- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Digitally Engaging the Ancient Middle East

by Trudy Gaba, Curatorial Assistant of South Asian Art, Islamic Art, and Antiquities

7/27/2021

ancient Middle East , digital engagement , Persepolis , Middle East galleries , Khirbet et-Tannur

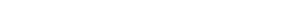

Figure 1: Screenshot of the main landing page of the interactive that situates diverse collection objects on a map to introduce the interconnected nature of this large geographic region.

This past month I co-wrote a short article in the upcoming Winter 2021-2022 Member’s Magazine with Julia Olson, Andrew W. Mellon Foundation Curatorial Research Fellow. In it, we previewed a digital interactive map (figure 1)—an exciting new interpretative tool that visitors will be able to experience when the ancient Middle East galleries return to view in the winter of 2021. The approach to this map is to encourage a deeper, more layered understanding of a carefully selected group of 32 ancient objects. This sneak-peek at what museum visitors can expect prompted me to continue this discussion here on the museum’s blog with a look at two additional objects. I want to share more on how this exploration into the permanent collection, through a model of digital engagement, has revealed exciting new ways of seeing and thinking about the art, architecture, and cultures of the ancient civilizations of the Middle East.

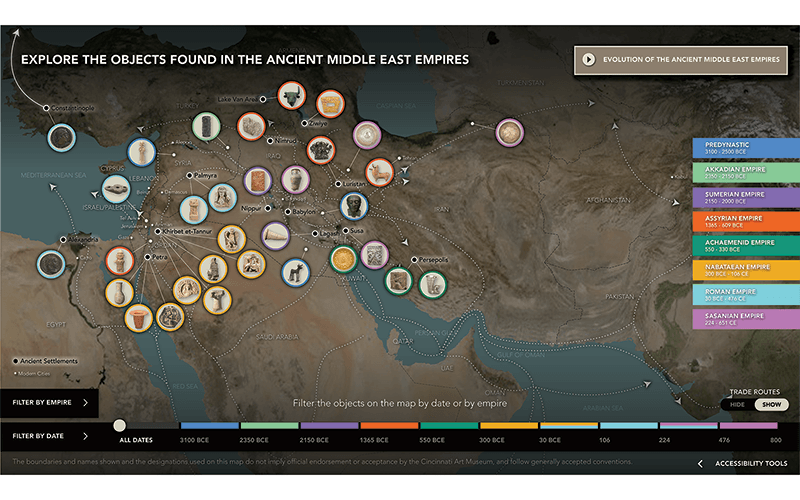

Figure 2: Fragment of a Stone Relief Depicting a Guard in Persepolitan Dress, 500–401 BCE, Persepolis, Iran, Achaemenid empire, limestone, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John J. Emery, 961.288 and photograph of the relief in situ at the Palace of Xerxes in 1878, Stolze Andreas vol I 1882 (published in Berlin).

The ancient site of Persepolis, located in south-central Iran, was a major center for economic and political affairs under the Achaemenid empire. It was also a beautifully decorated city with a formidable architectural program, first conceived of and constructed by Darius I (522–486 BCE), and expanded upon by his successor, Xerxes I (486–465 BCE). This fragmented relief, depicting a guard in Persepolitian dress, does little on its own to convey the monumentality of the art and architecture of Persepolis. With the aid of Dr. Lindsay Allen, Lecturer at Kings College, London, who recently brought this 1878 photo (figure 2) to the attention of our curatorial department, are we able to provide a visual link to our relief’s original location between the Council Hall and the Palace of Xerxes. With this aid, we can more effectively communicate in the gallery the scale and repetition of this relief, whose positioning was alongside hundreds of other carefully carved forms.

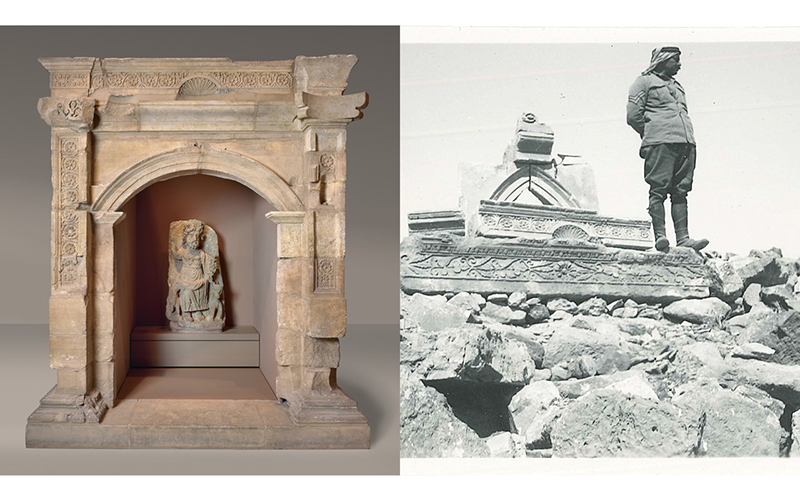

Figure 3: East Façade of Shrine, 101-200, Khirbet et-Tannur, Jordan, Nabataean Kingdom, limestone, Museum Purchase, 1939.22 and photo of Ali Abu Ghosh, a colleague of Nelson Glueck, surveys the temple ruins while standing upon the recently excavated architrave blocks and inner shrine of Khirbet et-Tannur. Photo courtesy of ASOR and Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, (September 10, 1936).

In December of 2019, I traveled alongside Ainsley Cameron, project lead and Curator of South Asian Art, Islamic Art, and Antiquities, to the Harvard Museum of the Ancient Near East, Boston, to research the archived materials from the 1937 excavation of Khirbet et-Tannur, a Nabataean temple complex. Khirber et-Tannur, located seventy kilometers (forty-five miles) north of Petra in Jordan, was excavated by the Department of Antiquities of Transjordan, working in conjunction with Dr. Nelson Glueck (1900–1971), an archaeologist and scholar of ancient Israel, Palestine, and Jordan from Cincinnati, then based in Jerusalem. Our research visit proved fruitful, returning to Cincinnati with a breadth of material that provides exciting new entry points into our collection of Nabataean sculpture, which has the largest holdings outside of Jordan. Digitizing Glueck’s extensive and well-documented catalogs of excavation photos from Khirbet et-Tannur as a feature on this platform is an integrative approach that helps to foster more meaningful connections to our collection. This juxtaposed image (figure 3) of the reconstructed inner shrine next to a photo of Ali Abu Ghosh, a colleague of Nelson Glueck’s, brings back into conversation the narratives and identities of community members local to the site, whose labor and expertise are often eclipsed from the historical record.

Tethering the disparate parts of these object narratives together through this digital in-gallery offering has facilitated more dynamic, nuanced, and inclusive ways of experiencing and perceiving a collection of art that spans over four thousand years and across a vast geographic region. If you would like to learn more about the arts and cultures of the ancient Middle East or experience the interactive map for yourself, you only have to wait a few more months. This winter, the museum will re-open its newly renovated and reinterpreted ancient Middle East galleries. I hope to see you there!

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: