- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Mexican Printmakers 1920s–1950s

Mexican Printmakers 1920s–1950s

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

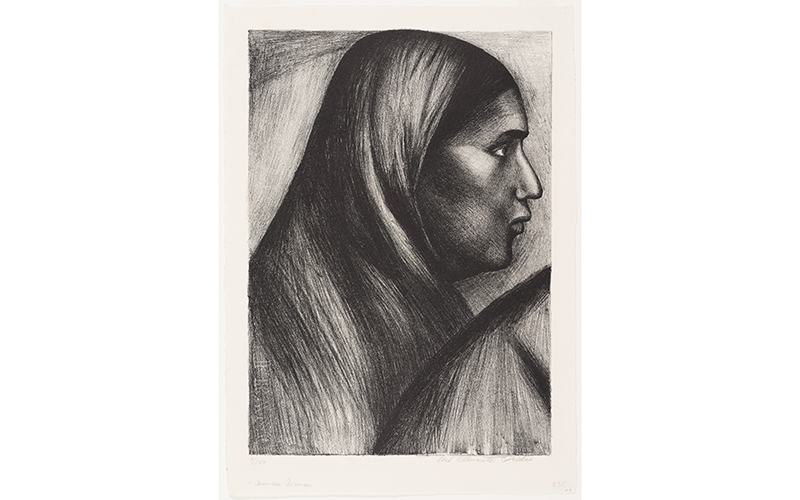

José Clemente Orozco (Mexican, 1883–1949), Mexican Woman (Mujer Mexicana), 1926, lithograph, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.411

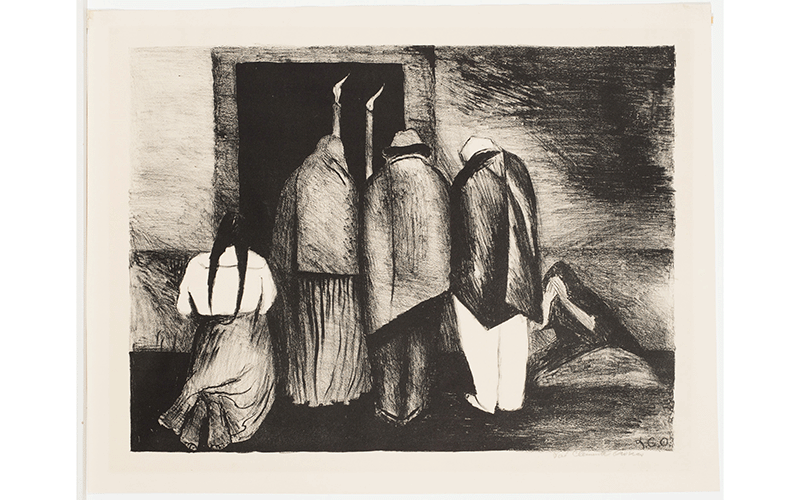

José Clemente Orozco (Mexican, 1883–1949), The Requiem (El Requiem), 1928, lithograph, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.410

José Clemente Orozco, (Mexican, 1883–1949), Tourists and Aztecs, 1934, lithograph, The Albert P. Strietmann Collection, 1960.801

José Clemente Orozco (Mexican, 1883–1949), Women, 1935, lithograph, Gift of Elaine and Arnold Dunkelman, 1982.24

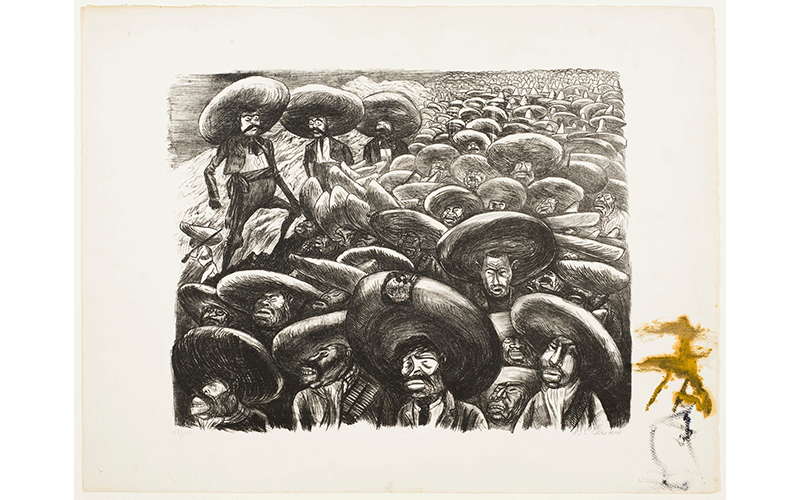

José Clemente Orozco (Mexican, 1883–1949), Zapatistas, 1935, lithograph, Gift of Elaine and Arnold Dunkelman, 1982.25

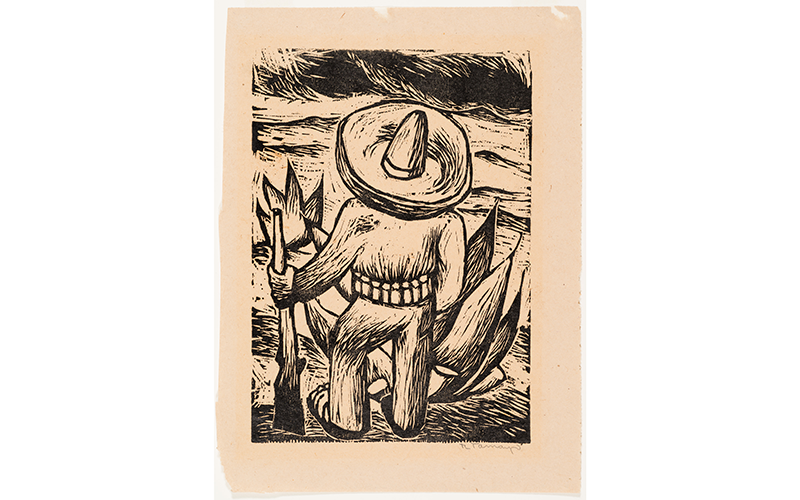

Rufino Tamayo (Mexican, 1899–1991), Mexican Peasants, 1929, linoleum cuts, Museum Purchase, 1931.69

Rufino Tamayo (Mexican, 1899–1991), The Revolutionist, 1931, linoleum cut, Museum Purchase, 1931.71

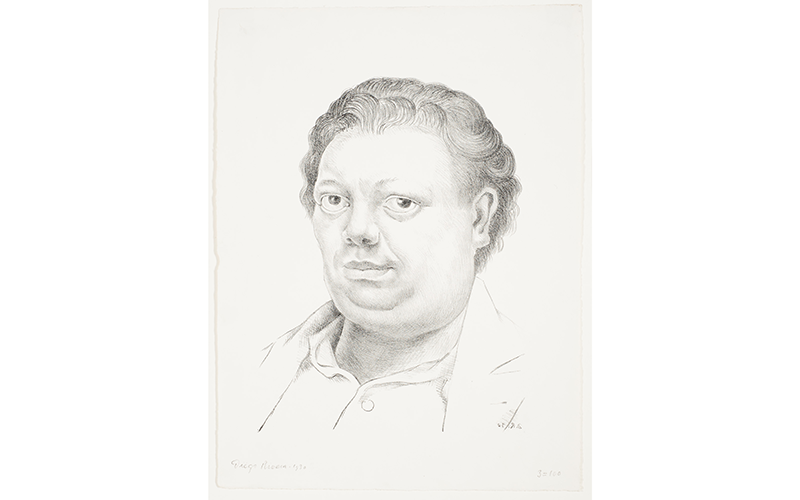

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886–1957), Self-Portrait, 1930, lithograph, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.450

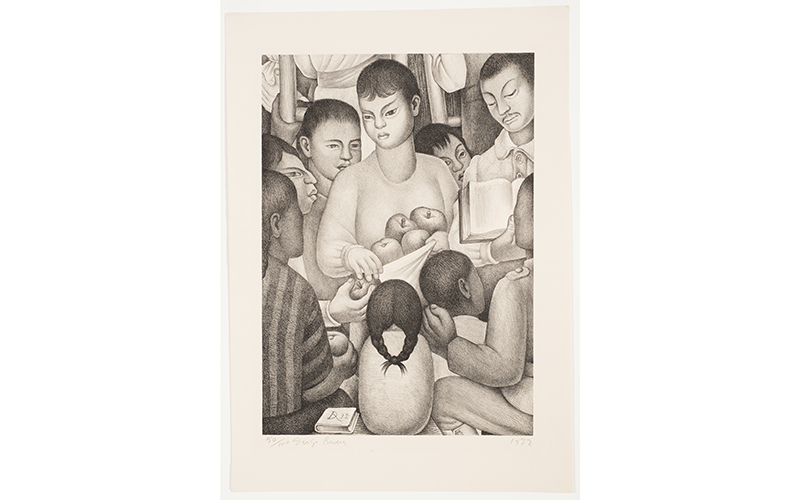

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886–1957), The Fruits of Labor, 1932, lithograph, Gift of Herbert Greer French, 1940.451

Mexican Printmakers 1920s–1950s

April 16, 2022–August 14, 2022

Gallery 213

One of the major social upheavals of the early twentieth century was the decade-long Mexican Revolution (1910–20). In the end, a constitutional republic replaced an entrenched dictatorship. During the post-revolutionary decades, as Mexican democracy began its difficult growth, a remarkable artistic outpouring followed. Through propagandist murals in public buildings and the distribution of printed images, art flourished as artists addressed the evolution of revolutionary ideas as outlined in the new constitution. Prints attacked Fascism and Imperialism, while promoting Indigenous rights, and educational and labor reform. Works also promoted and celebrated Mexico’s national heritage to educate the largely illiterate populace through visual storytelling. In the 1920s, murals by Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros and José Clement Orozco—“Los Tres Grandes” (The Great Three)— received international recognition. Spurred by their success they created prints as an effective means of raising social awareness.

A little-known fact is the extent to which American print publishers participated in the post-revolution Mexican print movement. The Weyhe Gallery in New York championed Mexican art by commissioning and exhibiting prints in the 1920s and 1930s. The earliest lithographs featured mural details related to the revolution, thus creating powerful symbols of national identity. Taller de Gráfica Popular founded in Mexico City in 1937 and Associated American Artists in the 1940s furthered the dissemination of Mexican printmaking. Participants created powerful genre scenes drawing attention to the struggles of Mexican life. The prints generated as part of the post-revolutionary movement strongly influenced American Regionalism and the WPA prints of the Depression-era.

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: