- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

Blog: CAM Uncovered

Blog: CAM Uncovered

- Home

- Plan Your Visit

- Art

-

Events & Programs

- Events & Programs Home

- Calendar

- Accessibility

- Adults

-

Families & Teens

- Families & Teens Home

- 10x10 Teen Art Expo

- Art on the Rise

- Art Together: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 3–5

- Babies Sing with May Festival Minis

- Boy Scouts / Girl Scouts

- CAM Kids Day

- Family Storytime and Gallery Walk

- Family Studio: Art Making for Families with Children Ages 6–12

- Games in the Galleries

- Members-Only Baby Tours

- Public Baby Tours

- REC Reads

- Rosenthal Education Center (REC)

- Saturday Morning Art Class

- See Play Learn Kits

- Summer Camp

- Teen Fest: Zine and Comic Exchange

- RECreate

- Teachers

- Community Outreach

- Fundraisers

- Plan Your Own Event

- Give & Join

- About

- Tickets

- Calendar

- Exhibitions

- Collections

- Blog

- Shop

Looking at Things: Franz Hanfstaengl’s Photographs

by Serena Deng, Photography Collection Research Intern

8/15/2023

photography , Franz Hanfstaengl , intern

In the fairytale Beauty and the Beast, humans are transformed into household objects, then back into humans again. In the movie Night at the Museum, an ancient spell brings museum exhibitions to life at sundown. Without magic spells or CGI, German photographer Franz Hanfstaengl’s pictures of objects feel enchanted, too.

In 1871, the Royal Historical Museum in Dresden (the present-day Green Vault) commissioned Hanfstaengl to document the objects in its collection. Among the 160 photographs produced, lively prints of five found their way to the Cincinnati Art Museum.

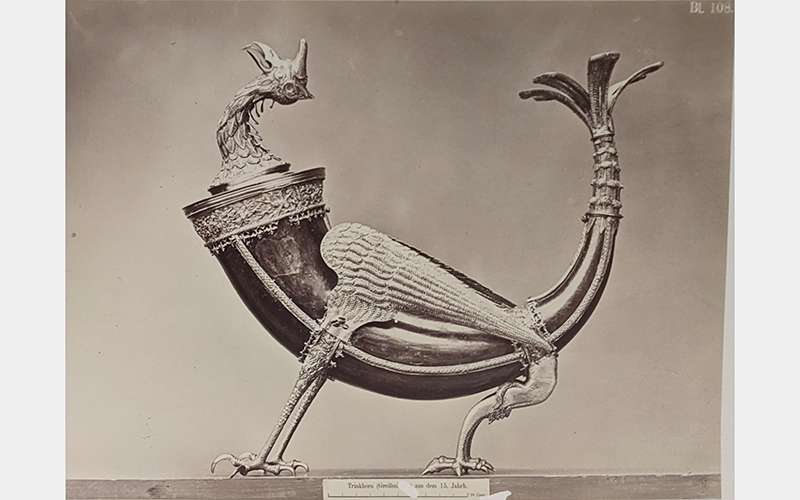

Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Trinkhorn (Drinking Horn), 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum

Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Luthers Trinkgefäss und Trinkgefäss aus dem Anfang der gothischen Kunstepoche (Drinking Vessel of Martin Luther and Early-Gothic Drinking Vessel), 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum

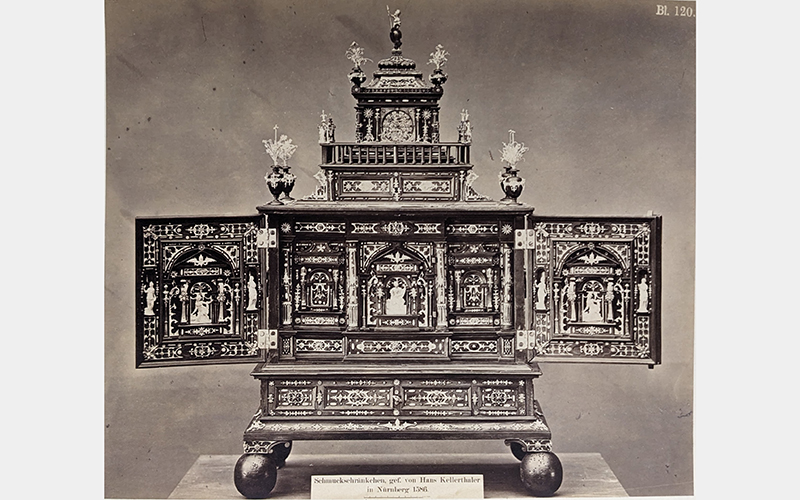

Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Schmuckschränkchen (Jewelry Cabinet), 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum

![Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Pokale (geschnittene Cocosnüsse) aus dem 17. Jahrh [17th-Century Goblets (carved coconuts)], 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum](/media/gfsgq3jt/4-coconut-goblets.jpg)

Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Pokale, geschnittene Cocosnüsse, aus dem 17. Jahrh (17th-century Goblets, carved coconuts), 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum

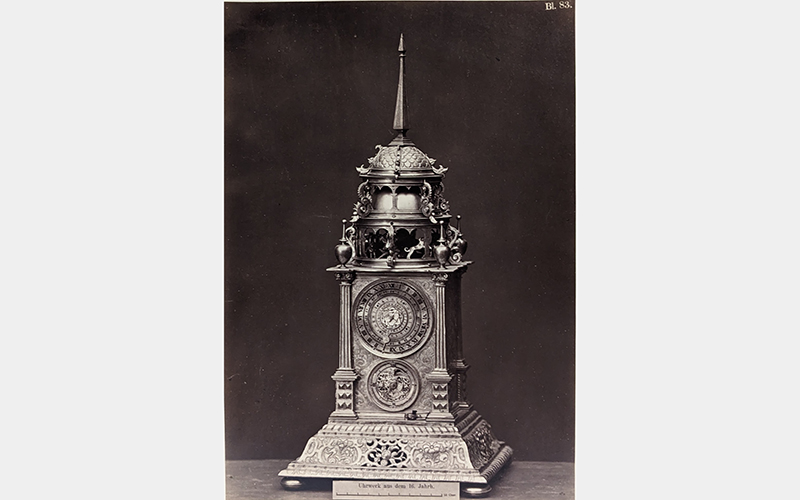

Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl (German, 1804–1877), Uhrwerk aus dem 16. Jahrh (16th-century Clock), 1871, printed 1873, albumen silver print, Property of the Cincinnati Art Museum

A drinking horn decorated to resemble a griffin arches its neck, stretching. Two goblets have been paired together to hold a secret conversation. The doors of a cabinet have been opened, like arms waiting for an embrace. Three drinking vessels carved from coconuts appear lively, standing to attention for their photograph. A clock positioned at an angle and suffering from a slightly crooked spire seems to be tilting its head for the camera.

Born in 1804, Hanfstaengl initially established a lithography business, shifting to photography in September of 1852. Before turning to museum collections, he began his career in photography as a portraitist, notably working for the Bavarian Royal Court. There, he photographed well-known figures such as Otto von Bismarck and Franz Liszt, intending to put together a complete album of the culturally eminent. Though he left his station as court photographer and soon drew commissions from museums, perhaps he didn’t really abandon portrait photography—he just adopted a different sitter.

Hanfstaengl was nearly 70 years old when he arrived at the Royal Historical Museum in Dresden. Still, he spent four wintry months patiently documenting every object in the museum’s collection, bringing each item outdoors to a makeshift rooftop studio so that he would have adequate light for the less sensitive photographic chemistry of the time. When I first came across these photographs, I wondered, what prompted Hanfstaengl to give so much care to these inanimate objects, at the very end of his life? I couldn’t help but imagine him treating them as people, chatting with them, giving them instructions to stand in a certain way. He must have told the goblets a funny joke to prompt one to turn to the other, and corrected the drinking horn’s posture so that it would look perfectly arched. He must have waited patiently behind the camera until each one posed just right.

As instinctive as it may be to personify Hanfstaengl’s objects, the element of fantasy and delightful make-believe I perceived in his photographs initially felt out of place. I often think of museum photography—the pictures of artworks we see on the museum’s website, in books, and in the research files the museum keeps—as empirical, documentary, even scientific. Hanfstaengl was clearly aware that his pictures served those functions, including ruler markings for scale in the bottom foreground of each photograph. At the same time, efforts to record and convey information about an art object are tangled with our innate desire to aestheticize or humanize them. Today, when curators and photographers at CAM discuss documenting its collections—in addition to identifying key physical attributes a picture needs to convey—they may speak of capturing a chair’s best “face,” or imagine how to picture a vase as if it came into the studio on a “good hair day.”

Even in his formal portrait work, Hanfstaengl was sensitive to the power of objects to characterize or stand in for people. His portrait of Louis I of Bavaria, for example, depicts him in uniform, posed carefully with a cane in his left hand and an officer’s hat in his right. The things that clothe and surround the king’s body are what convey his power and status. They pose for the photographer, too.

Instead of flattening the objects from the Royal Historical Museum to literal documentation, Hanfstaengl used photography to preserve and even amplify their specialness, visually cherishing them as he might a person. “Since its invention, photography has become the principal means of working the enchanting transformation when a mere object becomes a thing with a soul,” writes Marina Warner for the Victoria and Albert Museum in Things: A Spectrum of Photography. Hanfstaengl’s camera, then, is the wand that casts the spell of humanity over his objects—it transforms them from objects to be admired into subjects that magically speak to us when we view them. This practice of photographing possessions reveals that our imaginations can’t help but animate the objects around us, wishing for them to be beautiful and breathing things.

Related Blog Posts

Cincinnati, OH 45202

Toll Free: 1 (877) 472-4226

Museum Hours

Museum Shop

Terrace Café

Library

Cincinnati Art Museum is supported by the tens of thousands of people who give generously to the annual ArtsWave Campaign, the region's primary source for arts funding.

Free general admission to the Cincinnati Art Museum is made possible by a gift from the Rosenthal Family Foundation. Exhibition pricing may vary. Parking at the Cincinnati Art Museum is free.

Generous support for our extended Thursday hours is provided by Art Bridges Foundation’s Access for All program.

General operating support provided by: