Exploring Connections: Pak Sheung Chuen and Anila Quayyum Agha

by Dr. Ainsley M. Cameron, Curator of South Asian Art, Islamic Art and Antiquities

12/15/2017

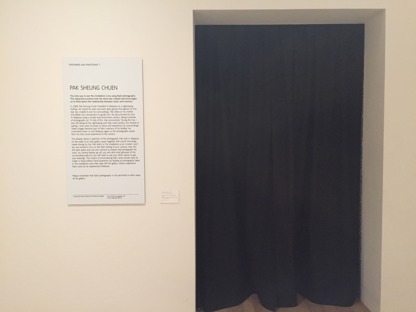

On a recent visit to London’s Tate Modern, I came across an installation of Pak Sheung Chuen’s A Travel without Visual Experience in a display of the museum’s permanent collection in the newly-opened and installed Blatvatnik Building. Continuing the Tate’s thematic organizational strategy, Pak’s piece was located in a series of galleries titled Performer and Participant.

Installed as a discrete and enclosed space within a larger gallery, there is one entrance into the interior room that reveals a pitch-black space. Instructions on the wall panel outside explain that the way to experience the artwork is by using flash photography. This counter-intuitive use of the visitor’s camera in a museum space echoes how the work was created and encourages us to consider the relationship between vision and memory (a dying skill in the age of the smartphone). Taking out my phone to experience the installation reminded me of the Cincinnati Art Museum’s recent exhibition of Anila Quayyum Agha’s All the Flowers Are for Me (Red) – quite possibly our most-photographed work of art.

Pak Sheung Chuen (Chinese, b. 1977), A Travel without Visual Experience, 2008, Wallpaper, photographs, digital print on paper, and sound recording, Presented by Richard Chang 2010, Tate Modern, T13694.

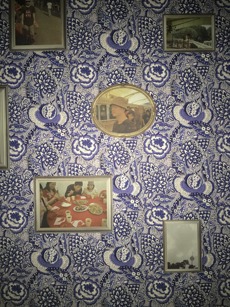

While in Malaysia on a sightseeing holiday in 2008, the China-born, Hong Kong-based artist closed his eyes and wore dark glasses for the duration of his five-day trip. Unable to see his surroundings, Pak relied on his mother and fellow companions to guide him physically and sensorially through the country’s markets, historic sites, landscapes, and streets. He documented his time by taking pictures with a simple point-and-shoot film camera. During the trip he took hundreds of photos, but since he was without sight for these five days, the photos are the only visual experience he encountered.

When you enter the room, you are immersed in darkness, cautiously holding your phone in front of your face and following the clearly laid-out instructions read outside: “You are invited to turn on the flash of your camera to explore and photograph the room. As camera flashes go off, you will catch glimpses of the surrounding walls but you will need to use your other senses to get your bearings.” When you take a photo in a darkened room, the flash illuminates space for a moment before the camera captures the image. In that moment, the flash reveals brightly-patterned walls covered in a selection of Pak’s photographs from the trip. As soon as the photo is taken, the darkness returns, and you are left with a trace of the experience on your phone. Pak’s photographs range from typical tourist shots of buildings and streets, but also include casual and unguarded images of Pak himself, along with his mother and other family friends. You are invited into a family holiday, participating in the experience by re-photographing holiday snapshots.

Pak Sheung Chuen (Chinese, b. 1977), A Travel without Visual Experience, 2008, Wallpaper, photographs, digital print on paper, and sound recording, Presented by Richard Chang 2010, Tate Modern, T13694.

Looking at the photographs you’ve captured clearly resonates with how Pak experienced his trip to Malaysia, and adds to this sense of intimacy as you now share a reminder of his trip on your phone. And the whole time you are doing this – illuminating space for brief seconds before taking a new photograph, you are aurally experiencing street sounds of Malaysia. The mosque’s call to prayer softly plays in the background, alongside the sound of cars and motorbikes, and people talking. Your sense of hearing is heightened without sight, as it likely was for Pak on his initial trip.

By including this work in a themed installation that explores Performer and Participant, the Tate is very consciously encouraging us to consider how this work is effectively placed to reference both. The act of a sighted person navigating the streets of Kuala Lumpur blindfolded is itself a performance, if not necessarily intended for a wider audience. And you, the visitor, become the active participant in his work through your experience.

I found the act of participating in the artwork’s delivery thrilling, and the experience compelling. This concept of actively engaging visitors in their experience of an artwork is something I’m fascinated by – how, as a curator, can I encourage intimate and personal connections between a work of art and our experience of it in a gallery setting?

Interesting parallels exist between Pak’s A Travel without Visual Experience and Anila Quayyum Agha’s All the Flowers Are for Me (Red), recently acquired and exhibited at the Cincinnati Art Museum.

Anila Quayyum Agha (Pakistan/United States, b. 1965), All the Flowers Are for Me (Red), (detail) laser-cut lacquered steel and halogen lightbulb, Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art, 2017.7.

Light emanates from the center of Agha’s a laser-cut steel cube, enveloping the gallery in intricate shadows. Her open and immersive installations reference Islamic architectural motifs, as well as the artist’s own experience living as a migrant in the United States. Agha addresses ideas of isolation and displacement by physically enveloping visitors in transmitted light, creating a sense of belonging through shared experience. Visitors respond by photographing the work – and themselves with it – constantly. It is a beautiful backdrop for a selfie, but it’s more than that. Museum visitors in the 21st century want to capture their experience, their memory, through their camera in order to share it with loved ones (and/or followers on Instagram). Speaking with our visitors and reading their responses to the piece, most people experienced a very visceral reaction to Agha’s work. They found the space calming and inviting, and they appreciated the connection to the artist’s personal narrative. (Agha created this work to explore ideas of detachment and disconnection that come from living as a migrant. Having just returned to the US after celebrating her son’s wedding in Lahore, she received word that her mother had died. The distance between her two homes seemed to give an intangible form to her grief, as if physical distance redoubled her loss.) Agha uses beauty and awe to erase boundaries, borders, and distance between those that physically share the gallery space.

L: Pak Sheung Chuen (Chinese, b. 1977), A Travel without Visual Experience, 2008, Wallpaper, photographs, digital print on paper, and sound recording, Presented by Richard Chang 2010, Tate Modern, T13694.

R: Anila Quayyum Agha (Pakistan/United States, b. 1965), All the Flowers Are for Me (Red), (detail) laser-cut lacquered steel and halogen lightbulb, Alice Bimel Endowment for Asian Art, 2017.7.

It is the creation of immersive space – and visitor participation in this experiential environment – that fundamentally connects the two works. Pak creates an enclosed space that is devoid of light. This intimate space is initially quite unnerving as it removes a primary sense from the sighted visitor, only to replace it, in fleeting moments, due to a camera’s flash. It is the visitor’s action of taking a picture that alters the space and reveals the images that cover all four walls. As a compelling counterpoint, Agha very consciously created an open and welcoming space. She floods a large gallery with light, manipulating space through her medium to extend the reach of her work. All the Flowers Are for Me (Red) is not confined to the cube hung in the center of the room, but includes the floral patterns cast on the walls, floor, and ceiling. The visitor’s physical presence becomes a part of the artwork, as the shadows ripple and change as you walk through the space. And the visitor’s experience of capturing the moment on their phone – of creating memory – exists well beyond the four walls of the gallery space, let alone the museum.