- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Discovering Ansel Adams – SketchCAM

by Bruce Petrie, President, Board of Trustees

9/27/2024

Sketching , SketchCAM , Ansel Adams , Discovering Ansel Adams , photograph , landscapes

For this edition of SketchCAM, let’s take our sketchbook and pencil into Discovering Ansel Adams, featuring the landscape photography of Ansel Adams (1902–1984) on view from September 27, 2024 to January 19, 2025.

Adams’s perspective was of a lifelong environmentalist, awestruck by wilderness. He didn’t in a sense “take” pictures of landscapes but created what he called “visualizations” of a point of view. “There are two people in every photograph,” he said, “the photographer and the viewer.”

Adams created an emotional connection between nature, viewer, and photographer that was both public and intimate. This intimacy inspires a feeling of awe, a personal experience of reverence for the natural world that you have likely felt. The public part includes the photographer’s celebration of America’s national parklands and the belief that art has the power to move opinion to protect wilderness. This conviction has a proven track record historically; American landscape painters before Adams inspired the environmentalism of President Theodore Roosevelt and the American parks movement.

It’s one thing to feel awe before nature. It’s another to learn the tools and technical means to convey awe through artwork. Adams did this through keen attention to tonal values.

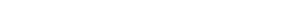

To explore tonal values, let’s go to our sketchbook. We’ll draw a simple value scale and then a quick 10-minute value study sketch of Adams’s photograph The Tetons and Snake the River, Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming (1942).

Take a ruler, measure out five inches, draw five squares in a row and number them one through five. Leave square #1 white. Fill in square #5 in black. Then shade in squares #2, #3, and #4 in gradations from light to dark. With this value scale in mind, sketch the landscape and observe where Adams captures the darkest darks, the lightest lights, and the shades of gray in between.

Tonal values are fundamental to painting as well. A quick story: The first outdoor painting classes I took were in the 1980s in the Finger Lakes Region of Upstate New York with a wonderful instructor named Tom Buechner. We set up our easels all day on summer hillsides with panoramic views of vineyards, lakes, purple horizons, and big dome skies. Being awestruck was the easy part. The hard part—nature doesn’t stand still! Sunlight, shadows, clouds, trees, and wind are all in motion. Tom’s advice to the rescue: “First establish your values.”

We set down our brushes and took 10 minutes to do a value sketch of the scene in pencil in our sketchbooks. Then with brush on canvas, using only one color, we blocked in the scene’s big basic shapes, establishing darks and lights (also known as an ’underpainting imprimatura’). Only after we had the big values set did we add details and colors on top.

Nature inspires but leaves the creative process to each of us. As Adams said: “You don’t take a photograph, you make it.” Finally, he said: “Life is your art. An open, aware heart is your camera…Your bright eyes and easy smile is your museum.”

So, we hope to see you at CAM.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: