- Art

- Exhibitions

- Longing: Painting from the Pahari Kingdoms of the Northwest Himalayas

- What, Me Worry? The Art and Humor of MAD Magazine

- Special Features

- Upcoming Exhibitions

- Past Exhibitions

- Online Exhibitions

- Explore the Collection

- Provenance and Cultural Property

- Conservation

- Meet the Curators

- Digital Resources

- Art Bridges Cohort Program

Introduction - The Culture Audio Exhibition

Hi, I’m Jason Rawls, guest curator of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. I will be sharing the Introduction to the exhibition.

From the street to the runway, the artist's studio to the museum gallery, and countless sites in between, The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century explores hip hop's profound impact on contemporary art and culture. One of the most vital movements of the twentieth century, hip hop is now a global industry and way of life. In the twenty-first century, hip hop practitioners have harnessed digital technologies to gain unparalleled economic, social, and cultural capital.

Hip hop emerged in the 1970s in the Bronx as a form of celebration expressed by Black and Latinx youth through emceeing (rapping), deejaying, graffiti-writing, and breakdancing. Over the past 50 years, these creative practices have produced new forms of power as they critique, celebrate, and refuse dominant ones.

Hip hop has deeply informed ''The Culture," an expression of Black diasporic culture that has largely defined itself against white dominance. In the art museum, however, ''culture'' has historically meant a Europe-focused set of aesthetics, values, and traditions sustained through gatekeeping.

The works in these galleries explore where ''culture'' and ''The Culture'' collide through six themes: Language, Brand, Adornment, Tribute, Pose, and Ascension. Language, whether in words, music, or graffiti, explores hip hop's strategies of subversion. Brand highlights the icons born from hip hop and the seduction of success. Adornment exuberantly challenges white ideas of taste with alternate notions of beauty, while Tribute testifies to hip hop's development of a visual canon. Pose celebrates how hip hop speaks through the body and its gestures. Ascension explores mortality, spirituality, and the transcendent. Endlessly inventive and multi-faceted, hip hop, and the art it inspires, will continue to dazzle and empower.

A Great Day in Hip Hop Artwork

Gordon Parks (American, b. 1922 Fort Scott, KS, d. 2006, New York City), A Great Day in Hip Hop, 1998, photograph, Courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation, Pleasantville, NY

A Great Day in Hip Hop Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Jason Rawls, guest curator of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. I am sharing a description of A Great Day in Hip Hop by Gordon Parks in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Gordon Parks, an American photographer—whose life dates from 1922 to 2006—created this photograph, A Great Day in Hip Hop, in 1998. It is in this exhibition courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York.

In the large black and white photograph, A Great Day in Hip Hop, the artist, Gordon Parks, captures a posed scene of 177 people. The group poses in front of five brick brownstone buildings. The ensemble stands on the stoops of three and on the sidewalk in front of the buildings, creating a “W” shape. Most of the people pictured are Black, wearing a similar casual dress of jeans, sweatshirts, track pants, jackets, and a few don hats. Graffitied boards cover the brownstone door in the center and the window to its right.

A Great Day in Hip Hop Label

Hi, I’m Jason Rawls, guest curator of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century. I am sharing the label for A Great Day in Hip Hop by Gordon Parks in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Gordon Parks, an American photographer—whose life dates from 1922 to 2006—created this photograph, A Great Day in Hip Hop, in 1998. It is in this exhibition courtesy of The Gordon Parks Foundation in Pleasantville, New York.

In 1998, 177 people gathered on the steps of a brownstone in Harlem, New York, to celebrate the impact and evolution of hip hop. This photograph documents its exponential growth and unprecedented movement into mainstream culture.

Commissioned by the music publication XXL, A Great Day in Hip Hop is an homage to Art Kane’s (1925–1995) 1958 photograph, A Great Day in Harlem, which commemorates legendary jazz figures. By referencing Kane’s popular image, Parks’ work invites you to consider the evolution of Black sound from jazz to hip hop.

Language Section Introduction

Hi, I’m Cynthia Amneus, the museum’s chief curator and curator of fashion arts and textiles. I am introducing the Language section of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Hip hop is intrinsically an art form about language: the visual language of graffiti, a musical language that includes scratching and sampling, and, of course, the written and spoken word. An emcee calls to the crowd with, “Let me hear you say...” and orders language to a rhythm. Call-and-response chants, followed by rap rhymes and lyrics overlaid on tracks, form the foundations of hip hop music. In addition to the poetry of music, one of the most recognizable markers of hip hop is graffiti. Since the 1970s, graffiti writers have colored city trains, overpasses, and walls with vibrant hues of spray paint. Many writers sign their works with recognizable “tags.” Their exploration takes the recognizable shapes of letters and numbers and pushes their forms to—and beyond—the limit of legibility.

Hip hop artists convey messages for anyone to understand, while they code others in references, technologies, or forms that require insider knowledge, asserting the right not to be universally understood.

How do you read the language of hip hop in these works?

Brand Section Introduction

Hi, I’m Will Kendrick, a gallery attendant at the museum. I am introducing the Brand section of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

“I’m not a businessman, I’m a business, man!” exclaimed Jay-Z in 2005. Soon after, he became the first rapper to cross the billion-dollar net worth threshold. The concept of a brand is not limited to differentiating and marketing commercial goods but extends to how an individual uses available communication technologies—including social media—to position themself in the public sphere.

In previous decades, hip hop artists have functioned as unofficial promoters of major brands that aligned with their style and desired public persona. Today, artists both partner directly with companies and create their own independent brands to bolster their personal business empires. Whether designing fashion, recording music, or making art, artists blur the boundaries between these art forms, between being in business and being the business.

Is the artist a producer or is the artist a product?

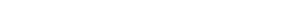

Cardi B Unity Artwork

Hassan Hajjaj (Moroccan, b. 1961, Larache, Morocco), Cardi B Unity, 2017/1438 (Gregorian/Hijri), From the series My Rockstars, Lambda metallic print on aluminum sheet, wood, and plastic green tea boxes, Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Cardi B Unity Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Will Kendrick, a gallery attendant at the museum. I am sharing a description of Cardi B Unity by Hassan Hajjaj in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Hassan Hajjaj is a Moroccan artist born in 1961 in Larache, Morocco. He created the work Cardi B Unity in 2017 on the Gregorian calendar or 1438 on the Hijri calendar. It is from the series My Rockstars. The work is a Lambda metallic print on aluminum sheet, wood, and plastic green tea boxes. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the Yossi Milo Gallery in New York City.

Cardi B Unity is a large vertically oriented color photograph measuring 55 and seven-eighths by 40 by four inches or 141.9 by 101.6 by 10.2 centimeters. In this image, the artist, Hassan Hajjaj, portrays the musician, Cardi B, sitting on a stack of two bright green plastic milk bins. Her body is in profile, turned to the right, while she turns her head to face the camera. She wears a black straight shoulder-length bob hairstyle and a gold hoop earring with two yellow rod-like attachments on her left peaks out. Her attire consists of a yellow, white, and black plaid dress with transparent black sleeves, the word UNITY written in white letters down the right arm, and a royal blue floral slip peeking out on her knees. Her shoes are black high-heeled sandals with floral decoration. She holds her hands in front of her, almost touching her lap.

Behind and under the feet of the performer, a red woven rug with white stars serves as the background and base of the photograph. What appears to be a three-dimensional white shelving unit surrounds the image. A round plastic tea box with a lid is on each shelf. Each container is green, pink, and white with a yellow butterfly and the words “Marque Deposee” written on the front. There are 38 boxes in all.

It was all a dream Artwork

Zéh Palito (Brazilian, b. 1991, Itaqui, Brazil), It was all a dream, 2022, acrylic on canvas, Courtesy of the artist, Simões de Assis and Luce Gallery, © Zéh Palito

It was all a dream Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Will Kendrick, a gallery attendant at the museum. I am sharing a description of It was all a dream by Zéh Palito in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Zéh Palito is a Brazilian artist born in 1991 in Itaqui, Brazil. He created the acrylic on canvas painting, It was all a dream in 2022. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the artist and the Simões de Assis and Luce Gallery. Zéh Palito owns the copyright.

It was all a dream is a square painting measuring 68 by 68 inches or 172.7 by 172.7 centimeters. Here, the artist, Zéh Palito, paints a colorful scene of two people in front of two hot-rod-style automobiles. The Black woman in the left foreground appears in her early 20s. She is wearing her hair in shoulder-length, white dreadlocks that frame her face, an oversized gold hoop earring in her left ear, and three gold chains around her neck. Her clothing consists of an unzipped light pink jacket with the words “Fubu” and a crab on the front and darker pink pants. She holds her hands, donned with two gold rings, in front of her on her lap. To her left, by her hands, is a quartered cantaloupe and a blue and white vase holding yellow flowers. She poses before a blue car that peaks out to her right. On the hood, a collection of fruit and a drink are evident.

In the background and to the right, a tall Black man, also in his 20s, stands, slightly turned to the right, in front of a yellow car. On his head, he wears a light purple durag cap that hangs down behind him. He also wears a gold chain and rings. His clothing is a medium purple jacket fastened with snaps, a gold symbol on the right chest. His trousers are white sweatpants, with the right leg pulled up just above his ankle socks, which are white with red and blue stripes. His shoes are white sneakers with black stripes.

The sky behind the figures and the ground are bright pink. A red smoke-like waft of air comes from the window of the yellow car and stretches across the horizon.

Adornment Section Introduction

Hi, I’m Elza Corrill, a security supervisor at the museum. I am introducing the Adornment section of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

“Now I like dollars/I like diamonds/I like stunting/I like shining,” Cardi B raps at the top of “I Like It.” Her words capture the recurrent identification of self with adornment in the canon of hip hop. While style often signifies class and politics, almost no culture dresses as self-referentially—or as influentially—as hip hop. From Lil’ Kim’s technicolor wigs to the exuberant, excessive layering of gold chains by Big Daddy Kane and Ra Kim, some of the most important and unique styles have originated in hip hop.

Jewelry flashes, grills glint in smiling mouths, and iconic Air Force One sneakers are meant to be seen. In her 2015 book Shine, art historian Krista Thompson looks at how light is caught and styled close to the body within the African Diaspora. She explores the ways people today “use objects to negotiate and represent their personhood,” in contrast to how their ancestors were defined as property. Adornment in hip hop culture can resist Eurocentric ideals of beauty and challenge concepts of taste and decorum.

What story does your style tell?

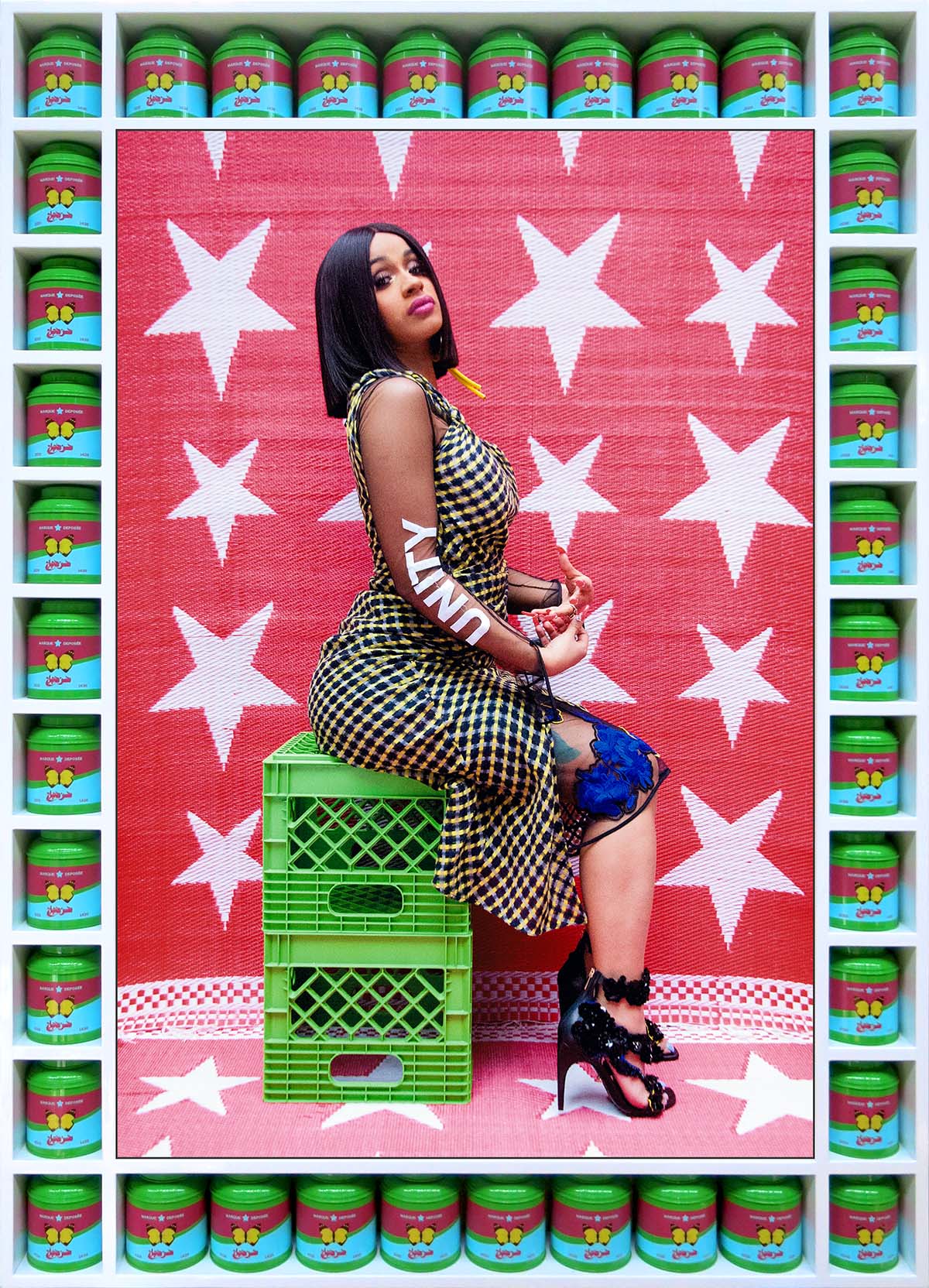

Black Power Artwork

Hank Willis Thomas (American, b. 1976, Plainfield, NJ), Black Power, 2006, Chromogenic print, Barret Barrera Projects, © Hank Willis Thomas

Black Power Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Elza Corrill, a security supervisor at the museum. I am sharing a description of Black Power, by Hank Willis Thomas in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21stst Century.

Hank Willis Thomas is an American artist born in 1976 in Plainfield, New Jersey. He created the Chromogenic print photograph, Black Power, in 2006. It is in the collection of Barret Barrera Projects. Hank Willis Thomas owns the copyright.

Black Power is a horizontally oriented color photograph measuring 21 and three-quarters by 30 and one-quarter inches or 55.2 by 76.8 centimeters. Here, the artist Hank Willis Thomas captures an extreme close-up image of a Black man’s smiling mouth. Around his lips, black stubble is evident. On his teeth, a diamond and gold grill with the words “Black Power!” is the focus of the image.

Tribute Section Introduction

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing the introduction to the Tribute section of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

From name-dropping in a song to wearing a portrait of a deceased rapper on a T-shirt, tributes, respects, and shout-outs are fundamental to hip hop culture. These references proclaim influence and who matters, honor legacies, and create networks of artistic associations. Elevating artists and styles contributes to hip hop’s canonization—when certain artworks, songs, and rappers are collectively recognized for their artistic excellence and historical impact.

Hip hop as a global art form has become a touchstone for artists of the twenty-first century. As visual artists trace its conceptual and social lineage through tribute, they engage the idea that the art historical canon, previously homogenous, white, and stable, is fluid depending on your background and preferences, questioning what is beautiful, who is iconic, and whose histories are valued.

Who do you pay homage or respect to in your life?

Heir to the Throne Artwork

Derrick Adams (American, b. 1970, Baltimore), Heir to the Throne, 2021, Non fungible token, Private Collection

Heir to the Throne Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing a description of Heir to the Throne by Derrick Adams in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Derrick Adams is an American artist born in 1970 in Baltimore, Maryland. Created in 2021, Heir to the Throne is a Non fungible token. It is in a Private Collection.

In the painting Heir to the Throne, artist Derrick Adams responds to musician Jay Z’s Reasonable Doubt album cover. In collaboration with the rapper, Adams transformed his painting into a nonfungible token video that runs 11 minutes. The painting is broken into thirds vertically. The image on the left is of a Black man wearing a black fedora-style hat with a white band, a black suit and shirt, and a white tie. Around his neck hangs a long white scarf. He holds a burning cigar in his right hand, which is adorned with a diamond bracelet. In the center image, the same man appears again, but the image is much closer to the figure. We see the top of his hat, down-turned face, and chest. He holds his right hand to the brim of his hat, on which a “25” is written in the smoke from the cigar. He continues to hold the burning cigar, and a diamond band is evident on his pinky finger. The final image of the same man shows him putting his hands together in a prayer pose, diamonds around both pinky fingers, and a diamond watch on his left wrist. The brim of the hat from the center image extends into this section.

In the NFT version of this work, Adams animates his painting to an illuminating and sparkling effect. The smoke from the cigars drifts throughout the image, and the diamonds on the subject's hands and wrists twinkle with a bright glow. The “25” on the hat drifts in and out with the wafts of smoke.

Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie) Artwork

Roberto Lugo (American, b. 1981, Philadelphia), Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie), 2019, Glazed ceramic, Collection of Peggy Scot and David Teplitzky, © Roberto Lugo. Photo: Neal Santos, courtesy Wexler Gallery

Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie) Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing a description of Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie) by Roberto Lugo in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Roberto Lugo is an American artist born in 1981 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His glazed ceramic vessel, Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie), was crafted in 2019. It is in the Collection of Peggy Scot and David Teplitzky. Roberto Lugo owns the copyright. The photo is by Neal Santos, courtesy of the Wexler Gallery.

Street Shrine 1: A Notorious Story (Biggie) is a large, colorful ceramic vessel measuring 54 by 27 by 27 inches or 137.2 by 68.6 by 68.6 centimeters. Roberto Lugo created a rounded lidded vase with a domed lid and narrowed footwhich he lavishly painted. Moving from the top to the bottom of the vessel, the white domed lid is decorated with blue flowers and swirls and has a blue pointed knob on top. The blue-on-white decoration continues as we proceed down the vase's body. In the center of the top half of the vessel, a three-quarter profile portrait of the rapper, The Notorious B.I.G. or Biggie, serves as the focus of the work. He wears a light-colored cap and large black sunglasses. The remainder of the vase is decorated with an arched shape in yellow and black with floral-like swirls and a Greek-key pattern. Lugo paints the lower portion of the work to resemble an ancient Greek red-ware vase.

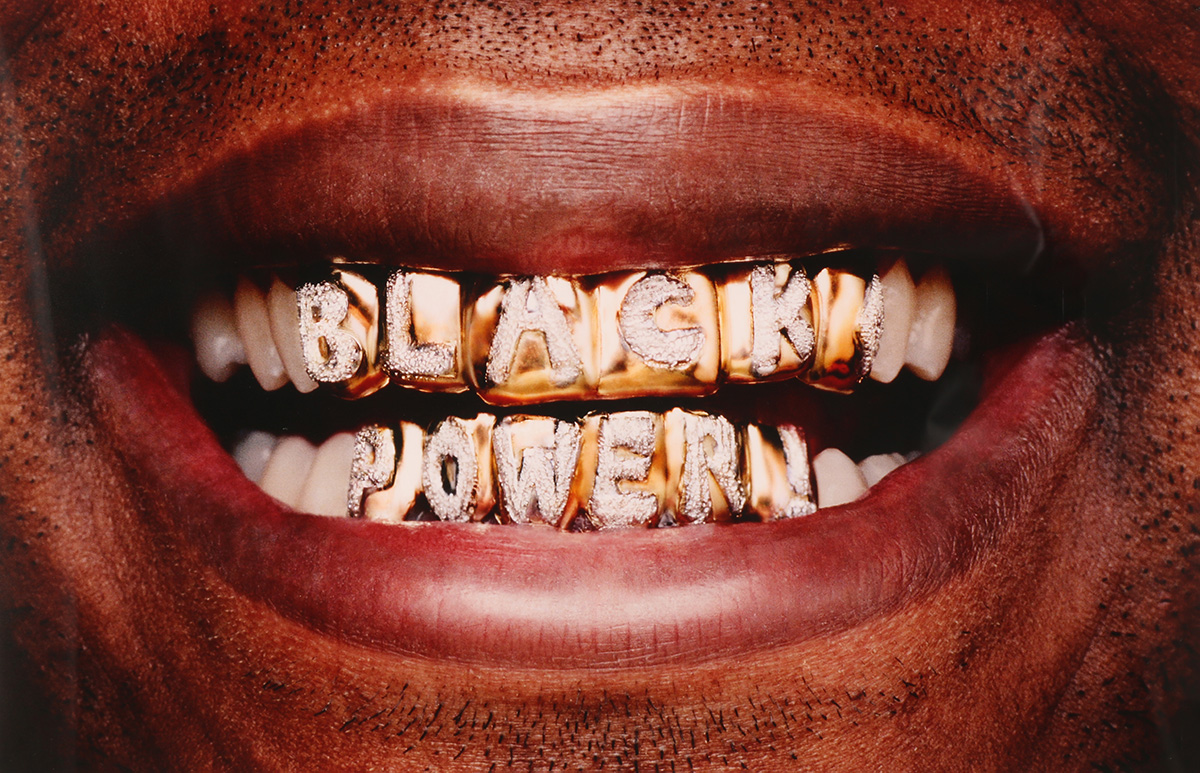

Seta's Room 1996 Artwork

Tschabalala Self (American, b. 1990, New York City), Seta's Room 1996, 2022, photo transfer, paper, acrylic paint, thread and painted canvas on canvas, Courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corris, London, © Tschabalala Self

Seta's Room 1996 Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing a description of Seta’s Room 1996 by Tschabalala Self in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Tschabalala Self is an American artist born in 1990 in New York City, New York. Seta’s Room 1996, from 2022, is photo transfer, paper, acrylic paint, thread, and painted canvas on canvas. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corris, London. Tschabalala Self owns the copyright.

Seta’s Room is a multi-media vertically oriented work measuring 96 by 84 inches or 243.8 by 213.4 centimeters. In this painting, the artist, Tschabalala Self, uses collage to create her scene. In the center of the work, a Black woman in her late teens or early 20s sits cross-legged on a brown wood plank floor. Her left leg tucks beneath her, and her right, with a bent knee, extends slightly out so her foot rests on the floor near a wooden stool. Her left arm is outstretched to her side, her hand resting on the floor. She holds a corded white phone receiver almost to her right ear in her right hand. The base of the phone sits on the short wooden stool to her right, as mentioned before. The young woman has a chin-length black bob-style haircut. She tilts her head slightly to her left, and she is smiling. She is wearing a red bikini with black polka dots. Her toes and fingernails are painted bright yellow. The pink wall behind her is unadorned except for a poster of the rapper Lil’ Kim.

Seta's Room 1996 Label

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing the label for Seta’s Room by Tschabalala Self in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Tschabalala Self is an American artist born in 1990 in New York City, New York. Seta’s Room 1996, from 2022, is photo transfer, paper, acrylic paint, thread, and painted canvas on canvas. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the artist and Pilar Corris, London. Tschabalala Self owns the copyright.

A young woman in a two-piece pink polka-dot outfit sits on the floor. She holds a landline phone in her hand as her smiling gaze looks beyond the picture frame. The artist, Tschabalala Self, based this work on recollections of her sister Princetta, who Self acknowledges as an important early muse.

The pink walls and hardwood floor recall Princetta’s teenage bedroom in the family’s Harlem, New York, brownstone. A Lil’ Kim poster—a promotional image for her 1996 debut album Hard Core—floats on a wall above the scene. This poster was significant to the artist, who credits it as a formative touchstone for her interest in how society situates the Black female body within contemporary Black culture.

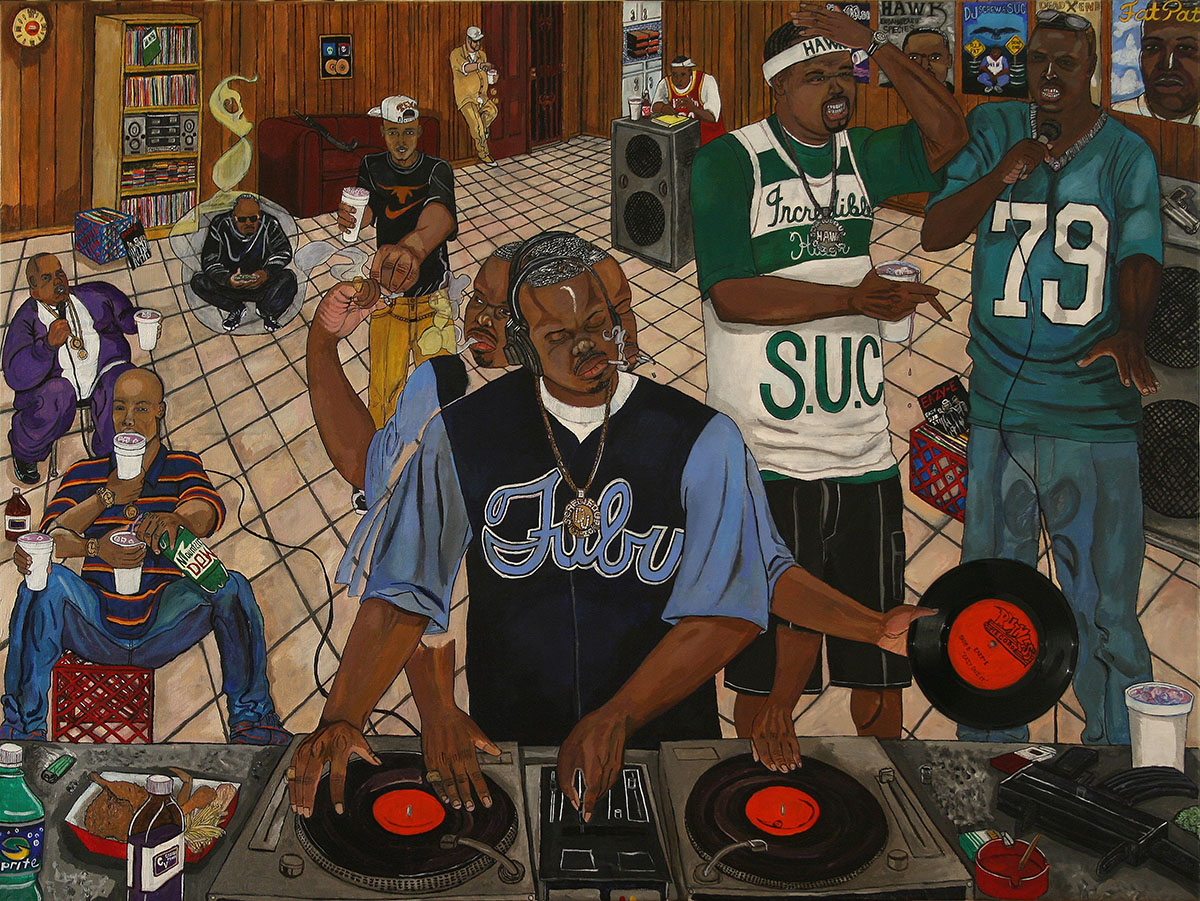

DJ Screw in Heaven Artwork

El Franco Lee II (American, b. 1985, Houston), DJ Screw in Heaven, 2008, acrylic and vinyl record on canvas, Private Collection, Houston, 38x48 inches (96.5x121.9 cm)

DJ Screw in Heaven Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing a description of DJ Screw in Heaven by El Franco Lee II in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

El Franco Lee II is an American artist born in 1985 in Houston, Texas. His painting, DJ Screw in Heaven, from 2008, is acrylic and vinyl record on canvas. It is in a Private Collection in Houston, Texas.

DJ Screw in Heaven is a multi-media horizontally oriented painting with a vinyl record measuring 38 by 48 inches or 96.5 by 121.9 centimeters. In this work, artist El Franco Lee the Second portrays DJ Screw in an interior space resembling a den. The walls are clad in brown wood paneling, and light tan tiles cover the floor. Several posters hang on the wall in the background and to the right, representing various performers. In the background on the left, a five-shelf unit holds records and a boombox-style stereo; in front of it, a blue plastic milk crate holds additional records. To the right of the shelf is a red couch above which a framed gold record hangs. In the center background, a door is open, and a kitchen is evident.

In the midground of the painting, across the scene's width, several Black men of various ages stand, sit, squat, and lean. Some hold white to-go cups, others smoke, while a man in the back appears to be eating. Two hold microphones. They all wear casual clothing: shorts, jeans, T-shirts, sweats, and basketball jerseys.

In the foreground, the focus of the work, DJ Screw, stands in front of his record deck, on which two records sit. To show action, the artist gives three views of his head: turned to the right, tilted down to his left, and barely turned the left. On his head, he is wearing headphones. His eyes appear closed, and he holds a cigarette between his lips. He wears a blue shirt with “Fubu” written on the front. He has four arms, showing his movement while spinning records. One of these hands holds an actual record attached to the canvas. To the right and left of his decks are food, soda bottles, a cigarette ashtray, and an automatic rifle.

DJ Screw in Heaven Label

Hi, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning & interpretation. I am sharing the label for DJ Screw in Heaven by El Franco Lee II in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

El Franco Lee II is an American artist born in 1985 in Houston, Texas. His painting, DJ Screw in Heaven, from 2008, is acrylic and vinyl record on canvas. It is in a Private Collection in Houston, Texas.

Wearing a Fubu shirt and in the flow, DJ Screw (1971–2000) presides over his turntables. Fans and friends surround him in his home—an essential part of the 1990s hip hop scene in Houston, Texas. His hands appear to be in motion, scratching and changing records. DJ Screw is a hip hop legend who created the distorted “chopped and screwed” sound; he would chop the lyrics, slow the tempo of a song, and reduce the pitch. Additional lyrics, often freestyles by Houston-based rappers, were then layered over his tracks.

DJ Screw tragically died of an overdose in 2000. Houston-based artist El Franco Lee II drew on his interest in comic books to create a detailed tribute to the DJ in his element.

Ascension Section Introduction

Hi, I’m Debra Tarter, a gallery attendant at the museum. I am introducing the Ascension section of The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

“Promise that you will sing about me/I said when the lights shut off and it’s my turn,” Kendrick Lamar gently asks in his 2012 song “Sing About Me, I’m Dying of Thirst.” Death—or the specter of it—along with notions of ascension and the afterlife frequently appear in hip hop lyrics, from pouring one out for a friend who has passed to the precariousness of being Black in an urban environment and never knowing which day is your last to meditations on the kind of immortality conferred by fame.

Inspired by themes of ascent in the culture, artists create works that invite reflection. Ordinary objects transform into altars and monuments, and images of Black bodies melt into heavenly clouds. Hip hop is a cultural form artists use to process, grieve, and remember those lost.

Pause and reflect on the lives and experiences amplified by the works on view.

Open Artwork

Monica Ikegwu (American, b. 1998, Baltimore), Open, 2021, oil on canvas, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Myrtis, © Monica Ikegwu

Closed Artwork

Monica Ikegwu (American, b. 1998, Baltimore), Closed, 2021, Oil on canvas, Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Myrtis, © Monica Ikegwu

Open & Closed Verbal Description

Hi, I’m Debra Tarter, a gallery attendant at the museum. I am sharing a description of Open and Closed by Monica Ikegwu in The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.

Monica Ikegwu is an American artist born in 1998 in Baltimore, Maryland. Her paintings, Open and Closed, from 2021, are oil on canvas. They are in the exhibition courtesy of the artist and Galerie Myrtis. Monica Ikegu owns the copyright.

Open and Closed are vertically oriented paintings measuring 48 by 36 inches or 121.9 by 91.4 centimeters. In these works, artist Monica Ikegwu creates a portrait of the same young Black woman in front of a red background. In Open, the woman, who appears to be in her early 20s, stands slightly turned to the left, her head, with hair pulled back in a low ponytail, tilts to the right, looking down on the viewer. She wears a dark red cropped tank top with narrow straps, a black bra just peeking out, and leggings in the same color. A long-hooded puffer coat, also in dark red, hangs off her shoulders, which are bare. She holds her hands in front of her.

In Closed, the same woman, in the same clothing, stands turned to her right; she peers over her left shoulder, again looking down on the viewer. The red puffer coat has been pulled up to cover her, a hint of her bare left shoulder is evident. She holds her left hand just under her chin.