- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teen Immersive Workshop: Portraiture

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

A Long Tradition: Dragons in the East Asian Collection

by Eric Hughett, Curatorial Assistant of East Asian Art

4/16/2024

Year of the Dragon , Zodiac , East Asian Art

2024 is the Year of the Dragon, according to the 12-year cycle of the Chinese zodiac, which presents a perfect opportunity to look at Chinese dragons as a theme in East Asian art. What are the hallmarks of Chinese dragons? How have artists traditionally depicted them? Luckily, we can turn to the museum’s rich East Asian collection for help.

The mythical Chinese dragon (龍 lóng) first appeared in Chinese literature during the late Zhou dynasty (771–256 BCE). The Book of Changes (Yijing 易經) identified the dragon as a creature able to exist in and travel between all three realms: sea, land, and sky/heaven. Later, after the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), other sources more clearly defined the dragon’s attributes, many associated with other animals including the antlers of a stag, the body of a snake, the scales of a carp, and the talons of an eagle. Two millennia later, these characteristics remain relatively unchanged, thus the dragon is an easily recognized motif throughout East Asian art history.

Dragons feature heavily in Chinese stories and mythology and appear in art depicting those stories. This painting by Kanō Tsunenobu 狩野常信 (Japanese, 1636–1713) portrays a story where the Daoist veterinarian Ma Shihuang (or Bashiko in Japanese) treats an ailing dragon. A master horse doctor during the legendary rule of the Yellow Emperor, Ma was reportedly so adept he could accurately predict the lifespan of a horse by just looking at it. In the story, he heals a sick dragon by applying acupuncture to its mouth, which is the moment captured here by Tsunenobu. Ma sits and calmly holds the needle in his right hand while the dragon emerges from dark clouds to be treated.

In Imperial China, dragons were strongly associated with the emperor, a tie that existed since the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE) when emperors were first referred to as the “Son of Heaven.” Due to this association, dragon motifs often appeared in imperial contexts, most notably on clothing created for members of the court. This robe was made for a lower prince of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911) court, indicated by the five-fingered dragon (a motif reserved for the emperor and his closest family) and the blue color. A large dragon is emblazoned across the chest with smaller dragons on the lower left and right as well as on the arms and back. Here the dragon represents the emperor’s authority as the Son of Heaven, as well as the wearer’s proximity to that authority.

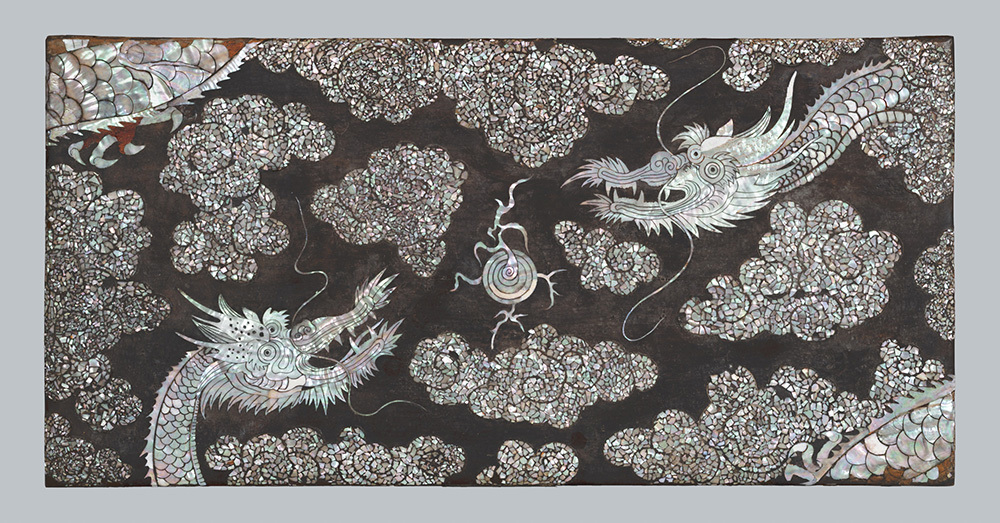

Dragons regularly appear outside the imperial context as potent symbols conveying themes of strength and prosperity. Their auspicious nature lends the dragon to be used as a decorative motif on everything from ceremonial items to daily use objects, such as in this lacquerware chest from Korea. The theme depicted here, Dragons Chasing a Flaming Pearl (shuanglong xizhu 雙龍戲珠), is one of countless traditional designs which center on dragons. This dazzling example features inlaid mother-of-pearl used to create the writhing bodies of the dragons as well as the glittering clouds which surround them.

Chest, late 19th century, Korea, lacquer, wood, mother-of-pearl, and metal, Gift of Walter and Vanida Davison, 2013.118

These three examples, in different mediums from various points of origin, exemplify how widespread the dragon is in East Asian art. Chinese dragons not only represent power and abundance, but also embody over 2,000 years of continuous culture across a whole region of the world. Come by the museum this Year of the Dragon to see for yourself the significance and power of the dragon!

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: