- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

John C. Lutz Rediscovered

by Julie Aronson, PhD, Curator of American Paintings, Sculpture and Drawings

8/7/2024

John C. Lutz , Curatorial Blog , Works Progress Administration , WPA , Great Depression , Black Sunday

The Cincinnati Art Museum recently acquired the painting Black Sunday of 1937 by John C. Lutz, the only Black artist in Cincinnati (and one of four in Ohio) hired on the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), the government program that provided employment during the Great Depression. The acquisition is noteworthy as few locations of Lutz’s works are known. The reconstruction of his artistic journey is itself a work in progress. Here’s what we’ve discovered so far:

John Choram Lutz was born on July 27, 1908, in Hickory, North Carolina, and was one of 11 or 12 children of Fanny Whitener (1887–1935) and John Thomas Lutz (1884–1940), a barber and musician with a late career as a vaudeville and radio performer. John Jr.’s talents for drawing on the blackboard attracted notice at the grammar school he attended in Hickory. According to census records, he completed the second year of high school. In 1925, the young man moved to Ashville, North Carolina, and by 1930 to Atlantic City, New Jersey, where he may have found employment as a hotel porter and studied at a trade school for a year. Lutz’s next move was to Cincinnati. Records of the Art Academy of Cincinnati note his enrollment in free evening classes from the fall of 1934 to 1936 under the painter Herman H. Wessel (1878–1979). He also took advantage of the lithography class of Maybelle Stamper (1907–1995) in 1937.

Lutz registered with the WPA in 1935. Although “artist” was his preference, he worked in construction until officials who recognized his talent transferred him to the art division. Under the auspices of the Ohio branch of the Federal Art Project, he made easel paintings, drawings, and murals. According to a feature story in the Cincinnati Enquirer of June 22, 1936, the artist Paul Craft (1904–1981), the District Supervisor for Cincinnati, thought highly of Lutz’s prospects:

“John is a very sincere artist … He has talent; and even more than that, he loves to draw and paint. The Federal Art project has given him an opportunity to display that talent and he is responding with unusual and original pictures.”

The article’s degrading headline, “Young Negro Artist Wins Praise for Work on Federal Project; Can Dig Ditches, Too,” lays bare the racist attitudes Lutz endured. Yet, the article’s content suggests the young artist’s ambition and nascent reputation.

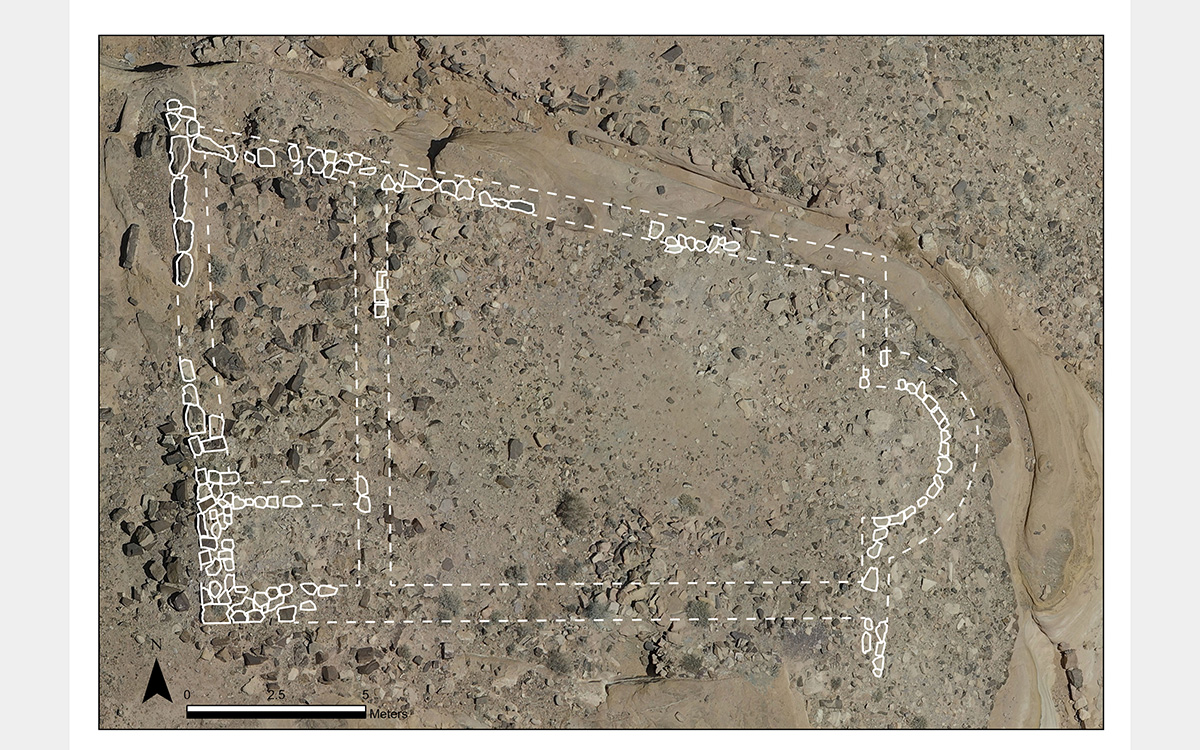

Lutz’s most important contribution to the project, The Development of the Negro Race, for Cincinnati’s Harriet Beecher Stowe School, a school for the education of black children, was unveiled in 1937 but is no longer extant. A portrait of the school’s founder and principal, Jennie Davis Porter (1876–1936), the first Black woman to earn a PhD from the University of Cincinnati, appeared in Lutz’s composition. He also produced studies for a mural for the recreation room of the Administration Building of the Metropolitan Housing Authority in Columbus and for the Garfield Public School in Cincinnati, but whether he completed these commissions requires further archival research.

Lutz’s work, Black Sunday—recently gifted to the museum—is named for January 26, 1937, the apocalyptic day when the surging Ohio River submerged nearly one-fifth of Cincinnati underwater.

This Depression-era flood was among the most devastating events in the city’s history, leaving thousands of people already suffering economic hardship injured, dispirited, and homeless. Artists like Lutz and his teacher Herman Wessel responded with compassion, making works of art that drew attention to the victims’ plight. Lutz handled his painting much like an oil sketch, using ruddy browns and heavy, expressive outlines to convey the dire emotional and physical consequences of this natural disaster. His “very poignant and sympathetic painting” (quoted from a government report) caught public notice at an exhibition Craft organized at Cincinnati’s Mayfield Theater before heading to the School of Social Administration at the Ohio State University.

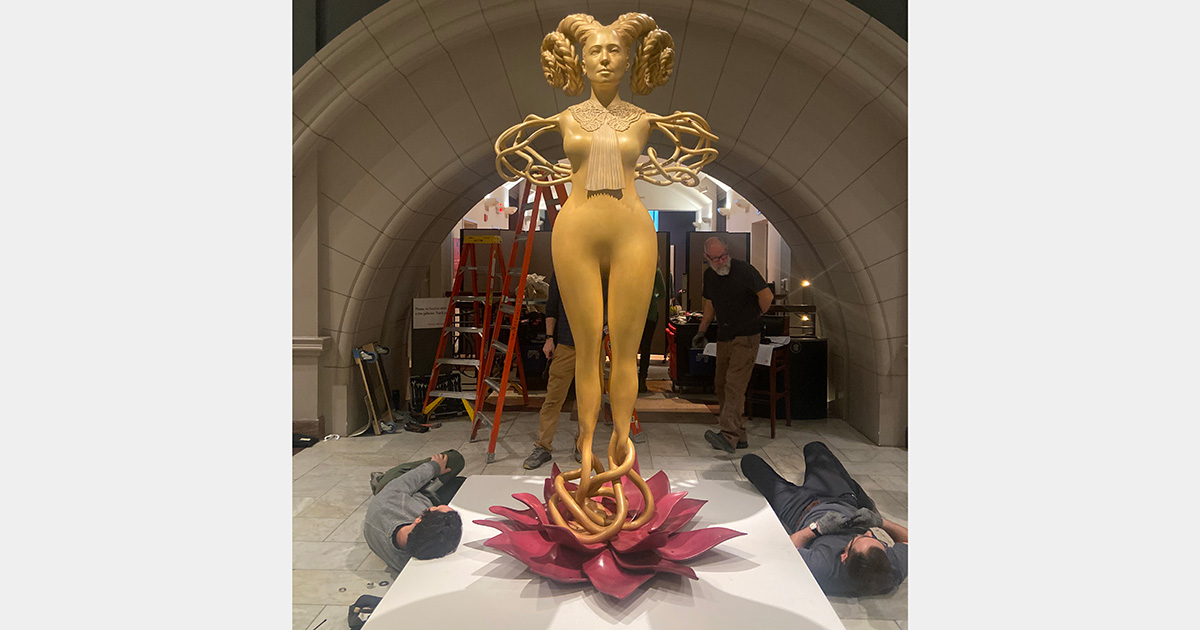

In the 1930s and early 40s, Lutz propelled his art career forward while he did what he could to validate and support people of color. At the Cincinnati Art Museum and commercial galleries, he exhibited paintings and drawings depicting the lives of Black people, as well as figures and heads carved in wood or stone. Shows dedicated to promoting African American art included his work, notably the American Negro Exposition of 1940 held in Chicago. In 1939, Lutz established a studio in an old bath house at 815 Mound Street in Cincinnati and formed a small, probably short-lived group called Creative Negro Artists for whom he is said to have provided critiques.

After 1942, Lutz’s professional activity appears to have dwindled; one suspects that with the end of the federal art program he could no longer make ends meet as an artist. Family life may have also interceded. In 1946, he divorced his wife, Emma Lee Lutz (b. 1917), a domestic worker from Kentucky, after her service in the United States Army. Although he appears in the Cincinnati city directory in 1947, by 1948 he had returned home to Hickory, where he married a widow named Occie Settles (1922–1996) with whom he had children. In the 1950 census, Lutz is listed as a building contractor in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He died on June 28, 1988, in Minneapolis and is buried there in Lakewood Cemetery.

Look for Black Sunday in Gallery 122 of the museum’s Cincinnati Wing beginning in mid-September. If you have further information on John C. Lutz or know the whereabouts of his artwork, the Cincinnati Art Museum would love to hear from you.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: