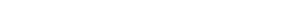

Whitfield Lovell: Passages Introduction

Whitfield Lovell: Passages, 2022, Editor: Michèle Wije, with essays by Cheryl Finley & Bridget R. Cooks, Publishers: American Federation of Arts & Rizzoli Electa, Dimensions: 9×11 1/2 inches, Format: Hardcover, 176 Pages, ISBN: 978-0-8478-7299-2

Hello, I’m Julie Aronson, the museum’s curator of American Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings and curator of the Cincinnati presentation of Whitfield Lovell: Passages. I will be sharing the introduction to the exhibition.

Whitfield Lovell has created a body of work that highlights the humanity of the Black subject and explores ideas around collective memory and events in American history. The faces depicted in the artwork in this exhibition were culled from Lovell’s collection of vintage photographs, which span the period from the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) through the Civil Rights Movement (1954–1968). Lovell imbues with new life these anonymous individuals whose identities are now lost to time. He often incorporates found objects into his drawings, such as playing cards, jewelry, rope, flags, and globes, to add another layer of significance to their visages.

Also central to Lovell’s art is music, which has inspired the titles of works throughout his oeuvre. Music plays a critical role in the two multisensory installations that anchor the exhibition: Deep River (2013) and Visitation: The Richmond Project (2001).

Lovell was born in the Bronx and continues to live and work in New York City. Exploring the major series in the artist’s career from the late 1980s to the present, Whitfield Lovell: Passages traces pivotal historic places and the beauty of everyday life.

All works unless otherwise noted are Courtesy of the Artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Deep River Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Deep River, 2013, fifty-six wooden discs, found objects, soil, video projections, sound, Dimensions variable, Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Deep River Introduction

Hello, I’m Julie Aronson, the museum’s curator of American Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings and curator of the Cincinnati presentation of Whitfield Lovell: Passages. I will be sharing the introduction to the Deep River installation in the exhibition.

In Deep River, a harmony of sounds and rich, earthy aromas precede the viewer’s awareness of the work’s powerful visual elements, perceived only after adjusting to the space’s dim light. Lovell’s first video installation, this monumental, multisensory work allows one to travel through time and space and ultimately transcend historical specificity. The inspiration for Deep River was the experience of countless enslaved African Americans who braved the perilous journey across the Tennessee River seeking asylum during the Civil War. Many found refuge from re-enslavement in “Camp Contraband,” the Union army encampment in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

The river here is a formidable force of nature that can be both destructive and benign. Its enveloping presence conveys a sense of eternal motion. The water surrounds a large mound of rich soil embedded with utensils, pans, lamps, ropes, boots, weapons, and a Bible to represent items abandoned during the flight toward freedom. Fifty-six wooden discs encircle the mound, each depicting a person of unknown identity. These subjects are not limited to Civil War-period figures; they represent a variety of eras, acknowledging that freedom and its pursuit are ongoing processes.

Please move carefully through the spiral configuration as you contemplate Deep River.

Deep River Description

Hello, I’m Julie Aronson, the museum’s curator of American Paintings, Sculpture, and Drawings and curator of the Cincinnati presentation of Whitfield Lovell: Passages. I will be sharing a description of Deep River.

Deep River, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2013. It is made from fifty-six wooden discs, found objects, soil, video projections, and sound. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

Deep River is a multi-media installation in a rectangular space the size of a ballroom. Black curtains surround the entrance to the room, and the low light has the muted effect of the outdoors bathed in moonlight. Text appears on a wall to the right of the entrance that reads: “During the Civil War, many of those escaping enslavement made the dangerous journey across the Tennessee River to a Union Army site referred to as ‘Camp Contraband.’ There, they were given asylum and shielded from being captured or returned to their owners.” Projected on the walls of the space, at an enormous scale, are videos of moving water that make you feel surrounded by it. The rippling water is a silvery blue green with bright, sparkling reflections and dark shadows. An old wooden spindle-back chair is mounted to one of the walls on which the water appears. Soft vocal music contributes to the moody atmosphere.

In the space’s interior, arranged in a spiral, are 56 weathered, wooden drum-shaped foundry molds, or tondos, as the artist calls them. The tondos, which vary in size from 10 to 78 inches in diameter, sit on their curved rims, looking like wheels that could roll away. On the flat, circular, vertically oriented surface of each tondo, facing the center of the room, is a portrait of a dark-skinned man or woman carefully drawn and shaded in black conté crayon. The artist left the mellow, honey tones of the wood as the background.

und of the portraits, and some show remnants of old paint or dings due to wear. One has nails protruding from the surface. Some of the tondos are rotated so the portraits appear tipped at an angle or upside down. The backs of the tondos reflect their earlier industrial use as molds. Their cut-out patterns differ, some featuring concentric circles.

Most of the portraits the artist drew on the tondos depict only the head or head and shoulders. Nine faces are in profile, while most are frontal or turned to various degrees. The larger tondos portray three quarter- or full-length figures, a few including a chair or table. A full-length portrait of a standing woman in a long dress with a full skirt is on the largest tondo. Across the 56 portraits, the dress and hairstyles vary, representing fashions from the late nineteenth-century through the 1960s. The men wear coats and ties. The women’s clothing ranges from puff-sleeved chemises and gowns to more form-fitting designs. Twelve of the people wear hats in a range of styles.

The spiral arrangement of the tondos encourages you to follow the path formed between rows until you come to the center. There, on the floor, is an oblong mound of dark brown soil measuring about 18 feet long by 8 feet wide by 14 inches deep at the center. Sitting in the soil, interspersed across the mound, is an array of well-used objects. Among these are a pair of men’s leather lace-up work boots, a trumpet, a large padlock, a chain with a hook at the end, ropes, a hatchet, a knife, a rifle, a pistol, a bucket, glass bottles, a copper coffee pot, spoons, a closed daguerreotype case, a lantern, a book of spirituals, and a Bible.

Prologue: Works on Paper Section Introduction

Hello, I’m Cynthia Collins, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing the introduction to the “Prologue: Works on Paper” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Lovell traveled widely as an art student in the 1980s and received his Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from The Cooper Union School of Art in New York City. At the start of his artistic career, he visited Mallorca, Spain; Morocco; Venice, Italy; and Mexico, experiences that helped broaden his general knowledge of the world and led to his “Prologue” period of works on paper (1985–97). Lovell’s travels also sparked an interest in domestic architecture, reflected in his works of the 1990s and early 2000s featuring the home as a common motif. In House IV, a simple structure appears inside the mind’s eye of an unknown figure. This image marks a shift in subject matter and, eventually, in medium, as the artist next embarked on a series of drawings on walls inside homes, honoring previous residents. The Prologue series conveys the artist’s personal and emotional ideas, memories, and aspirations through haunting motifs including clothing, flora and fauna, and partial figural forms. These elements are often interwoven and seemingly float in the picture plane.

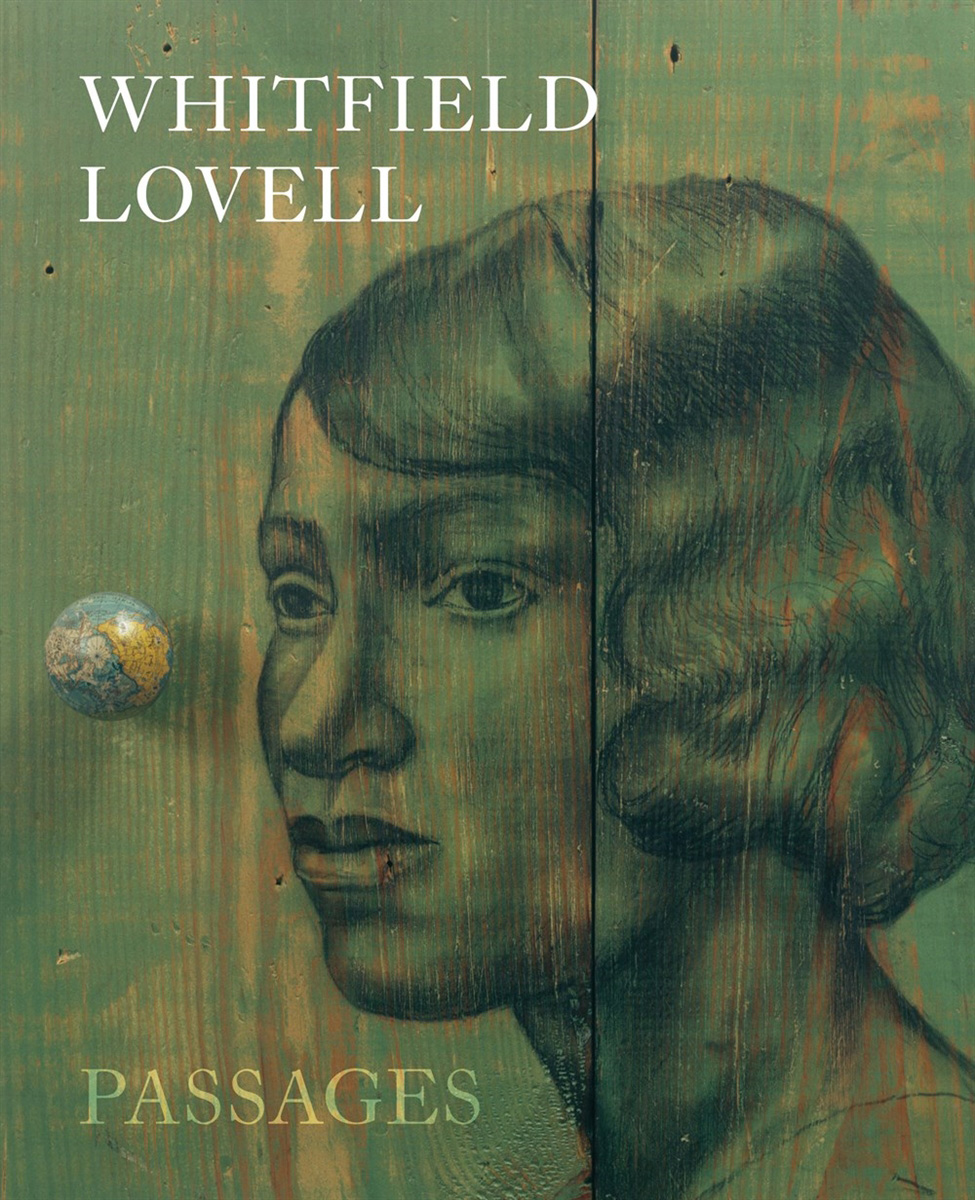

Head with Flowers Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Head with Flowers, 1992, Oil stick and charcoal on paper, 85 1/2 x 50 in, Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Head with Flowers Description

Hello, I’m Cynthia Collins, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing a description of Head with Flowers in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Head with Flowers, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 1992. It is oil stick and charcoal on paper. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

Head with Flowers is a vertically oriented oil stick and charcoal drawing on paper. This large work measures 85 and one-half inches tall and 50 inches wide. It is in the “Prologue” section of the exhibition, the first gallery you enter as you turn into the left side of the exhibition. In this drawing, the artist fills the central portion of the composition with a tall, triangular mass of flowers and leaves, wider at the base, stretching nearly to the left and right edges of the paper, and narrowing to a point near the top of the work. At the apex of the floral form, a hairless, egg-shaped head rests in a tilted position with closed eyes and mouth as if sleeping. The flowers and leaves in the triangular mound are in shades of black, white, and gray and represent numerous floral varieties—from roses to chrysanthemums and lilies. This composition is set upon a dark purple background that shifts to a lighter lilac color, providing an aura around the flowers and head.

Kin Series Section Introduction

Hello, I’m Linda Meador, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing the introduction to the “Kin Series” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Created between 2008 and 2011, Lovell’s Kin series comprises 60 works on paper that combine tenderly rendered likenesses of Black women or men with vintage objects. Each image appears with a high degree of realism, yet Lovell’s hand is still apparent in the careful shading and gritty textural quality of the subjects’ visages. The complex emotions Lovell captures in each face in the series invite the viewer to contemplate the humanity and singularity of every individual.

Lovell derived these likenesses from his carefully assembled collection of more than three thousand government identification photographs and photo-booth pictures dating from 1850 to 1950. In depicting real people from the past, each work represents a life lived. Lovell brings his subjects into the viewer’s space by juxtaposing each face with a found object. These objects bring color to the drawings, both literally and metaphorically. Lovell’s carefully chosen objects, worn from the use and touch of their previous owners, imbue the works in this series with a further sense of reality, tactility, and poetry.

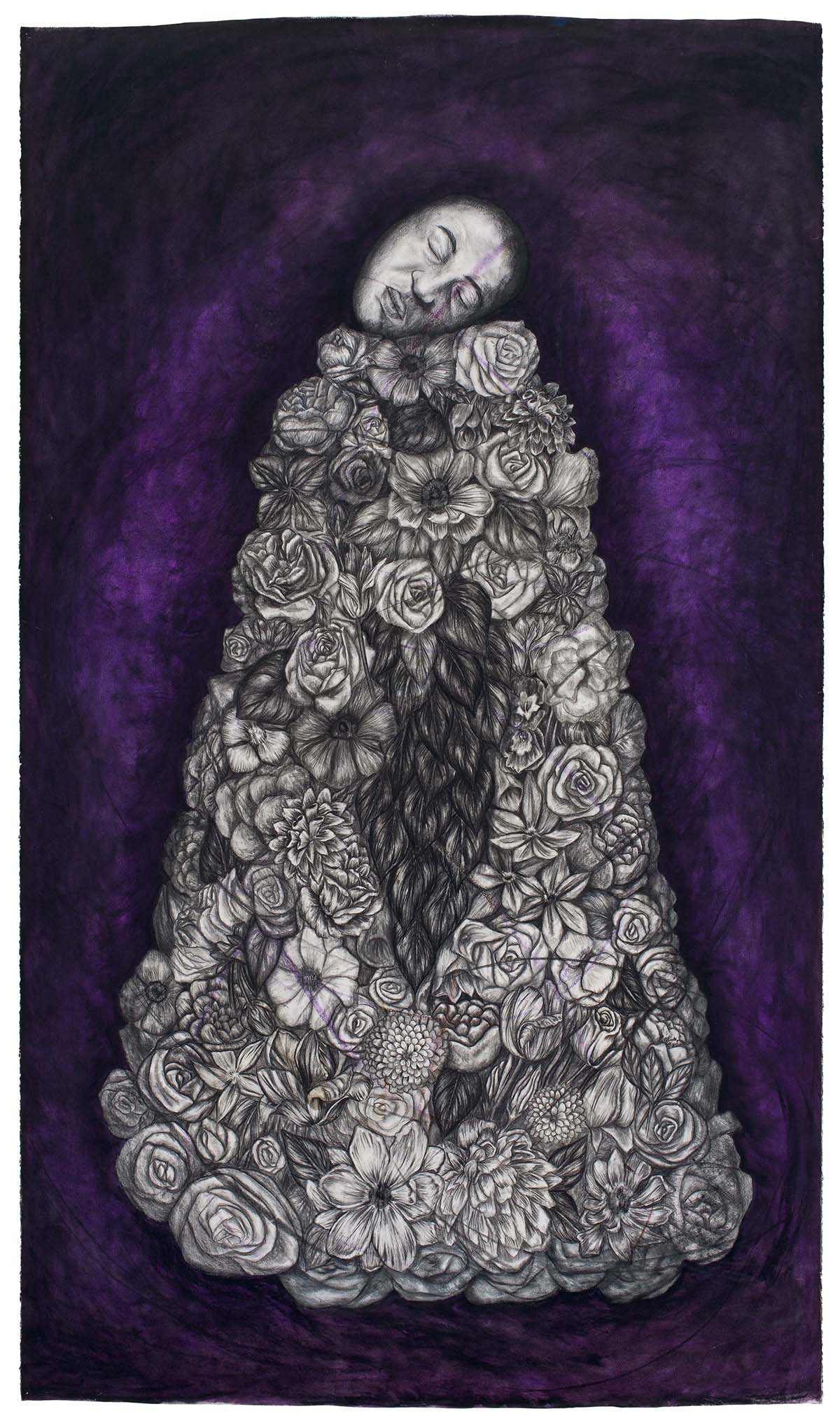

Kin I (Our Folks) Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Kin I (Our Folks), 2008, conté on paper, found paper flags, string, 30 x 22 1/2 in., Collection of Reginald and Aliya Browne, Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Kin I (Our Folks) Description

Hello, I’m Linda Meador, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing a description of Kin I (Our Folks) in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Kin I (Our Folks), by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2008. It is conté on paper with found paper flags and string. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

The drawing and collage, Kin I (Our Folks), is in the “Kin” section on the left side of the exhibition in Gallery 232. This space has two parallel entrances along the left wall of the larger gallery, creating a room within the exhibition. This conté on paper drawing includes an applied string of small found paper American flags and measures 30 inches by 22 and one-half inches. In the center of the blank cream-colored page is a detailed, gray-toned portrait of a dark-skinned young man’s head and shoulders. He wears a fedora-style hat set back on his head, so his entire face including his ears, is visible. His penetrating gaze looks intently at the viewer. His mouth is closed, with no evidence of a smile or a frown. His forehead and the tops of his cheeks are strongly illuminated. As we move down the page, the artist has lightly sketched in the outlines of the collar of the man’s shirt. Arranged in a jumble where his chest would be, a string of paper American flags is adhered to the work.

Kin XXV (River Run) Artwork

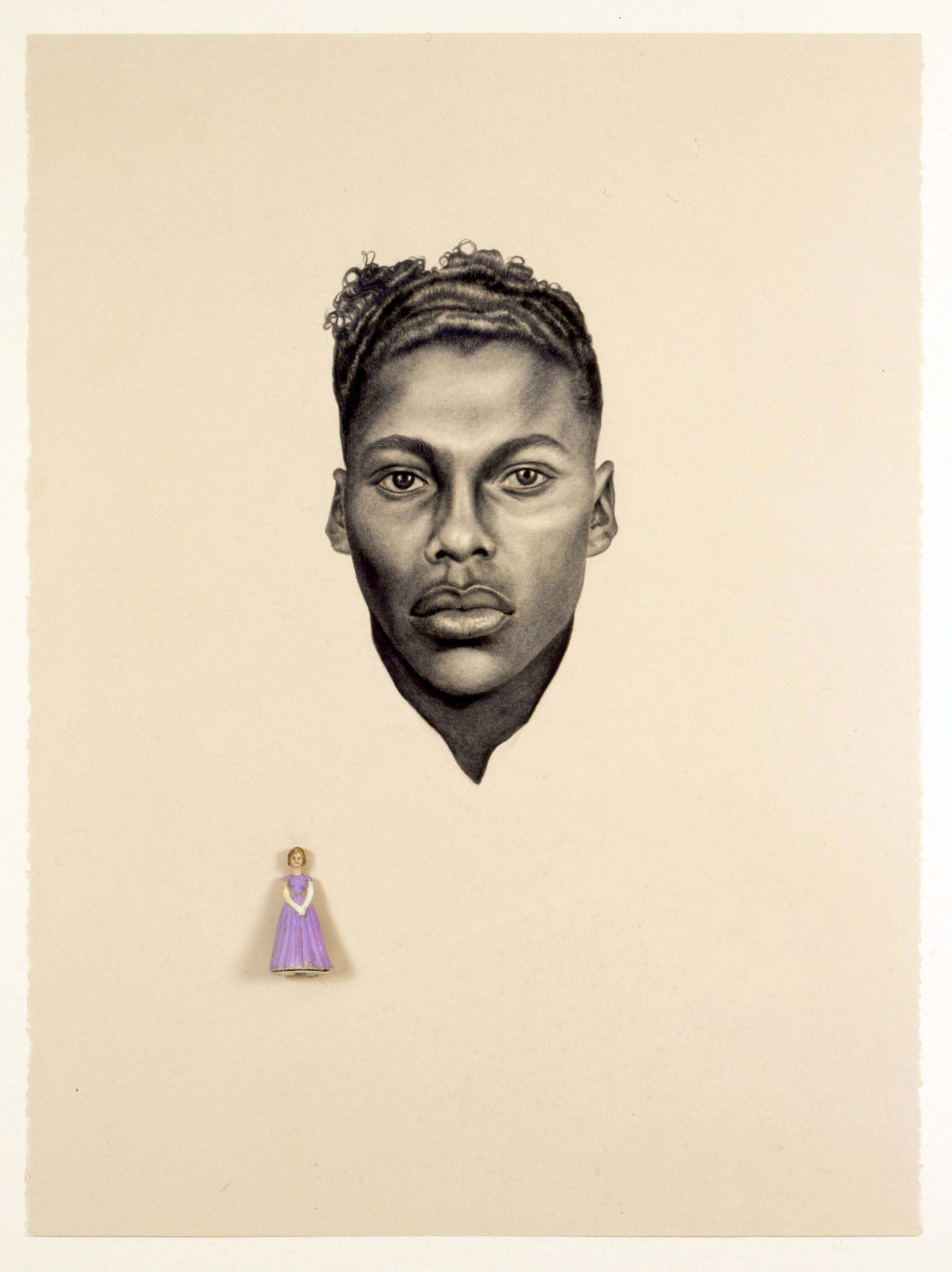

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Kin XXV (River Run), 2008, Conté on paper, plastic figurine, 30 x 22 1/2 x 1 1/4 in., Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Kin XXV (River Run) Description

Hello, I’m Linda Meador, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing a description of Kin XXV (River Run) in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Kin XXV (River Run), by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2008. It is conté on paper with a plastic figurine. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

Kin XXV (25) (River Run) is a vertically oriented conté on paper drawing and collage. It measures 30 inches by 22 and one-half inches by one and one-quarter inches. It is in the “Kin” section on the left side of the exhibition. This space has two parallel entrances along the left wall of the larger gallery, creating a room within the exhibition. In shades of black and gray on cream-colored paper, the artist has drawn the head and neck of a young dark-skinned man who is likely in his twenties. The drawing is hyper-realistic, almost photographic, and startling against the large expanse of blank paper around it. With short curly hair that waves back off his forehead, the man has an intent gaze focused directly on the viewer. His mouth is closed; he is neither smiling nor frowning, yet his expression is serious. His ears, which are evident, are small and slightly bent back toward his head. Attached to the work, below and to the left of the portrait, is a small figurine of a light-skinned young woman in a purple ball gown with capped sleeves and long white gloves that extend above her elbows.

Visitation: The Richmond Project Section Introduction

Hello, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning and interpretation. I will be sharing the introduction to the “Visitation: The Richmond Project” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

In 1903, Maggie L. Walker founded St. Luke Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, Virginia’s Jackson Ward, making her the first woman and the first African American to start a bank. She, along with other community members before and after, turned Jackson Ward into one of the most active and well-known centers of African American entrepreneurship in the United States. This installation, made in 2001 during a six-week residency in Richmond, features the story of the inhabitants’ struggle for emancipation and their collective efforts to overcome the legacy of enslavement.

Visitation: The Richmond Project is in five parts: Battleground, Restoreth, Our Best, Coins, and Visitation: The Parlor. Immersing himself in his environment, Lovell pursued research in regional photographic archives and worked with university students to construct this installation with locally sourced materials. While the figures represent people from the Civil War to the early twentieth century, a woman’s voice softly recites the names and addresses of the residents of Jackson Ward published in a 1917 NAACP application for city charter. Boxes of Lincoln pennies in Our Best symbolize Walker’s Penny Savings Bank and refer to President Lincoln’s role in emancipation. The faces on Coins recall those of presidents on American currency yet represent everyday individuals from Jackson Ward. Restoreth symbolizes the tradition of matriarchs as practitioners of folk medicine. Lovell has said of Visitation: The Richmond Project, “I want to evoke a sense of place, to be able to feel the spirit of the past for a moment, to feel the presence of these people.”

Visitation: The Richmond Project

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Visitation: The Richmond Project, 2001, Parlor, dining table, organ, various objects, wooden walls 223, 1/4 x 161 3/4 in., Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Visitation: The Richmond Project Description

Hello, I’m Emily Holtrop, the museum’s director of learning and interpretation. I will be sharing a description of Visitation: The Richmond Project, Parlor in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Visitation: The Richmond Project, Parlor, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2001. It includes a dining table, an organ, various objects, and wooden walls. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

The Parlor is one of five components of the immersive installation called Visitation: The Richmond Project and combines drawings on the walls with found, three-dimensional objects. You enter the parlor through a pair of cream-colored, semi-transparent curtains. The windowless room is about 18 feet long by 13 feet wide with old, unpainted, wood-paneled walls and a planked-wood floor. The lighting is dim, illuminated by a warm lamplight.

At the center of the room is a small, rectangular dining table with an off-white lace tablecloth and four mismatched wooden dining chairs, some plain and others with curved legs and a little ornament on the top rail. The chairs are variously angled to the table, which is set for four people with silverware and white dishes, each with an ornamental border and a central fruit motif. An empty white platter is in the middle of the table.

Turning right when entering the room, you first encounter a small side table with a very distressed red surface, possibly leather, on which sits a ring of keys and a clock with a wood case and a gold-colored metal ornament above a round white dial. Flanking the dial are two columns with leafy gold-colored metal capitals. The clock has Roman numerals, and the time is 6:45. On the table’s bottom shelf are glass bottles. To the right of this table, near the right front corner of the room, are about half a dozen wooden walking canes clustered together and leaning against the wall.

Moving around the room’s perimeter to the right-hand wall, we come to a life-size figure of a standing Black man drawn directly on the paneling with a black conté crayon. The careful drawing is realistically shaded, with exposed paneling in the lighter areas. Looking straight out towards us, the man has close-cropped hair that comes to a “v” in the center of his forehead, and he wears a dark suit with a lighter vest and dark necktie. He tucks his right hand into the pocket of his loose-fitting trousers while his left rests at his side.

To the drawn man’s left is a small one-drawer desk with a curved back rail and a letter holder at each corner filled with several envelopes. On the desk are arrayed objects including fanned-out envelopes addressed and postmarked, a pen, an inkwell, a book with Give Us Our Dream printed on the cover, a pair of pince-nez glasses, a goblet, an oil lamp filled with red liquid, a brown glass bottle, a pipe, a cigar, tobacco tins (the largest of which is partially opened and filled with tobacco), and a small dish holding extinguished cigarette butts.

Angled in the far-right corner of the room is a wooden chair with the back, arms, and seat upholstered in a green-gold tapestry-like fabric. We then proceed to the room's rear wall, opposite the door we entered, where a small table is arrayed with various glassware, including five goblets containing rose-colored liquid. Also on this table is a dish containing a cigarette butt and a small golden-shaded table lamp, turned on. A framed botanical print of a sprig of pink and yellow roses hangs above the table, and to the left is a door, slightly ajar and opening outward.

Around the corner against the adjacent wall, we come to an old arch-topped radio sitting on a small table covered with a lace tablecloth. Next to this is an organ with decorative fretwork panels above and below the keyboard and a music holder with a hymn book opened to the music for “Our Best.” Next to the music holder sits a pair of spectacles, and on top of the organ are a wooden clock with a round white dial indicating a time of about 6:50 centered between a glass oil lamp half filled with a clear pinkish-red liquid and a tall glass vase. A pile of crumbling old Richmond Dispatch newspapers with the partially visible headlines “King George,” “Prince,” and “New Monarchs” is on the piano bench.

To the left of the piano appears a life-size figure of a Black woman drawn lightly on the wall in black conté crayon. She faces to the front and raises her right hand to her waist while her left is down by her side. A broad-brimmed hat at a rakish angle casts a shadow across her eyes. Over a knee-length skirt, she wears a belted and slightly open coat with wide lapels. She holds what may be gloves in her hands.

In the adjacent corner of the room, positioned at an angle, is a stool with what looks like a black cast iron base, an army green seat, and gold fringe. Several feet to the left is an illuminated electric floor lamp with a twisted metal pole rising from a pierced, clover-leaf-shaped, gold-toned metal base. The lamp, which emits a mellow light through its yellowed shade, stands next to a round pedestal table. A stack of white china with gold patterned edges sits on the table in front of a tall, straight-sided, white china pitcher with a blue scalloped rim and an enormous pink rose on its body. A dull silver metal sugar bowl and a creamer with fancy curved legs appear at the left of the plates, and a silver-colored cake server is at their right.

We move to the left to exit through the same curtained door we entered.

The Reds Section Introduction

Hello, I’m Myra Paige Livingston, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing the introduction to the “The Reds” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

While on an extended trip to Italy in 2021, Lovell created his assemblages in The Reds series on luscious, deep-red paper. Whereas red may evoke warmth, passion, and vibrancy, it is also associated with fire, danger, and blood. The individual works of The Reds appear alongside The Anthem Phone 2. The artist has repurposed this antique telephone table, sometimes called a “gossip bench,” with red upholstery and a rotary telephone from which plays a stirring vocal rendition of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” The hymn, written in 1900, speaks of the hopefulness of many Black people at that time, who believed they were at the dawn of a new era and headed toward the goal of achieving equality. In 1917, the NAACP began referring to the hymn as the Black national anthem, which served as inspiration for Lovell’s title of this work.

The Red I Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), The Red I, 2021, conté on paper with attached found object 45 3/4 x 34 x 5 7/8 in., Courtesy American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Red I Description

Hello, I’m Myra Paige Livingston, a member of the museum’s Donald P. Sowell Endowment Committee. I will be sharing a description of The Red I in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

The Red I, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2021. It is conté on paper with an attached found object. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

Upon leaving the “Visitation: The Richmond Project” section at the end of Gallery 232, you will turn right and find yourself in “The Reds” section. This space has two parallel entrances along the left wall of the larger gallery, creating a room within the exhibition. The Red I, is a vertically oriented drawing in conté crayon measuring 45 and three-quarter inches by 34 inches by five and seven-eighths inches in depth. In this work, the artist creates a detailed portrait in shades of black of a dark-skinned young woman in a mid- to late-nineteenth-century dress. Set on a deep red paper that forms the drawing’s background, the woman wears a high-necked, long-sleeved gown with three vertical rows of buttons, a large rose just above her bosom, and vertical pleating on her skirt. She holds her right arm across her waist while her left hangs relaxed at her side. In her right hand, she holds a sprig with a flower and leaves. The woman’s head is slightly turned to the left, and her eyes gaze thoughtfully off the page; she is not looking directly at the viewer. Her black hair is in a simple updo with a center part and gentle waves at the front hairline. She wears small earrings that dangle from each lobe. The drawing is under glass in a deep-set black frame with a red liner in a darkershade than the paper. Attached to the drawing and overlapping the liner at the bottom and to the left of the portrait is a small circular black vase with a narrow neck and flared opening.

Tableaux Section Introduction

Hello, I Erin Carmichael-Morgan, coordinator of the Rosenthal Education Center. I will be sharing the introduction to the “Tableaux” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Starting in the late 1990s, Lovell began making stand-alone tableaux that blend his interests in drawing, assemblage, and memory. Traditionally, tableaux are scenes arranged for dramatic effect, usually within a clearly conceived narrative. Rather than reconstructing details of a complete story, however, Lovell intends to evoke the possibility of one. His tableaux convey a sense of visual poetry.

In these conceptual works, the artist combines charcoal drawings of individuals rendered on wooden planks with found objects that extend into the viewer’s space. Many of these works feature exquisite, highly finished figures who appear not so much drawn on their wooden surfaces as emerging organically from them. These images of anonymous individuals emanate a ghostly quality that suggests lives once lived but now past. Sourcing the images from vintage studio and other types of photographs frees Lovell from any attachments to the narratives of the peoples’ lives.

Because I Wanna Fly Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Because I Wanna Fly, 2021, conté on wood with attached found objects, Diam: 114 in., Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

Because I Wanna Fly Description

Hello, I'm Erin Carmichael-Morgan, coordinator of the Rosenthal Education Center. I will be sharing a description of Because I Wanna Fly in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Because I Wanna Fly, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2021. It is conté on wood with attached found objects. It is in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

The large, circular conté on wood assemblage, Because I Wanna Fly, dominates the gallery space, measuring 114 inches in diameter. While this work is part of the “Tableaux” section, it hangs adjacent to that section with works from “The Reds.” The artist made this drawing of a young woman directly on a flat disc made of wood planks so that the warm tan color of the wood and the grain show through the drawing. Here, we see a dark-skinned adult female in a high-necked, puffed-sleeved, full-skirted gown from the mid-nineteenth century. She wears three beaded necklaces of various lengths around her neck and small dangling earrings. Her black hair is pulled in a low bun at the nape of her neck and is swept away from her face in soft waves. She sits, with her full skirts splayed out in front of her, in an elaborate high-backed wood chair with twisted columns and a troll-like face carved on the back. Her body is nearly in profile, facing to the right, but her face turns to the front with a slight side-eyed gaze. She leans her left elbow on a small, round table covered with a cloth and a short skirt. Her left hand is raised almost to her chin as if she is about to rest her head on it. Her right arm is relaxed in her lap. Six life-size, three-dimensional, real-looking black birds on short branches face in various directions and surround this central figure. An empty perch sits just above and to the right of her head.

Because I Wanna Fly Label

Hello, I Erin Carmichael-Morgan, coordinator of the Rosenthal Education Center. I will be sharing the label for Because I Wanna Fly in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Because I Wanna Fly, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2021. It is conté on wood with an attached found object. It is in the collection of the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts.

Pictured in this circular tableau is a woman seated in a late-nineteenth-century Gilded Age chair surrounded by perched blackbirds. The work is a testament to the artist’s love of music and his friendship with the singer-songwriter and pianist Nina Simone. Lovell’s title is an homage to her 1963 song “Blackbird,” written in the form of a call and response, a tradition in African American music. Simone’s lyrics ask, “Why you wanna fly, Blackbird? . . . You ain’t ever gonna fly,” and Lovell’s retort is “Because I Wanna Fly.” The bold response evident in Lovell’s title imbues the central figure with a sense of personal agency and confidence.

America Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), America, 2000, charcoal on wood, 89 x 53 1/2 x 20 in., Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

America Description

Hello, I Erin Carmichael-Morgan, coordinator of the Rosenthal Education Center. I will be sharing a description of America in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

America, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2000. It is charcoal on wood with attached flags. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

America, a large charcoal-on-wood drawing with found objects, is in the exhibition’s “Tableaux” section, which spans the center of Gallery 232. Measuring 89 inches by 53 and one-half inches by 20 inches, this vertically oriented work is crafted from planks of wood cut into a flat oval shape and placed against the wall. The artist captures a realistic, life-size full-length portrait of a middle-aged, dark-skinned man in charcoal on wood planks, which are visible through the drawing. The man has short black hair, parted on the left, a fuller chin, a few facial lines, and a dark mustache. The man wears a dark business suit, a light-colored shirt, and a solid black necktie. He stands facing forward, his arms hanging at his sides. Applied to the work are five medium-sized American flags on small sticks with gold finials. These protrude and fan out from a central point in the composition around the man’s navel. A much larger flag hangs down from the cluster of small flags, covering the man’s legs and puddling on the floor in front of the work.

Crossroads Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), Crossroads, 2012, conté on wood with attached paperback books, 39 x 36 x 5 in., Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

Crossroads Description

Hello, I Erin Carmichael-Morgan, coordinator of the Rosenthal Education Center. I will be sharing a description of Crossroads in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

Crossroads, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2012. It is conté on wood with attached paperback books. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

Crossroads is a multi-media wall sculpture comprised of a conté on wood drawing and paperback books. This three-dimensional work hangs on the wall and measures 39 inches by 36 inches by five inches. It is in the exhibition’s “Tableaux” section, which spans the center of Gallery 232. In this work, the artist has created a “t” or cross shape from paperback books stacked vertically and horizontally. The spines of the books are against the wall, so their titles are unknown. The edges of the pages facing toward the viewer are different colors for each book: not only various shades of tan, but some are red, hunter green, or white. The arrangement of the books thereby creates a seemingly random striped pattern. As the books are somewhat different sizes, the edges of the cross form are irregular. Slightly larger books surround the center of the cross form, framing a square portrait of a middle-aged, dark-skinned woman with a black, wavy, chin-length bob haircut. The picture is conté on wood, with the medium brown of the wood evident through the drawing. The subject’s head, though turned very slightly to the left, faces the viewer, while her upper torso angles to the left. She looks out directly with neither a smile nor a frown on her face.

The Card Pieces Section Introduction

Hello, I'm Emma Hensley, the museum's tour coordinator. I will be sharing the introduction to the “The Card Pieces” section of the exhibition, Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

The Card Pieces utilizes an entire deck of vintage playing cards, including a joker. Each work consists of an individual’s face and a single playing card. The central positioning of both elements creates a grounded compositional format through which each takes on its own unique character. There is an implication of destiny, of chance, and of one’s lot in life.

The formal appearance and geometry of the cards interact with the features, expressions, and accessories of the people depicted. Lovell says, “When making The Card Pieces, the most exciting part of the process occurs when I deliberate, and carefully choose the card that best fits the drawn image. The pairing is intuitive, rather than formulaic.” The resulting juxtaposition of faces with the suits, symbols, and color on the cards alludes to psychological and sociological meanings concerning individuality, gender, and power.

A lively and thriving tradition of card games as a social activity within the African American community lends additional significance to the series.

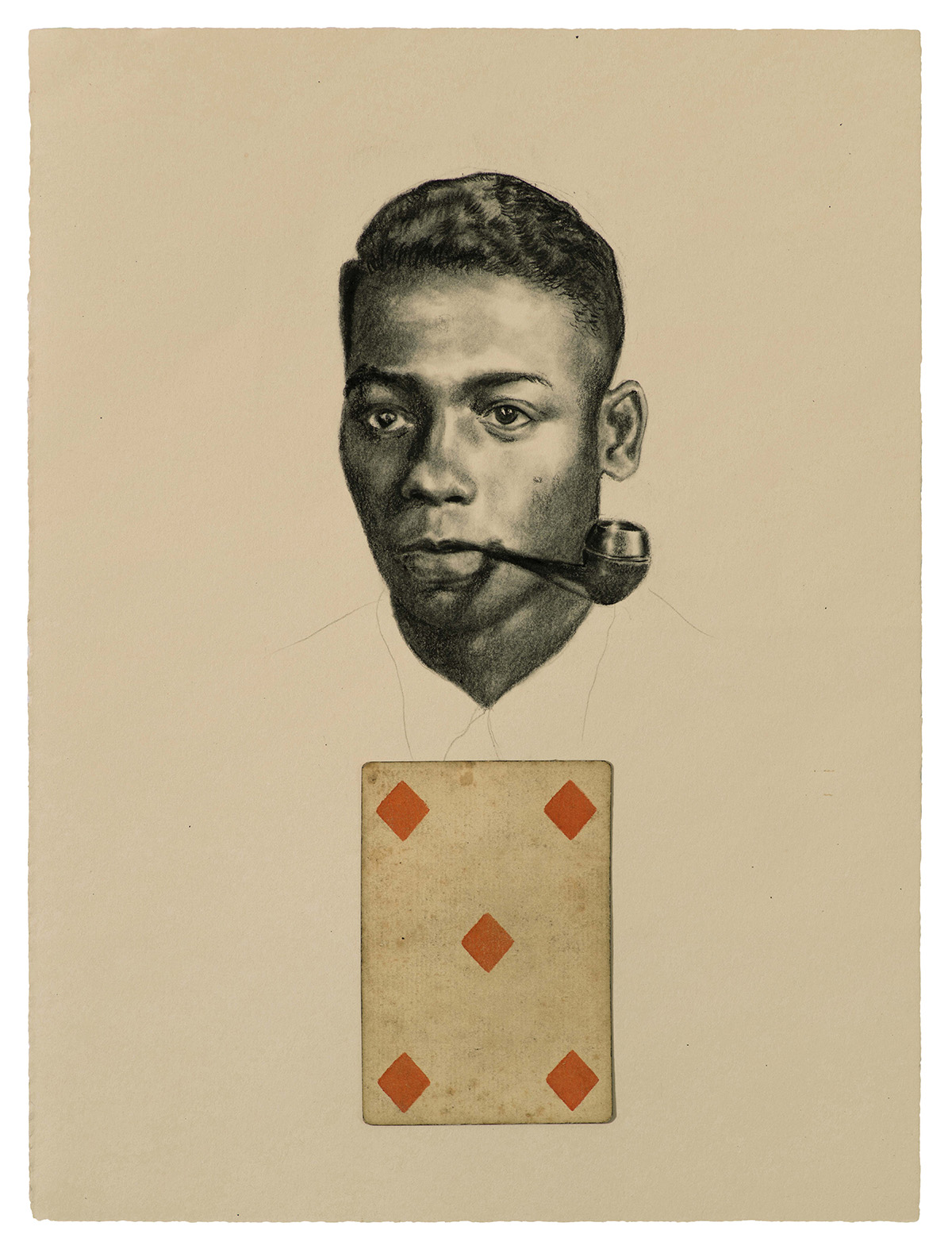

The Card Pieces Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), The Card Pieces, 2018–22, charcoal pencil on paper with attached playing cards, Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Card Pieces Description

Hello, I'm Emma Hensley, the museum's tour coordinator. I will be sharing a description of The Card Pieces in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

The Card Pieces, by the American artist Whitfield Lovell, dates from 2018 to 2022. The works are charcoal pencil on paper with attached playing cards. It is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

This work is one of 53 that make up The Card Pieces, tightly installed in the final space on the Gallery 232 side of the exhibition. Like each of the drawings in this series, it measures 12 inches by 9 inches and is charcoal pencil on paper. In this vertically oriented, realistically detailed drawing, the artist captures a young, dark-skinned man with short black hair combed back from his face and parted on his right. His head is angled so that only his left ear is visible. A drawn pipe projects straight out from the left side of the subject’s mouth. He does not look directly at the viewer but off to the left. The light source for the drawing illuminates his left eye and cheek. The artist has included a rough outline of a shirt collar at the base of the man’s neck. Below the portrait, a red four-of-diamonds playing card is attached to the drawing.

The Card Pieces Artwork

Whitfield Lovell (American, b. Bronx, NY), The Card Pieces, 2018–22, charcoal pencil on paper with attached playing cards, Courtesy of American Federation of Arts, the artist, and DC Moore Gallery, New York

The Card Pieces Description

Hello, I'm Emma Hensley, the museum's tour coordinator. I will be sharing a description of The Card Pieces in Whitfield Lovell: Passages.

The American artist Whitfield Lovell created The Card Pieces from 2018 to 2022. The works are charcoal pencil on paper with attached playing cards. This multi-part work is in the exhibition courtesy of the American Federation of Arts, the artist, and the DC Moore Gallery in New York.

This work is one of 53 tightly hung collages collectively called the “The Card Pieces,” displayed in the final gallery space on Gallery 232 side of the exhibition. Like each of the drawings in this series, it measures 12 inches by 9 inches and is charcoal pencil on paper. Here, the artist has captured an older, light-skinned Black woman. Her head tilts slightly to the right, and her gaze, behind round wire-rimmed glasses, is directly at the viewer. Her mouth is closed with a slight upturn to the lips into a small smile. A few lines appear on her face. Perched atop her short curly hair is a hat with a circular brim extending to her left and a large fabric bow, with a tail hanging near her eye, on her right. She wears a floral earring in her right ear, the only one visible in the drawing. Below the woman’s portrait, a black three of clubs playing card has been attached to the work.