Arts Deaccession Fund and Cincinnati Art Museum Women’s Committee, 2017.62a–g. See this artwork in Gallery 228.

Designer and silversmith Emmy Roth created wares reflecting the realities of the modern interwar era in which she and her patrons lived. Her distilled forms were pure in line, spare in decoration, highly functional, and carefully handcrafted. For this service, Roth skillfully combined refined, rectilinear shapes with subtle scroll motifs, making it at once austere and organic, a striking and timeless combination.

Roth was one of the first critically acclaimed, published, and exhibited modernist female silversmiths to work in Germany. Unfortunately, her achievements were largely forgotten following her death, but recent scholarship has reinstated her well-deserved position in the canon of modern design and metalworking. Examples of Roth’s work are rare, and this is the largest service known to be created by the artist.

Shahzia Sikander (b. 1969)

Shahzia Sikander (Pakistani and American, b.1969), Caesura, 2021, painted and laminated glass, Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art, 2021.97a–k. See this artwork in Gallery 147–149.

Look up in Gallery 147, showcasing the museum’s ancient Nabataean collection, and you will notice a monumental artwork that occupies the clerestory windows across both sides of this gallery. Commissioned by the museum and inspired by the objects on view, this artwork creates dynamic connections between past and present. Shahzia Sikander is known for innovative works that engage playfully with scale, religion, culture, histories, and iconographies of power. While Sikander’s own identity connects with Pakistan rather than the countries of the modern Middle East, her practice mines cultural influences and forms that play across this vast region.

Sikander’s thoughtful response to the museum’s collection unites the ancient world with contemporary practices in visually imaginative and awe-inspiring ways. The title of this piece, Caesura, can be described as a pause in poetic form or a brief suspension that offers a chance to reflect. Here the artist brings this rhythmical pause to life in visual form. The lush depictions of the natural world and abstracted figural representation refract forms that have been explored in art from the ancient Middle East, through medieval Islamic cultures, and into the present. Incorporating a contemporary commission into these ancient galleries encourages multiple ways of seeing, reading, and understanding cultures—just as Sikander’s layered work suggests movement, color, density, gesture, and ever-shifting light.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Sikander’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on November 3, 2021.

Ayesha Singh (b. 1990)

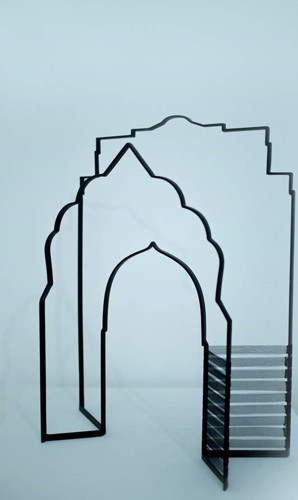

Ayesha Singh (Indian, b. 1990), Hybrid Prototype (edition 2 of 5), 2022, stainless steel with fabric detail, Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art, 2022.84. See this artwork in Gallery 143.

The British Empire in India carefully cultivated a hybrid transcultural identity recognizable within the architecture and decorative arts made from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. The aesthetic combined markers of South Asian kingdoms and British empires as a way to legitimize rule. Ayesha Singh’s Hybrid Prototype questions these sociopolitical histories by exploring the continuous coexistence of colonial architecture within modern India’s urban centers—spaces where histories of colonial oppression, Indian independence, and current political entities all intertwine.

Inspired by New Delhi’s India Gate, a war memorial, Hybrid Prototype blends motifs from Gothic, Victorian, Rajasthani, and Mughal architecture. Singh calls upon remembered experiences of space and emphasizes coexistence. The huqqa (waterpipe) base nearby was made for export to India. Its form and function reference British and Roman histories and motifs. Likely manufactured by Wedgwood, this was crafted to appeal to the colonial Englishman abroad who had adopted India’s elite customs yet still craved the aesthetics of home. And so, these two hybrid forms hold conflicted histories alongside nostalgic emblems of place and identity.

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (1875–1942)

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (American, 1875–1942), Barbara (Wallflower), 1915, bronze, Museum Purchase: Martha and Carl Lindner III Fund, 2017.61, © Estate of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney. See this artwork in Gallery 151.

This sculpture’s impressionistic surface heightens its feeling of spontaneity and informality. The intimate bronze statuette portrays Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney’s youngest daughter, Barbara Whitney (1903–1982). Barbara’s casual dress and spirited attitude, with her hands shoved into the pockets of her short trousers, mark her as a modern, active, and independent-minded adolescent. Barbara’s youthful enthusiasm for sports carried into her adulthood; she owned a horse racing syndicate in Lexington, Kentucky.

Whitney is the celebrated champion of vanguard American artists who founded the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. Her activities as a professional sculptor, however, are little known today. As a member of high society and a woman, Whitney fought for recognition as an artist and ultimately won public commissions that included the Women’s Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C., and a monument to Buffalo Bill for the state of Wyoming.

Listen to a museum staff member discuss Whitney’s work in this CAM Look episode posted on September 18, 2020.

Discover works by women artists in the museum’s open-access Photobook Collection

Browse these physically compact, conceptually expansive works of art at your leisure in the Mary R. Schiff Library. Women artists represented in the museum’s FotoFocus Photobook Collection include Gabriella Angotti-Jones, Sophie Calle, Nona Faustine, LaToya Ruby Frazier, Gauri Gill, Nan Goldin, Katy Grannan, Justine Kurland, Deana Lawson, Mary Ellen Mark, Susan Meiselas, Cristina de Middel, Nancy Rexroth, Alessandra Sanguinetti, Dayanita Singh, Carmen Winant, and many others. Browse the collection.

Explore more works by women artists in the museum’s collection with this self-guided tour through our galleries.