- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

How Many is Too Many?

by Nathaniel Stein

1/22/2018

curatorial , multiple mediums , photography , Contemporary Art , galleries , Curatorial Blog

Have you ever noticed that every gallery in the museum has a mood? In the Albert E. Heekin and Bertha E. Heekin Gallery (also known as Gallery 212), a dark wooden wainscot that runs all the way around the room is a big part of what sets the tone – distinguished, maybe even a bit formal. If you’ve never noticed the wainscot or you can’t see it in your mind’s eye as you read this, you’re forgiven. The museum’s exhibition designers and installation team work hard to make everything about a given space feel like a natural fit for the artwork on display there, so the atmosphere helps the art speak without sending out competing messages of its own.

Since the museum is made up of several buildings that have been added and joined together over the years, curators and designers work with a diverse palette of spaces. The Western and Southern Galleries (G232 and 233, where big special exhibitions go) are stripped down and built back up between each show so the environment is right. The Manuel D. and Rhoda Mayerson Gallery (G231, where contemporary art from the permanent collection is on display) has a light wood floor and tall walls that create the nearly featureless “white box” much contemporary art is made to live in. The Thomas R. Schiff Gallery (G234, currently featuring Albrecht Dürer: The Age of Reformation and Renaissance) has a geometric cut-out motif running around the soffit of its tray ceiling, and a beautiful herringbone parquet floor. In some exhibitions you’ll notice those details; in others, you won’t – depending on things like paint color and the position of temporary walls.

But back to G212. The wood paneling in G212 is lovely, but it also means the bottom 39 inches of the wall can’t be hung with art. In most cases curators work with a so-called 60-inch center, meaning framed works are hung so the vertical midpoint of the artwork lands at the 60-inch mark on the wall. To find out how much of an artwork falls below the 60-inch point on the wall, divide its height by 2. Solve for x in G212 and you’ll find it’s tough to hang anything taller than, say, 41 inches.

The museum has a great collection of contemporary photography and contemporary photographs tend to be very big. This brings us to one of those tricky pragmatic concerns curators navigate when planning an exhibition. Although much of our time is spent thinking about historical and cultural questions, we’re also working around the practical: literally, what fits?

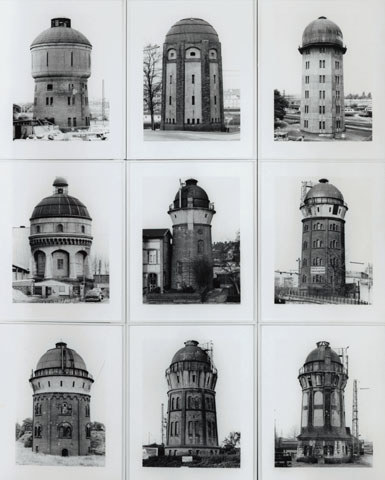

When the museum opens on Tuesday, there will be a new exhibition in G212, Multiple Medium: Photographs from the Collection. It will feature rarely seen treasures and new acquisitions that speak to photography’s many-faceted relationship with the multiple images. For students of photography, this subject leads directly to the German photographers Berndt and Hilla Becher. The Bechers gained fame for their typologies: cool, highly detailed photographs of examples of a given kind of industrial structure, presented in grids composed of many images.

Image Credit: Berndt and Hilla Becher (1931-2007 and 1934-2015), Germany, Water Towers, 1980, gelatin silver prints, 60 3/4 x 48 3/8 inches (154.3 x 122.9 cm) overall, Gift of RSM Co., 1985.326.1-9, © Hilla Becher

In fact, the Bechers are key figures in the history of contemporary photography. Their grids have been tremendously influential on other artists and are prized by collectors. The Cincinnati Art Museum’s collection boasts two of these photographic grids as well as a maquette, or model, for a third. Unfortunately, with two or more rows of pictures stacked on top of one another, the grids are too big for the exhibition gallery. So the curator (in this case, me) has to find other ways to put the Bechers and their important work on the visitor’s mind. For the close readers among us: the Bechers are mentioned in a label for a work that is in the exhibition, and there are photobooks for browsing in the gallery that gesture towards their influence. (Not to mention, of course, this blog entry!)

Every curator has a list of works she or he would love to put on view when circumstances – including the dimensions of walls and doorways – are right. The Becher grids are near the top of mine.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: