Mary R. Schiff Library and Archives August Display: The Case of the Purloined Painting

by Geoff Edwards

8/18/2017

THE CASE OF THE PURLOINED PAINTING

A century old theft, a misappropriated masterpiece, and the rogue responsible

If you visit the Mary R. Schiff Library during August, you’ll see a display of materials relating to the theft of a painting from the museum in 1906. The story of the theft, however, is secondary to the story of the thief himself. A slippery scoundrel with numerous aliases, Clarendon Henri was apparently an accomplished thief, only let down by his inability to not get caught…

Sometime during the morning of Monday, October 17th, 1906, a painting was stolen from the Cincinnati Art Museum. The work in question, a small nineteenth century oil titled “Young Girl Knitting” by German artist Meyer von Bremen, was cut from its frame and spirited away.

Without CCTV, alarms or other modern security measures, the theft wasn’t immediately discovered, and by time the alarm was finally raised, the thief was long gone. Although there were no witnesses to the crime itself, the museum’s sculpture curator, Clement Barnhorn, and a gallery attendant, William Flinchpaugh, had both noticed a man who had struck them as a potential suspect. Barnhorn provided police with the following description: “A young man, about 5 feet 5 or 6 inches tall, rather slim, brown hair, smooth face, and wearing a flat brim derby hat and a long gray cut-away coat”. Flinchpaugh thought him a little taller, maybe 5’ 8”, and guessed he might be German, based on his accent. He had seen him at the museum on both October 16th and 17th, and at the time thought he was a “nice, genteel looking fellow”.

Police were not initially optimistic that the painting or the thief would be located. However, they got a break in the case a mere five days later. On Friday, October 22nd, a man claiming to be a dealer in antiques and paintings from London entered Schaus Art Galleries at 415 Fifth Avenue, New York; he gave his name as Clarendon Henri. Newspaper reports would describe him as, “typically English in appearance…His suit was of tweed, and he wore pearl gray spats and an aggressively correct derby hat”.

From a package, the supposed dealer produced two pictures. The first was a minor work of no interest to the gallery owner, Mr. Schaus, but he immediately recognized the second as “Young Girl Knitting”, having seen reports of its recent theft. Henri claimed to have bought the picture at Christie’s auction house in London, and was asking $275 for it ($7500 at today’s prices). Thinking quickly, Schaus asked if Henri would leave the painting with him over the weekend, to give him time to decide whether he wanted to purchase it. Somewhat surprisingly, Henri agreed.

As soon as the suspected thief left the gallery, Mr. Schaus called the police. He also contacted the Cincinnati Art Museum to inform them he had been offered the painting.

On Monday morning, a detective, William P. Judge, was sent to Mr. Schaus’ gallery. When Henri arrived, he was told the detective was an art connoisseur who wanted more information on the picture. In the conversation that followed, Henri changed his previous story and claimed to have acquired the painting in Berlin rather than London. Convinced of his guilt, Detective Judge arrested Henri.

Held without bail, Henri protested his innocence, claiming he wasn’t even in Cincinnati when the painting was stolen. However, investigations would soon reveal that Henri was no innocent art dealer. He had a host of aliases, including Walter Wilson, Joel Smith, Arthur Eastman, R.T. Brown, Hargrave, and Bosworth. He had previously been arrested in New York for pick-pocketing, and had spent 18 months in a Canadian prison for forging a check for $167. He was also wanted in both Chicago and St. Louis in relation to the theft of artworks, but because the case against him was strongest for the Cincinnati theft, it was decided he should be sent there to stand trial.

Over the next few days there was a flurry of correspondence between New York and Cincinnati attempting to confirm the identity of the recovered painting and to confirm that Henri was indeed the man Barnhorn and Flinchpaugh had seen at the museum. An eyewitness identification placing the suspect in Ohio was essential if he was to be extradited under New York state law. To this end, both men travelled to New York; Barnhorn found he could not confidently identify the suspect, but Flinchpaugh was certain. A newspaper report describes how he was escorted to the prison where “he faced 10 prisoners lined up in the corridor. Making close examination of the men, Mr. Flinchpaugh finally paused before Henri and said: ‘There is the man’”. I like to imagine he also pointed dramatically.

To leave absolutely no room for doubt, a third witness to Henri’s presence in the Ohio was also located. Whilst in Cincinnati, it turned out that Henri had been posing as a scenic artist named Arthur Eastman, and had been lurking around the Harrison Building at Seventh and Walnut streets, where a number of local artists and art organizations had rooms. Police suspected he was simply looking for an opportunity to steal a painting, but instead he met Miss June Wilson, a professional art model from Covington, who must have caught his eye. Claiming to have a commission to paint a curtain for a local theater, he asked her if she would model for him for $12 per week. Wisely, Wilson was not convinced by his flimflam, and refused the offer. Along with Barnhorn and Flinchpaugh, she would travel to New York to identify Henri.

As a result of the witnesses’ testimony, Henri’s extradition was granted. He and the painting were returned to Cincinnati on November 6th. New York attorney James D. Fessenden, retained by the museum to help with the extradition process, wrote a note to museum director Joseph Henry Gest: “I congratulate you on having both [Henri and the painting] in a safe place, with so little difficulty. I trust the little scamp will be convicted, and gets a good long sentence”. The little scamp, however, had other ideas…

Back at the museum, “Young Girl Knitting” was placed in a new frame. Though slightly reduced in size, the main part of the painting had not been damaged, and its artistic value was not felt to have been lessened to any great degree. On its return, Director Gest said, “I’m highly pleased that the picture has been found. Its recovery, however, is not a surprise…Paintings by prominent artists are so well catalogued, and are so well known, that the thief is almost instantly detected when he offers one for sale. A picture, especially one in a public museum, is the last thing I would think a thief, for his own good, would want to steal”.

This is the end of the painting’s story, as far as we’re concerned. It was eventually deaccessioned from the museum’s collection in the 1940s, and its current location is unknown. However, Clarendon Henri’s tale is far from over.

Having been returned to Cincinnati, Henri was awaiting trial in the Hamilton County jail. But deciding that he didn’t want to spend Christmas in a cell, on the morning of Sunday, December 23rd, he and eight other prisoners escaped.

As reported in the press, the jailer was about to sit down for his Sunday lunch when a passing boy alerted him that he’d just seen nine men jumping off the jail roof. Suddenly losing his appetite, the jailer rushed to confirm the boy’s story and raised the alarm. It was discovered that the nine escapees included three burglars, a forger, a pickpocket, a highway robber, a horse thief, a murderer, and, of course, an art thief. Most of the men were quickly recaptured, but Henri remained on the lam. According to the failed escapees, it was Henri who had masterminded the jail break.

For the next few weeks nothing was heard of Clarendon Henri. Then, on January 8th, 1907, a man was arrested in Washington, D.C. for the theft of coins and gems from the Smithsonian. Though he initially gave the name of Edwin Letchmere, he soon admitted that he was, in fact, Clarendon Henri. However, he denied any involvement in the Smithsonian robbery, or in another theft of valuable stamps from the Post Office Museum. He did however, tell a reporter what he’d been up to since the prison break. On escaping, he immediately abandoned his fellow escapees and made his way to a little town in Ohio, disguised as a farmer. Here he found a room at a cheap hotel, having been mailed some money by a “contact” in New York. Over the next few days he kept a low profile whilst following the progress of the manhunt in the newspapers. He eventually decided to go to Washington, and then on to New York where he would flee to England. Having arrived in D.C., he was taking an innocent stroll in the grounds of the Capitol when, according to Henri’s version of events, a police officer mistook him for a completely different art thief - who had coincidentally just robbed the Smithsonian - and arrested him.

On learning of Henri’s recapture, Governor Harris of Ohio requested that Henri be returned to stand trial in Cincinnati. This request that was accepted, and arrangements were made to hand Henri over to Ohio authorities on January 19th. However, Henri almost slipped through their fingers once again. On the night of January 18th, a guard making his rounds noticed one of the bars of Henri’s cell had been sawed through. Henri admitted to the escape attempt; he had used an old razor blade (passed to him by an outside accomplice) and a piece of steel from inside his shoe to create a make-shift saw. He revealed that he had actually succeeded in getting out of his cell through the cut bar, but failed to make his getaway because his accomplice didn’t saw through the outer bars of the prison as planned.

As Henri left for Cincinnati on January 20th, he told a newspaper reporter: “I’m likely to stand trial for the Cincinnati job, and they won’t give me less than five years in the pen. But just watch me. I’m going to beat these fellows yet. I’m not going to a penitentiary if I can help it”.

Despite his conviction that he’d escape conviction, one way or another, he was in fact sentenced to four years in the Ohio state penitentiary on January 22nd, 1907.

Shortly after he began his sentence, he started to open up about his background and the circumstances of the Cincinnati theft. He reportedly told another prisoner how he used a small cane with a knife in the handle to cut the picture from its frame. He then placed the canvas in an inside vest pocket and left. Why did he do it? He would tell a reporter that he was broke and needed the money. Henri claimed that he had been born into a relatively well-off family. His father, John C. Henry (rather than Henri), who was from London originally, made a fortune as an inventor in the “electrical business”. However, in declining health, he decided to move to Colorado. Here, he obviously recovered somewhat as he was later instrumental in setting up a company manufacturing electrical heating and lighting equipment for railroad cars.

Henri claimed to have followed in his father’s footsteps and trained as a mechanical and electrical engineer. But when his father died, in about 1901, leaving him $45,000 (over $1,200,000 today), he began living the high life. Having quickly squandered his inheritance on fancy clothing and extravagant spending, he drifted penniless for a while, eventually washing up in Cincinnati. Looking for some easy money, Henri decide to pay a visit to the museum. His father had been something of an art connoisseur, so when the scoundrel came to the museum and saw “Young Girl Knitting”, he recognized the quality of the painting and made his move.

How much of this backstory is actually true? When you’re dealing with someone so slippery and with so many aliases, it’s hard to separate fact from fiction, but certain details do check out. For example, a John C. Henry with connections to an electrical equipment company did indeed exist, though he seems to have been Canadian, not English. He did live in Colorado and died in about 1901. With a little digging, you can actually find his will on Ancestry.com. Interestingly, he left his assets to his wife, his daughter, and a son named David Carl Henry – could this be Clarendon Henri’s true identity? Personally, I think so, but proving it is tricky.

So, what happened next? Henri (as we’ll continue to call him for clarity’s sake) apparently served his time in the Ohio State penitentiary without incident and was released on November 11th, 1909, just over a year early. After savoring literally moments of freedom, he was rearrested at the penitentiary gates to be taken to Washington to be tried for the Smithsonian theft.

Newspaper reports relate how, on arrival at the jail in Washington where he would await trial, the warden, who must have been aware of Henri’s previous form, ordered him strip-searched. His caution paid off; a small master key was found hidden on Henri, which could have opened any door in the jail. As a result, Henri remained safely locked up until his trial, where he was convicted and sentenced to a year and a day in the Atlanta penitentiary.

After this, Henri’s trail goes cold. The only other hint of what became of him is a World War I draft record in the name of David Carl Henry (Henri’s possible real name) who, in 1917, was living in New Jersey and working as a patent engineer. It’s nice to think that, perhaps, Henri eventually turned his life around and went back to being David Carl Henry.

Though his multiple aliases and murky background make him a tricky little scamp to trace, I’m still looking, and should any further information surface, I’ll be sure to provide an update.

All illustrations are from the Cincinnati Art Museum archives, except:

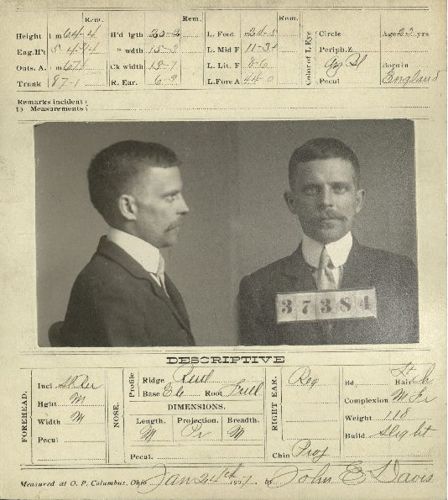

- Penitentiary Record Card, courtesy of Ohio History Connection (State Archives Series 1002 AV, Ohio Penitentiary Bertillon cards, 1888-1919).

- Image of “Young Girl Knitting” retrieved from Pinterest (https://www.pinterest.com/pin/137641332334216354/), originally pinned from world-market-portraits.blogspot.com (website no longer exists)