- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

The Dress of Tomorrow

by Cynthia Amnéus, Chief Curator and Curator of Fashion Arts and Textiles

10/6/2022

Cynthia Amnéus , The Saturday Evening Post , Triennale di Milano , Milan Trienniale , Evelyn Jablow , Fold-Up Dress for a Portable Society , 1964 , Fashion , Magazine , Curatorial Blog

“The woman of tomorrow will wear pleats and tights, and live in a house spun from glass fiber, with patent-leather walls and no furniture at all.”

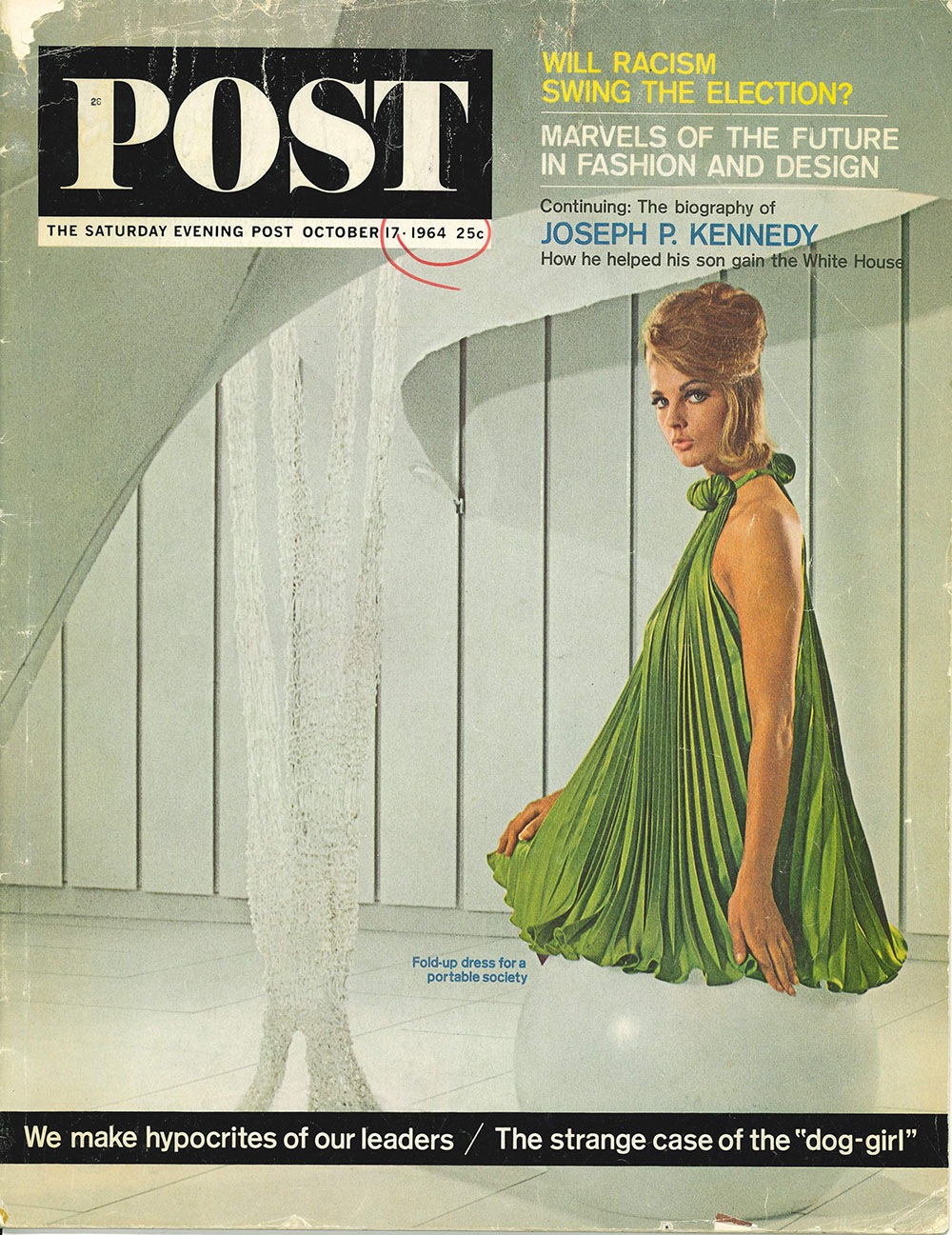

This quote is from the October 1964 edition of The Saturday Evening Post. This issue is all about the “marvels” of the future in fashion and design shown at the Triennale di Milano (Milan Trienniale) in the same year. The Cincinnati Art Museum has in its permanent collection the dress that was featured on the cover of the magazine.

The Saturday Evening Post, October 17, 1964, cover

Initiated in 1923 and continuing still today, the Triennale di Milano itself about leisure and its relationship to time spent working. However, the focus of many of the displays was the architecture of the future and the designers emphasized that this work would be based on the introduction of technological advancement. New materials used for rockets, space stations, and lunar vehicles were expected to be adapted to build houses for the first colonies in space. Rooms of the future configured in the exhibition halls included nylon stretch fabric that formed sculptural spaces that could be changed by the owner; plastic laminate floors; blow-up recreation halls; speaker systems that transmitted sound underwater for those with pools; and rooms with only platforms that took the place of furniture. If furniture was included, many thought it would be unadorned and shaped to the human body. Lighting would be woven into the walls, eliminating conventional fixtures and creating a soft glow.

Into this space, walked the twenty-first century woman. Everything in her life—her home, her clothes, her furnishings—would be created by the same designer who would be sufficiently trained to shape a dress as well as a house. Evelyn Jablow (1919–1997), who created this garment and others photographed for the publication, was a designer of interiors and furniture who was fascinated by the concept of creating a set of clothes for the woman of the future. Her ideas centered around the idea that the entire wardrobe would be contained in a cylinder no larger than a golf bag, which was compartmentalized to hold three or four pieces of clothing. These garments would be simple in design, made of lightweight fabrics, quite colorful, and could be worn in multiple combinations with ease of movement as their primary focus.

All Jablow’s designs were pleated and designed with a free form to fit any body shape. Prepackaged in a tube, they were a consistent size—36 inches long—so they could fit into a “travel pack” without folding. They would be worn with colored or patterned tights since the length of the garment exposed the legs significantly. Boots would be worn outside and soft slipper-like shoes indoors.

Evelyn Jablow (1919–1997), Fold-Up Dress for a Portable Society, 1964, silk, Museum Purchase, 2006.15

Our piece is the characteristic 36 inches long, pleated, and woven of a changeable silk in which were each a different color. Here they are gold and green, resulting in an overall green textile that shimmers and subtly changes color when worn. Called the Fold-Up Dress for a Portable Society, the garment’s design and its title point to the fact that the community of the future was one that could easily pick up and move at a moment’s notice.

This garment is currently on view at the Jewish Museum in New York City whose exhibition New York: 1962–1964 is open until January 8, 2023. Purchased by the museum in 2006 with little information about the designer, I am thankful that Joanne Jablow, Evelyn’s daughter, saw the dress in the Jewish Museum exhibition. She was able to get in touch with me and added much information to our knowledge about her mother. Evelyn Jablow, a native of Philadelphia, had a degree in liberal arts from New York University and was an accomplished interior designer who opened her own firm in the early 1950s. She later became a consultant to such corporations as the Wool Bureau and Monsanto, creating spaces for them at trade shows, for instance. She continued to design select pieces of fashion, never creating more than a few of any design. She was always happiest moving on to new ideas.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: