- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

A Peek into Museum Storage

by Emily Bauman

1/3/2017

curatorial , behind the scenes , collection storage , photograph , CAM

One of the wonderful things about the Art Museum is that the collection offers so many types of objects—there really is something for everyone. I am drawn to varied styles and media, but as a curatorial assistant in the museum’s department of photography, I am particularly devoted to photographs.

I spend my work days at the museum just a few minutes’ walk from the cultural treasures on view in the galleries. Of course, as in most museums, many objects in the collection are not currently on view. Photographs, like other light-sensitive media such as textiles or prints, require dark storage to slow fading. Even with the museum’s regulated gallery lighting, a photograph can only be exhibited a few months at a time in a span of a few years. This means that, for me, it is something really exciting when a photograph comes on view—it is an occasion, an opportunity for people to visit with something that, in order to preserve its long life, must remain in storage the majority of the time.

Our photographs are stored in archival boxes in a climate-controlled space. Recently, I had occasion to open the box that holds both Anna Atkins’s Myrrhis Odorata and Henry Fox Talbot’s The Scott Monument, Edinburgh, in the Course of Construction.

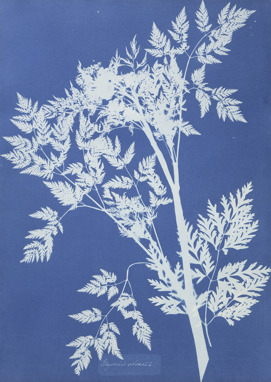

Image Credit: Anna Atkins (1799–1871), England, Myrrhis Odorata, ca. 1854, cyanotype, 3 7/16 x 9 1/2 in. (34.2 x 24.2 cm), The Albert P. Strietmann Collection, 1985.21.

Botanist Anna Atkins is not only credited as the first person to make a book illustrated with photographs, but also the first woman to make photographs. Her handmade book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions (1843) is a pioneering scientific reference work, a methodical study of plant and algae specimens illustrated with brilliant blue cyanotypes. Astronomer John Herschel had introduced the camera-less cyanotype process just a year earlier; Atkins made the plates by placing wet algae directly on light-sensitized paper and exposing the paper to sunlight. Myrrhis Odorata, part of a later study, shows the white imprint of a cicely plant. The plant’s delicate fronds against the unmistakable cyan tone are a breathtaking reminder of Atkins’s contributions to photography and science.

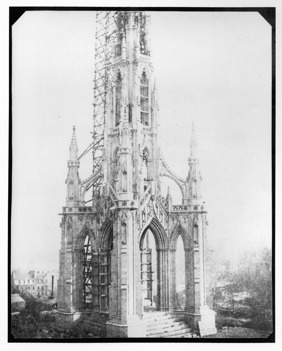

Just as Myrrhis Odorata stops me in my tracks, the soft, dreamy contours of William Henry Fox Talbot’s Scott Monument seem to demand a few moments of quiet contemplation. In the autumn of 1844, Talbot made a series of photographs for his book Sun Pictures in Scotland, which contained 23 salted-paper prints from calotype negatives. The Scott Monument was one of the included images.

Image credit: William Henry Fox Talbot (1800–1877), England, The Scott Monument, Edinburgh, in the Course of Construction, 1844, salted-paper print from paper negative, 7 3/4 x 6 1/4 in. (19.7 x 15.9 cm), The Albert P. Strietmann Collection, 1979.39.

Talbot is a key inventor on the path toward photography as we know it today. In the 1830s, Talbot had been dissatisfied with the camera lucida as a drawing tool, and resolved to find a better way to fix images on paper. He continued to experiment with light-sensitive chemicals, and by 1840, he was able to present his negative/positive calotype process to the public. (Talbot’s announcement came shortly after Daguerre revealed the metal-based daguerreotype process he developed with Nicéphore Niépce.) Incidentally, Talbot’s The Pencil of Nature, published in six installments from 1844 to 1846, is the first book with photographic illustrations to be commercially published.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: